Reviewing Latin’s Concussion Protocols

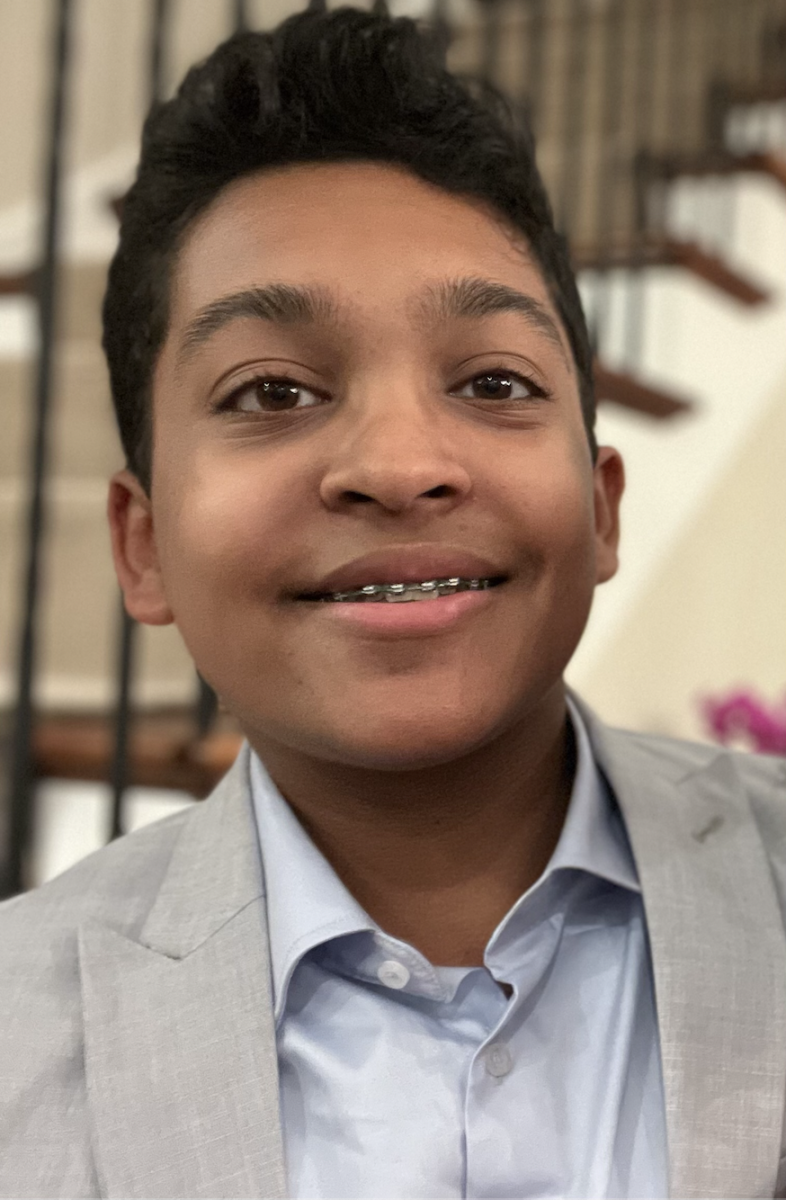

Collin Dwyer ’22 seen battling for a faceoff in a lacrosse game

An influx of severe head injuries afflicting NFL players has caused the Latin community to reflect on its own concussion protocols. During a Thursday Night Football game on September 29, Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa was rushed to the hospital after his second concussion in less than a week, worrying many NFL fans.

In another game on the Sunday prior to Tagovailoa’s hospitalization, he struggled to walk after being driven to the ground by Bills’ linebacker Matt Milano. Despite his evident instability, Dolphins coaches and independent consultants (who have since been fired) cleared Tagovailoa to return to the game and play just four days later in Cincinnati. After being sacked hard once again by Bengals’ lineman Josh Tupou, Tagovailoa experienced fencing, an uncontrolled response to a concussion where one’s forearms are flexed or extended into the air for several seconds. He lay seemingly lifeless on the field for minutes before being carted off the field on a stretcher. Thankfully, doctors found no permanent damage to Tagovailoa’s brain, and he was released from the hospital later that evening.

Since then, other NFL players have also suffered severe head injuries. Senior Luca Tricoci said, “What’s happening to these players is scary.” He added, “I know it’s been going on for quite a long time, but seeing what happened to Tua, Bridgewater, Hines, and Savion Smith, who was knocked unconscious and taken off the field in an ambulance last Sunday, is really eye-opening.”

While the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) has waged war on the league’s concussion protocols, all athletes are concerned about their safety during contact sports. Although Latin does not field a football team, student-athletes have experienced severe concussions in basketball, soccer, and hockey, among other sports.

Senior Megen Sanaj said, “I hit my head on the ground playing basketball and blacked out for a few seconds.” She continued, “Being eager to play again made me a bit mad, but Latin did follow procedure, and for a week, I had to gradually work my way back to full contact.”

Other student athletes expressed similar sentiments as Megen when reliving their concussion experiences at Latin.

Junior Reeise Remmer said, “After I met with [Latin athletic trainer] Jessie [Heider] and I went to the doctor, they handled protocols effectively for me to return.” The soccer star added, “I wasn’t happy that I was out, but at the same time, it made sense.”

All Latin students must take a concussion baseline test every other year to determine how quickly and accurately they can complete a set of questions when healthy. If a student experiences a head injury, they must retake the test to determine if their cognitive functions are altered.

“I developed Latin’s Sport Concussion Policy and Protocol for Student-Athletes with the help of Athletico several years ago,” Ms. Heider said. “Latin also formed a Concussion Task Force in 2016, and this group was tasked with developing Latin’s Concussion Return to Learn Policy and Academic Concussion Management Plan. I don’t believe there were any policies in place prior to my time at Latin.” According to Ms. Heider, the IHSA has also implemented regulations regarding athletic department concussion policies.

Although students expressed positive reviews regarding Latin’s overall concussion protocols, not everyone believes in the effectiveness of the baseline test. Senior Alice Mihas, who was struck in the head while doing judo as a freshman but was not diagnosed with a concussion, said, “I feel like the baseline test was so hard that the difference in results between before and after my head injury wasn’t substantial.”

Additionally, multiple students said they knew of peers either faking their baselines so they could return to play if they ever experienced a head injury, or forcing other students to do their baseline for them. In either of these cases, the concussion baseline test would be rendered ineffective.

Senior Anton Schuster said, “When I was a freshman, I knew seniors on the water polo team who persuaded underclassmen to do their baselines for them.” He added, “I don’t know why anyone would want that; the baseline is for your own safety.”

Conversely, some students have refuted the idea that it is even possible to fail the test on purpose.

Junior Spencer Webster insisted there was no way to flunk the baseline, except by accident. “I have done the baseline in consecutive years,” he said, “and it is very hard to fake, because you actually need to focus since it’s a very difficult test.”

While Latin students feel secure with their school’s handling of concussions and can take steps to ensure their own safety by doing the baseline as directed, the well-being of professional athletes still hangs in the balance. Although the NFLPA did approve updated protocols on October 7, teams will inevitably keep their best players on the field, even if concussed. Winning has been, and will undoubtedly continue to be, prioritized over player safety.

Many in the Latin community are reluctant to believe that the NFL has handled concussion protocols correctly this season and are pessimistic regarding their favorite athletes’ safety going forward. Latin School Nurse Erin Crowley bluntly addressed her disappointment in the NFL’s player safety policies. “I am inclined to believe that they need to have a much more conservative approach when determining if a player can return to participation following a head injury or concussion,” she said.