Why AP African American Studies Will Not be Taught at Latin

The College Board’s newest course, AP African American Studies, was recently evaluated and changed because it is considered to be “woke indoctrination.”

The College Board currently offers 38 Advanced Placement courses with varying options spanning from Art History to Physics C: Electricity and Magnetism. Such courses offer the opportunity for students to take on academic challenges in high school and potentially earn college credit. AP classes contain the same content universally, so as to prepare students for a final exam at the end of the year.

AP African American Studies is the newest course in the AP catalog. Over the past two years, the College Board has worked to develop and structure the course, piloting it in 60 schools during the 2022-23 school year. But just as it made its way into classrooms, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis set the process back after speaking out against the course, claiming it was an instance of “woke indoctrination.” Since then, topics such as critical race theory, black feminism, and queerness have been removed from the curriculum, and “black conservatism” has been added.

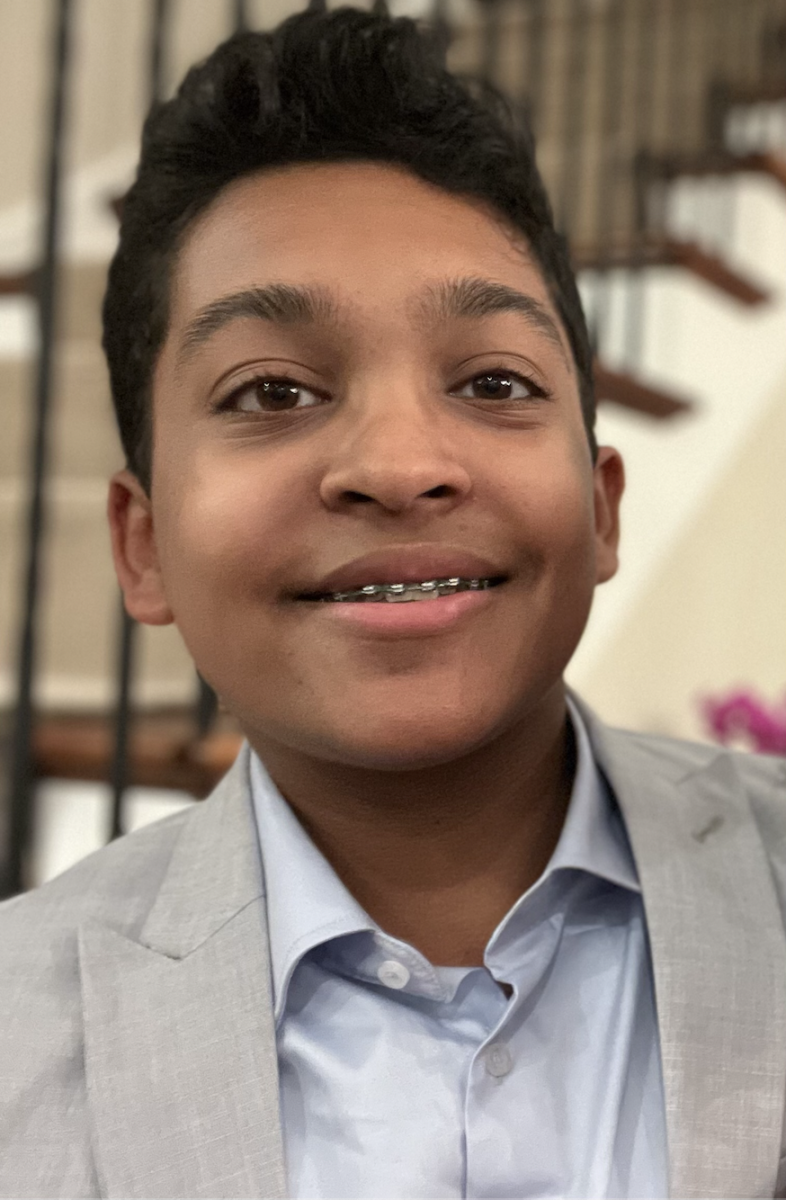

Upper School English teacher and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Curriculum Coordinator Brandon Woods said, “[Woke indoctrination] is a really powerful word to use. And as a teacher, it’s really offensive, because what they’re saying is that we’re trying to indoctrinate our students into a certain ideology, which just shows he’s not a teacher, and shows how little respect he has for teenagers. If he thinks all we have to do is stand up in front of teenagers and tell them what to think, he has no idea what teaching is.”

Upper School history teacher Lucie Wright emphasized the importance of looking at the broader context around DeSantis’ concerns about AP African American Studies. Ms. L said, “I think this idea of woke indoctrination—there’s a few underlying assumptions there that I think are worth making visible. The assumption that there is such a thing as a neutral history class or that to even talk about race, gender, sexual orientation, that to name those things that are important in our world today, is somehow a form of indoctrination. I think it is worth naming and challenging.”

Over the summer, Florida passed the Parental Rights in Education bill, allowing parents substantial control over what their children learn, rather than schools or the College Board. With this law in place, it is difficult to teach some of the topics covered in the curriculum, not only on a state level, but on a national level. Because each course has one specific exam, the curriculum has to be taught uniformly, and if one state demands change, the rest may have to follow.

As for the backlash toward the course as a whole, junior Nadia Rivera said, “I am not shocked that it’s happening. It’s predictable. If you look at the history that prefaces things like this, because you had the Daughters of the Confederacy after the Civil War, where a lot of the Southern states were revamping their curriculum and rebuilding their education system. Those four women completely changed the entire education of the Civil War and demonized the North and made slavery a picnic. And that’s not what happened. So I mean, I’m not shocked, but it’s still disappointing.”

Next year, Latin will not be offering AP African American Studies, and given the lack of AP courses in Latin’s curriculum, it’s no surprise. Currently, Latin offers seven APs, all in STEM and language fields. Advanced Topics classes are also available, and they follow that rigorous curriculum without necessarily being tied to a textbook or set syllabus.

For many American high schools, the College Board defines rigor. For some schools, it can be incredibly useful, but at Latin—a school with so many internal resources and a reputation of being generally rigorous—the implementation of the College Board’s input into the curriculum isn’t as important. In fact, Latin has actually taken strides to move away from AP curriculum in some subject areas.

Prior to teaching at Latin, Upper School History Department Chair Ernesto Cruz taught AP European History for years in public schools. He said, “At that time, in that place, at that school, they needed an outside group to come and say, ‘This is what hard is, this is what challenging is.’ Because community standards and expectations around education were low, and so having an independent organization come in and say this is where the bar is [was] a useful thing. Latin doesn’t need that bar.”

While Latin is not planning to offer the course next year and does not necessarily have a parallel, non-AP course, there are other offerings that discuss marginalized identities as a whole, rather than looking at just one like the AP African American Studies class does.

Mr. Woods said he believes that every identity is worthy of discussion and that it is essential not to form a “hierarchy” of which identities are most “important” to teach. He said that the sophomore history elective “What is Race” sets a solid foundation for that approach. “It doesn’t just focus on the black-and-white dichotomy that is often the story of race in America. But how has this fiction of race been invented? And then how does it affect all of us? Everyone’s a part of that conversation because everyone is influenced by this.”

“What is Race” is not taught chronologically, but rather as an evolving course that adapts to current events and considers how certain history is taught. Ms. L, who taught the course last year, said, “It’s one of those subjects where you are not outside of the consequences of the history you are studying. I think students learn both to think about how you learn about race, how you think about the historical construction, and what that means in the present. We might one day be studying 1600s colonial Virginia, and the next day we are studying something that happened here in Chicago.”

Sophomore Finn Deeney, who took “What is Race” first semester, said, “I think that it is such an important class because it looks a lot deeper into the topics of racism that we study in other classes as well as giving students a deeper understanding of how the world functions around us, however uncomfortable that is. These classes that teach topics like Critical Race Theory give students an unfiltered look at how race and racism are ingrained in our lives, something that I don’t think a lot of other schools offer.”

Similar to Mr. Woods, Nadia said she feels that classes should not always hone in on one specific identity, but she noted the value of such a course. She said, “There are some Black Americans that just don’t know that history, and to open the door to people who want to learn about African American history without having to talk about the 20 other things that went into that history is a lot sometimes. It’s cool to have both of those offered based on what somebody would want to learn.”

Additionally, the History Department has developed a new tenth-grade elective for next year, “Exploring the Communities & Cultures of the African Diaspora,” which will lead discussions about race in Europe and Latin America.

As of now, the content of the AP African American Studies curriculum will continue to undergo discussion nationwide, but its representation of a history typically less taught is promising for many. Nadia said, “We want better people. We just want to have children in our society grow up to be better than the last. We just need to do better.”

Eliza Lampert (’24) is a senior at Latin and is overjoyed to serve as one of this year’s Editors-in-Chief. During her time writing for The Forum, she...

Ms. Linder • Apr 5, 2023 at 8:27 pm

Great job with this, Eliza.

David Marshall • Mar 28, 2023 at 8:28 am

Great article—so thoughtful! Thanks!