Latin Students Respond to Ethics of Brandon Bernard Case

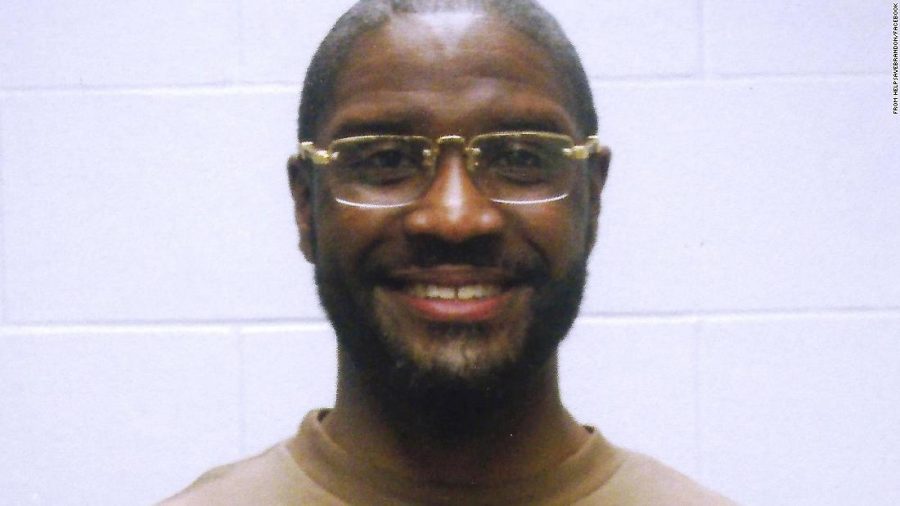

Brandon Bernard

Brandon Bernard, a 40-year-old Texan, was executed on December 10 in Terre Haute, Indiana by lethal injection on behalf of the United States federal government. Bernard was sentenced to death in 1999, when he was 18, stemming from his involvement in the murder of Todd and Stacie Bagley.

Angela Moore, a former federal prosecutor who fought to put Brandon Bernard on death row, later spoke out against his sentence, saying that he did not have the “capacity to control his impulses, consider alternative courses of action, or anticipate the consequences of his behavior” at that age. His last words lasted more than three minutes, including, “I wish I could take it all back, but I can’t.” About 20 minutes after the first injection, Brandon Bernard passed away at 9:27 pm.

Bernard’s death was the first lame duck execution (signed off on by a president who has been voted out of office) since 1890, when Grover Cleveland was president. Before Bernard’s execution, a petition to commute his death sentence accumulated more than 500,000 signatures, causing widespread outrage over social media, and fanning the red-hot flames of the death penalty debate.

The execution stirred Latin students, who seem to overwhelmingly disapprove of the death penalty’s role in the justice system.

Senior Maeve Healy said, “According to the Eighth Amendment, Americans should not be subject to cruel and unusual punishment, and the death penalty qualifies as both.”

The U.S. Supreme Court declared the death penalty to be unconstitutional in 1972, arguing that capital punishment violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Beyond the moral conflict of taking someone’s life, there are plenty of other issues with the practice. Many studies have found that the death penalty does not deter crime, and it is much more expensive than life without parole. Moreover, the most commonly practiced method of execution, lethal injection, is far from a painless poison, causing a severe, burning sensation, simulating drowning.

In 1976, four years after the Supreme Court had halted capital punishment, the Court changed its mind, holding that “the punishment of death does not invariably violate the Constitution.”

Maeve offered another argument against capital punishment—the fact that innocent defendants are sometimes convicted and sentenced to death. “A significant number of people who have been sentenced to death row have later been proven to be innocent,” she said. On the national level, for every 10 people executed on death row, at least one is exonerated. Since 1976, the U.S. government has executed 13 people: three under the George W. Bush administration, and 10 under the Trump administration.

Most executions occur under the laws of individual states, not under federal law. In the United States overall, a staggering 1,529 executions have occurred since 1976.

Freddi Mitchell, a senior, said, “I think that the government shouldn’t kill its citizens. Killing is not a punishment; It’s inhumane.” The word “inhumane” appears to be closely tied to criticisms of the death penalty, as three of the eight students interviewed used it to describe the punishment.

Eliana Moreno, a junior, agreed that the word applies. “I think the death penalty is outdated and should be abolished, because death is never the right punishment for anyone. It’s inhumane.”

Brett Lasky, a junior, said, “I believe capital punishment is wrong and inhumane. The ruling to take Brandon Bernard’s life is a tragedy and is another example of the justice system failing the black community.” As is always the case with issues within the criminal justice system, race and discrimination are exceedingly relevant to the discussion surrounding capital punishment.

Junior Kazi Stanton-Thomas said, “The death penalty is just another tool used by this faulty justice system. With the ideology of punishment instead of rehabilitation that comes with the U.S. prison system, the death penalty is held to be the ultimate punishment.”

Bernard’s execution begs the question: What is the ultimate goal of incarceration? Criminal disenfranchisement, the death penalty, and for-profit prisons all suggest that the U.S. justice system does not prioritize rehabilitation. Rather, it values retribution that achieves the government’s financial and political goals.

Kazi continued, “The death penalty is served to BIPOC individuals way more often than white individuals (even if said white individuals have committed far worse crimes). So, in a way, the death penalty is an evolution of cultural culling seen in US history for centuries.” The death row population in April of 2020 was 41.38% Black, 13.52% Latinx, 42.22% white, and 2.88% other racial/ethnic identities. In the U.S., Black people make up less than 15% of the total population.

Anaitzel Franco, a sophomore, added, “As a child, I felt like I was shown that people who harm others should be harmed. Obviously, now old enough to form an opinion, the government shouldn’t have the power to take away someone’s life. Considering how the death penalty is disproportionately used on BIPOC communities, the power dynamics between the two just seem like another way to reinforce privilege.”

Quin Kies, a senior at Latin, elaborated on this idea, saying, “Capital punishment is disproportionately carried out against minority populations, does not deter further crimes, and far too often lacks the evidential backing.”

This is where the lines, according to Latin students, become blurry. Some, like Kazi, believe that no institution should have the power to decide who is or is not “worthy of further existence,” arguing that it “goes far beyond the realm of moral equality.” Others, like Quin, believe that certain crimes warrant harsher punishment in order to maintain public safety. “The crimes of espionage, treason, and terrorism should be addressed on different moral grounds, as the offenses are more so a matter of ensuring National Security than administering criminal justice, and capital punishment for those crimes, given 100% certainty of the defendants involvement, is justified,” he said.

Becca Wanger, a senior, noted that the question of who lives or dies is impossible to answer unambiguously. “It’s not something that you can answer with logic,” she said. “There’s an irony and absurdity in trying to apply logic to very complex human events. Like, if you rob a store, that’s pretty clear, but you can’t apply a structure to who deserves to die and who deserves to live, because we were all put on this Earth at random.”

Brandon Bernard’s case was the ninth federal execution of 2020. The tenth occurred on December 11, and there are still more federal executions planned before Biden enters the Oval Office. This seems a fair moment to ask: is killing, under any circumstances, humane?

Angela Gil (’21) is a senior at Latin and is honored to be serving as The Forum’s Features Editor. She has written for The Forum...