The Hollywood Writers Strike Plans To Take Down More Than Just SNL

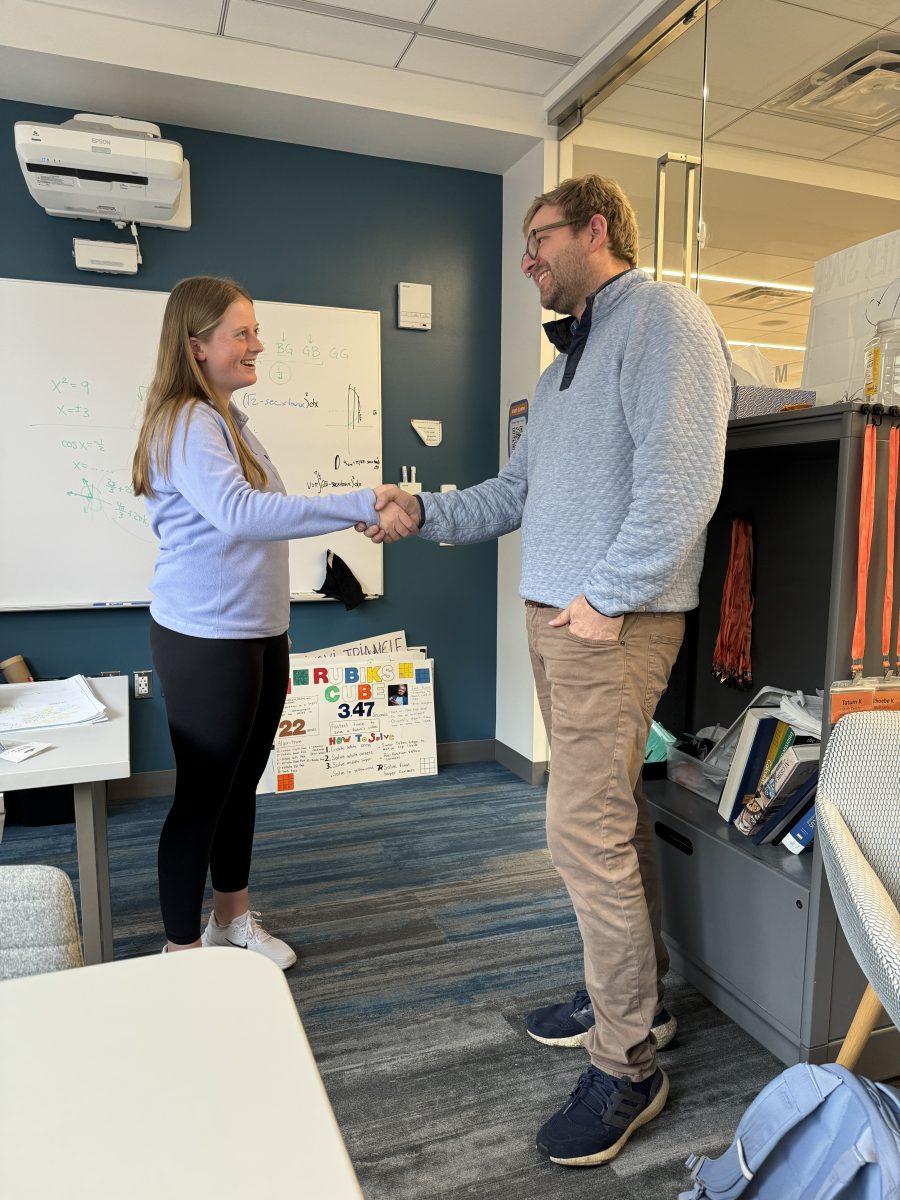

Creative Commons Wikimedia

Hollywood writers strike on the famous Avenue of the Stars, fighting for more pay and more recognition.

“Money makes the world go round” is an age-old saying that has stood the test of time simply because of its truth. A prime example of this statement in action is the current Writers Guild of America (WGA) Hollywood writers strike, where over 11,500 writers have banded together to protest the subpar conditions Hollywood has put them under following the advent of streaming services.

Anticipated back in February, the entirety of WGA finally united and began their strike three minutes after their previous contract expired at 12:01 a.m. on May 2. This was all in an effort to escape their current economic situation in which writers are split into “mini-rooms” and forced to do the same amount of work in smaller groups with no long-term financial gain.

Thus, late-night shows, including The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, Late Night with Seth Meyers, Last Week with John Oliver, Real Time with Bill Maher, and Saturday Night Live, will not air until the strike concludes.

Additionally, any motion pictures, television, cable, digital media, and radio/audio entertainment currently in the script-writing phase will be put on indefinite hold. Freshman Jack Zeiger said, “I’m really sad I can’t watch SNL. I watch it all the time with my family, and it is a tradition that my old advisory would watch it.”

As streaming services and shows skyrocket in popularity, established studios like Netflix, Amazon, Apple, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, NBC Universal, Paramount, Comcast, and Sony—all under the umbrella of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), which represents over 350 American film and television companies—have used the transition from cable television to streaming services as a scapegoat to cut writers’ salaries and separate them for production by cornering writers into “mini-rooms” where they break down plotlines, develop character arcs, and create outlines. This is an arrangement where writers are paid the union minimum, not the typical long-term monthly payments with residuals once the show is done airing. These recent changes have left writers unable to make a living off of the same job some had been doing for decades.

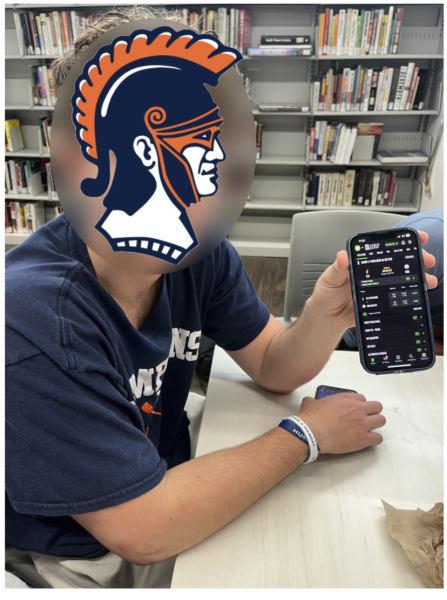

A screenwriter’s job is to write an outline, then the first draft, and any more drafts that follow, with the outline being paid separately from the drafts. With Artificial Intelligence (AI) already having such a powerful surge of influence over society, WGA strikers are concerned about a future when their job is meaningless thanks to a computer that can generate outlines and drafts to any given studio head’s liking.

Upper School English teacher James Joyce said, “I think the benefit of a human writer is the idiosyncrasies, or the unique, weird characteristics that individuals have. I’d imagine those are probably difficult to replicate with the computer, but maybe not impossible. Maybe human-written content will be kind of like boutique or gourmet dining.”

Possibly the biggest driving factor for this strike is the shrinking residuals offered by such noteworthy companies. Residuals are continuous payments awarded to both in-front-of and behind-the-camera talent as the program airs on DVD, Blu-ray, cable, Tubi, YouTube, and so on. Famous sitcom actors such as Jerry Seinfeld or Jennifer Aniston have made tens of millions of dollars off of residuals, and many up-and-coming talents rely on these payments to survive. According to the WGA, median writer-producer residual pay has declined by 23 percent, adjusting for inflation, as streaming services are far more likely to order a 10-episode season than cable networks’ previous 22-episode seasons.

If shows are cut in half, residuals are cut, too. The reason that so many beloved shows are leaving Netflix is often that Netflix executives didn’t want to be responsible for paying the costly residuals to the talent involved.

But this strike isn’t the first of its kind. Back in November 2007, the entirety of the WGA went on strike, demanding increased funding from the AMPTP. In just 100 days, this strike ended up costing the studios $2 billion. The strike affected actors like Daniel Craig, who was deep into production when he was suddenly left with no writers and had to do significant rewrites himself on an already half-baked script, which many blame for the demise of Quantum of Solace. In the end, WGA writers were awarded a 2% increase in residual payments.

Junior Joanna Nar feels empowered by the WGA’s advocacy. “I think everybody obviously deserves to be paid equally, and I hope this strike will accomplish that goal.”

The idea that everyone who works in Hollywood lives some overly indulgent lifestyle is a fantasy. In fact, only two percent of the most reputable actors’ union, Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), do not have to work two jobs to sustain being an actor.

According to a tweet by a WGA writer, the average staff writer makes $45,000 for a nine-week gig. Subtract 20 percent for agents and managers, 1.5 percent for WGA dues, and maybe 20 percent for taxes, and then consider how expensive it is to live in Los Angeles and also that it could take up to 12 months until one’s next job offer.

Currently, the WGA writers stand in solidarity outside 10 Hollywood studios, marching for up to eight hours with signs reading, “Writers Guild of America,” and below it a blank white space for the writers to fill in with messages to the studios they surround. Some of these messages include, “We came here to live the dream, not to lose it to the stream!” “Here’s a pitch: pay us!” “Alexa will not replace us!” and “Writers make studios rich—studios make writers strike!”

These writers are asking for money and respect from the very movie studio executives for whom they have provided a surplus of content for decades simply so they can make a sustainable living. Leaving the movie theater, audiences remember the lead actor, often the director, maybe a producer, but rarely the writer. Now perhaps they will.

Mr. Joyce said, “It’s a ‘you get what you pay for’ situation for the movie studios.”

Ignatius Doherty ('26) is a freshman and is honored to be joining The Forum staff this year. Having a lifelong interest in writing, he plans to bring a...