Claes Oldenburg’s Larger Than Life Legacy

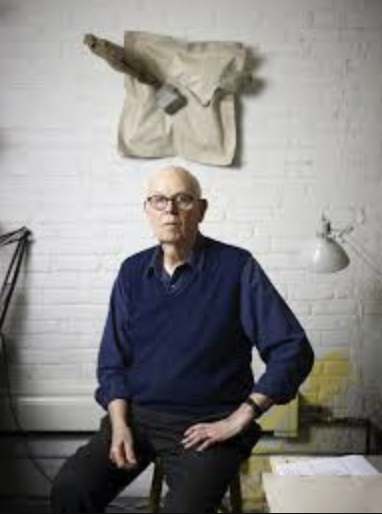

With Homecoming weekend fast approaching, the Latin community is preparing to welcome alumni for reunions to celebrate their successes and memories. Homecoming is also a time to honor members of the Latin community who passed away in the past year. Legendary pop art artist and sculptor Claes Oldenburg ‘46, who died in July at age 93, will be commemorated during Homecoming weekend this year.

Oldenburg is known for his giant sized public art and sculptures of everyday objects. Giant may not be a big enough adjective—his art was supersized.

“Claes’ work was a monumental achievement when it comes to scale, innovation, design, and longevity,” Middle School art teacher Russell Harris said. “Being a graduate at Latin School is a great way for him to be an inspiration to up-and-coming artists to let them know that being an artist is more doable than they think if they have the drive, the perseverance, and the voice to share their imagination with others.”

Oldenburg enrolled at Latin at the age of seven when his family moved to Chicago so his father could serve as the Swedish Consul General. After graduating from Latin, he studied at Yale University, and after college, he returned to Chicago to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). While at SAIC, he worked drawing comics for the Chicago City News Bureau. But comics would not be where he made his name—supersized sculptures would become his signature.

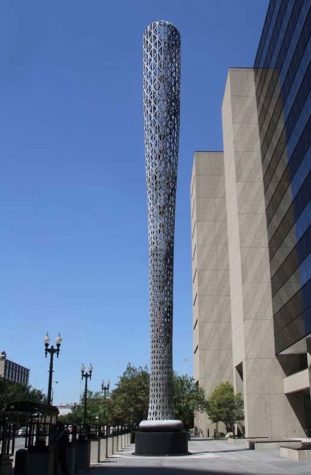

His work is on display across the world, from Tokyo to Minneapolis. In 1977, Chicago received its own Oldenburg sculpture. His work in Chicago, known as “Batcolumn,” is 101 feet tall. Located at 600 West Madison, it is a colossal gray metal baseball bat, made of steel lattice, and it looks like it might belong in the city skyline. The “Batcolumn” is true to Oldenburg’s signature style: taking an everyday object and expanding it to gargantuan proportions. According to the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, “[The ‘Batcolumn’] can alternately be seen as a reference to historical monumental columns, a salute to the American institution of baseball or a tribute to the steel industry.”

Today, 45 years after its installation, it can be seen as part of the city. The sculpture is perfect for a two-baseball-team town. It also is perfect for a town where public art is valued, from the Picasso sculpture to the Bean. A plaque at the base of the “Batcolumn” reads, “Oldenburg selected the baseball bat as an emblem of Chicago’s ambition and vigor.”

However, one sculpture that Oldenburg planned never came to fruition. A decade before “Batcolumn,” in 1967, he proposed replacing another well-renowned, giant monument—the Washington monument—with a giant sculpture of open scissors. “Scissors in Motion,” the considered name of the sculpture, seems especially relevant today as it was a way to symbolize a divided country. America still has a passion for baseball and is still wrestling with bitter divides and polarization. Oldenburg had a passion for capturing these large issues and portraying them in a larger than life way.

In the Lower School, art teacher Brenda Friedman, who recently retired from Latin, taught her classes about Claes Oldenburg and how everyday objects are art and inspire art.

Latin senior Cole Hanover fondly remembers the lesson on Oldenberg. “I remember learning about Oldenburg in Lower School as part of Ms. Friedman’s unit on contemporary artists, and the sculpture that caught my attention most was a photo of the spoon with the cherry on it, just because it looked stylish,” Cole said. “It wasn’t until I visited the sculpture garden in Minneapolis this summer that I got to see it in person and truly appreciate the design, stature, and infrastructure of the piece. It’s truly something to behold. It’s a shame I didn’t take the time to recognize the ingenuity that went into his work until after he passed.”

Upper School art teacher Derek Haverland also expressed his admiration. “One thing I appreciate about Oldenburg is the way he took everyday objects that would fit in your hand, and exaggerated the scale into something excessive, monumental, or larger than life,” Mr. Haverland said. “While some maintain the form of the actual object, other ‘soft sculptures’ create an unusual twist on how we normally perceive everyday objects.”

Claes Oldenburg’s legacy—much like his art—is huge. He thought big and made big things. That he began his education and career right here at Latin is a great source of Roman pride.

Matthew Kotcher ('23) is thrilled to continue to serve on The Forum as the Arts Editor and now as Director of Staff Recruitment and Development. Matthew,...