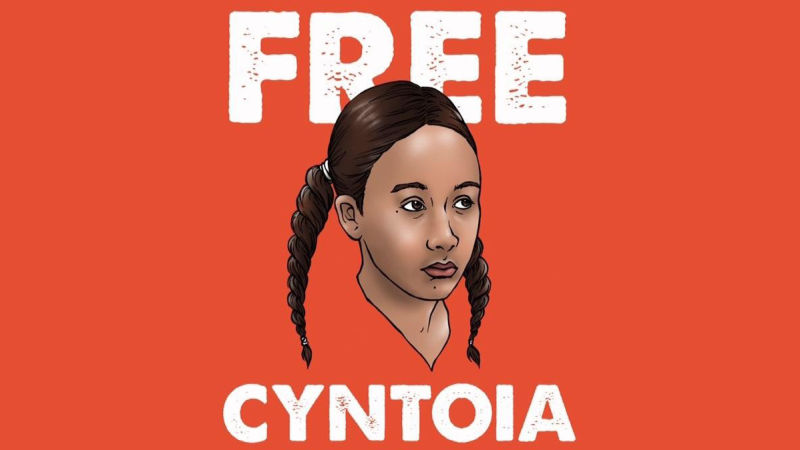

More Than A Hashtag: #FREECYNTOIABROWN

February 2, 2019

On January 7, 2019, Cyntoia Brown was granted clemency after serving 15 years of a life sentence for killing her sex trafficker at the age of 16. She is scheduled to be released from prison on August 7, 2019. Prior to this event, Brown and her legal team unsuccessfully challenged her life sentence, noting the 2012 ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court stating that giving juveniles life sentences without parole was “cruel and unusual punishment” in most cases. After the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled she would only be eligible for parole after serving 51 years, public outrage ensued and the hashtag, #FREECYNTOIABROWN, rapidly spread across social media. For many Americans, Cyntoia’s case not only marks the beginning of necessary reform in the criminal justice system but exists as evidence of the effectiveness of social media activism.

While this conclusion is in many ways true, misconceptions about what it means to be granted clemency and the role of social media in Brown’s case has left many Americans with a bloated image of their role in Brown’s release. While social media increased the case’s volume on the national stage—attracting name-brand celebrities such as Kim Kardashian and Rihanna—posting a picture on Facebook or Tweeting #FREECYNTOIABROWN did little to permeate the judicial bubble where the case resided. Contrary to popular belief, it was not the Tennessee Supreme Court that granted Brown clemency—such an act is not within their jurisdiction. Rather it was Tennessee governor, Bill Haslam, who ultimately made the decision. The court’s ruling was and remains a life sentence. Furthermore, clemency does not mean freedom. The kind of clemency Brown was granted was a commutation. This form of clemency entails that her sentence will be reduced (which it has been), but the conviction is not erased and felony restrictions still apply. She will be under supervised parole for a decade and has to complete 50 hours of community service.

And while public outcry did play a factor in Haslam’s decision, the governor was under immense amounts of pressure from other Tennessee legislators, lobbyist, and full-time activists. Brown’s social media support was an important—arguably essential—factor in her release, but it’s a stretch to say that every person who took five minutes out of their day to post a picture of her with a hashtag played a crucial role.

The reason why efforts to promote justice usually start and end on social media is that many Americans are convinced that activism requires a grandiose, time-consuming gesture. This belief is far from new. For the past few decades, many have felt that unless one planned to attend a three-hour long march, stage a sit-in, or spend a night picketing at the front door of their local legislator, there was nothing they could do to incite change. So when social media activism was introduced in the late 2010s, many saw it as a less preoccupying alternative to traditional protesting, especially young students who often do not have the agency to commit to frequent demonstrations. Unfortunately, over the years social media has become the only platform for protest for many Americans. And while one can argue that the social justice and equity revolution is larger than it ever has been, it is also far weaker.

This fact makes sense. While everyone should take the opportunity to demonstrate their frustration with social and political issues, it’s absurd to expect anyone who’s ever posted a hashtag to have the time, energy, or devotion to be a full-time activist. But perhaps such commitment isn’t necessary. There are countless ways and opportunities to promote social causes without making it one’s profession. Calling local legislators and expressing concerns, volunteering at organizations promoting social causes and outreach programs, donating to those organizations, and—perhaps the most important of all—being an ally for marginalized people are just a few of the ways one can get involved in the movement. And yes, spreading the word through social media.

One can never be sure that the popularity of #FREECYNTOIABROWN isn’t the sole reason Brown was released. But the court’s decision makes it clear that there are serious issues in the criminal justice system and there are countless more like Cyntoia Brown who may never be freed. On January 7, Americans saw what they could do when they unite on social media platforms. Only the future can tell what Americans can do if they take the step—as small as it may be—forward and become the action in activism. The only thing that’s for sure is that the revolution is much more than a hashtag. **

lcampbel • Feb 3, 2019 at 6:21 pm

Your articles never fail to amaze me, Robert. Thank you for digging into this issue and breaking down both its social and judicial complexities. I don’t think many people, including myself, knew the strenuous appeal process it took to have the case heard again. Thank you for bringing attention to such an important moment in our history. The fight, however, is not over. Clemency is a step in the right direction but doesn’t mean our justice system isn’t stil corrupt and defunct. Hopefully, Brown’s case sets forth some precedent that will protect others when they retaliate against their abusers.

nduarte • Feb 3, 2019 at 5:42 pm

Careful with the word revolution the government might hear you

obaker • Feb 3, 2019 at 3:38 pm

Robert, this is so important. You’re right — activism goes beyond using a hashtag. It’s consistently amplifying, listening, speaking up, and questioning the status quo. Thank you for writing this.

tvadali • Feb 2, 2019 at 4:42 pm

Robert,

This is a wonderfully written piece that addresses many of the concerns I had about social media activism. The Cyntoia Brown case is a tragedy in all aspects, but I think you have covered it beautifully. Such great work!

– Tejas V.