Midterm Mayhem

Pixaby

The Upper School administration decided to shorten midterm testing by two days, leaving students and faculty with a range of sentiments about the change.

For decades, the Upper School has used the final academic week of the first semester to administer midterm testing. However, this year, amid an ever-evolving world of education, Latin chose a different route.

“The schedule simply stopped making sense,” 11th and 12th Grade Dean Amy Merrell said.

Latin opted to depart from its previous week-long midterm schedule and adopt a more concentrated and efficient approach—a three-day midterm testing timetable.

Bridget Hennessy, 9th and 10th Grade Dean, explained that the Upper School administration “wanted as much class time as possible because the semester is so short,” and, as a result, discovered an addition of two regular class days could resolve this issue.

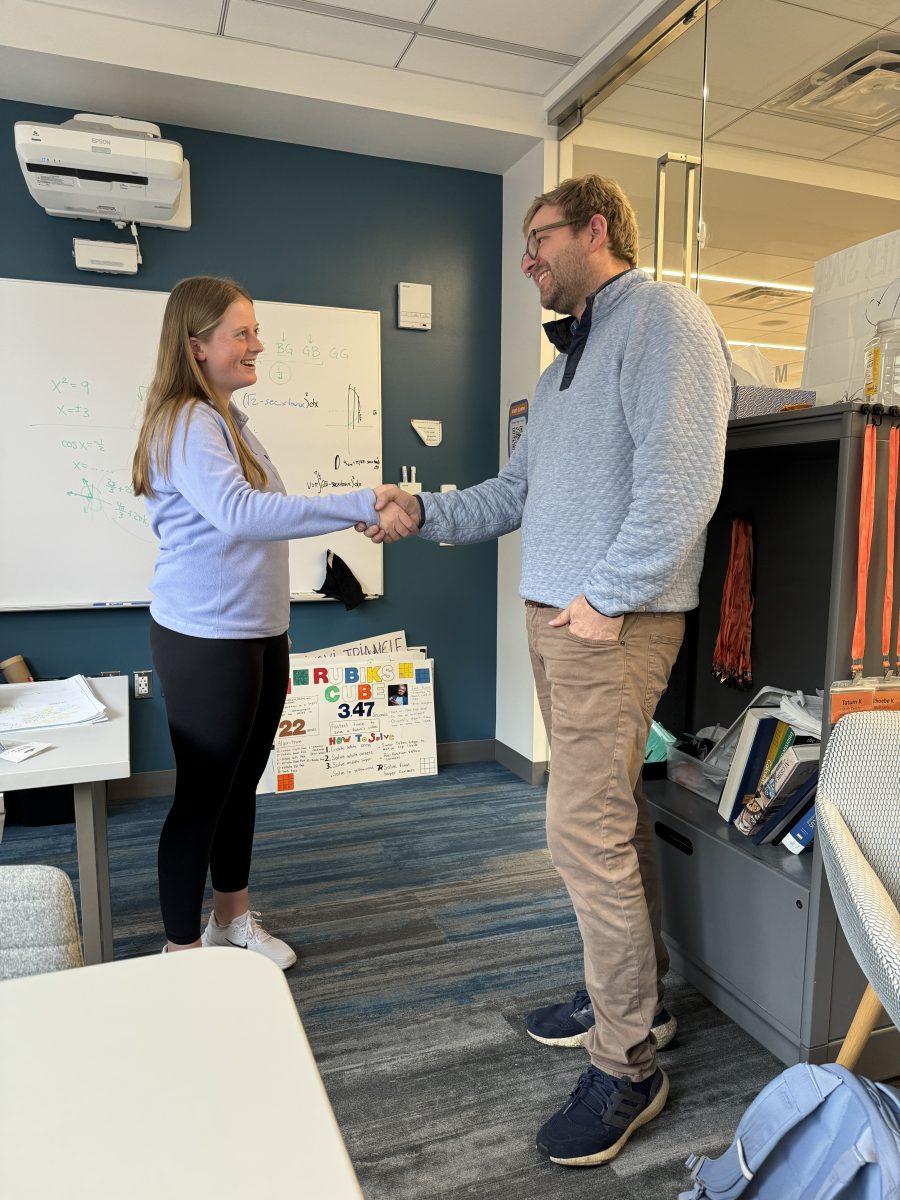

The decision aligns with feedback from Upper School teachers, who communicated that “[their] consensus was that the week-long schedule was really long,” Upper School math teacher Laura Ilkchi said. “Adding those learning days and having class Monday and Tuesday—gaining that time back—was really valuable.”

Rather than teaching new material, these extra class days primarily allowed teachers to provide additional time for review and reflection before final exams.

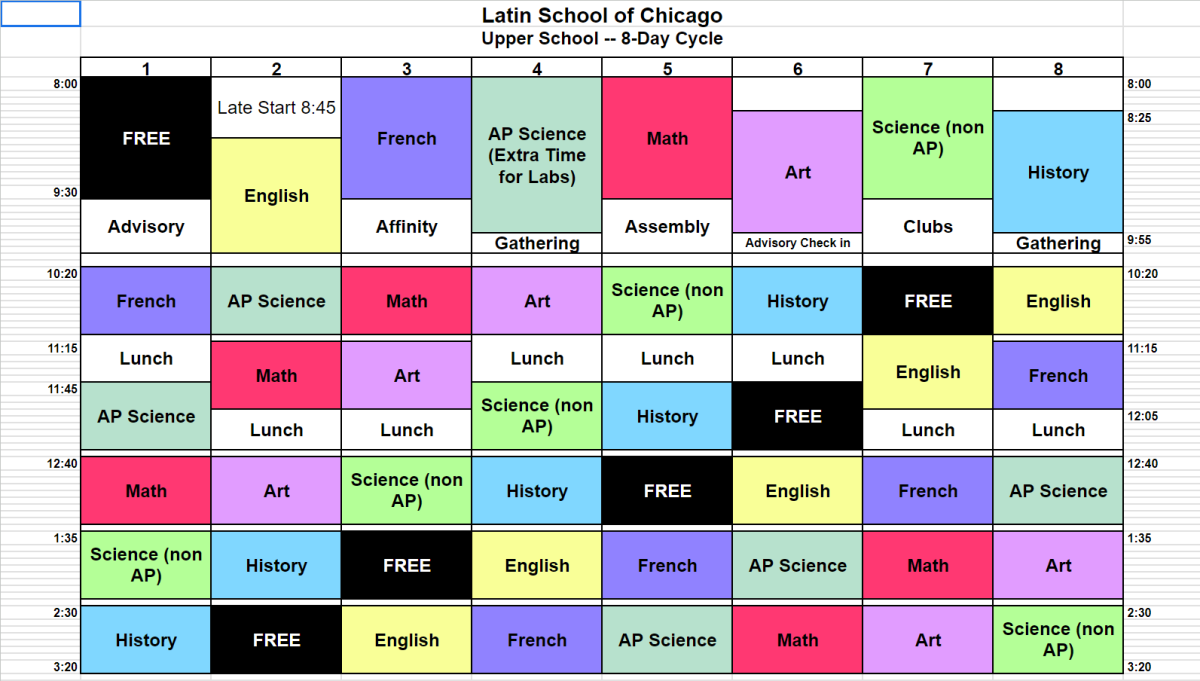

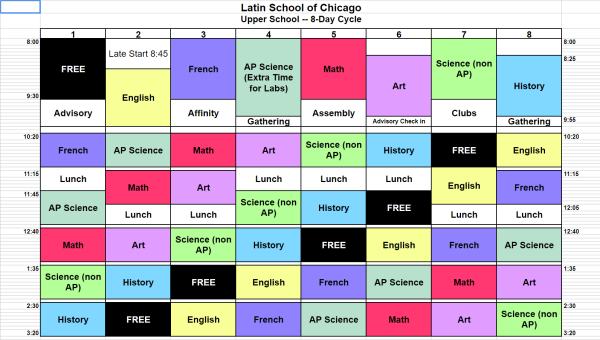

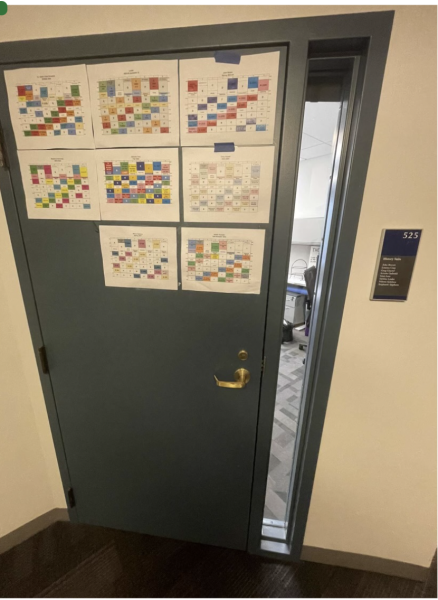

Structurally, the new midterm schedule followed a slightly different timetable than years past. This year, both days ran from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., with four “blocks” per day. Each block was broken into a shorter “A” or “B” test periods, if needed.

This timetable forced students to handle multiple exams within a few hours, which can be mentally taxing and draining. “Lots of my peers are feeling overwhelmed, and stress levels are going to go up,” junior Andres De Marco said.

The Upper School administration, however, foresaw this point of concern and worked to resolve any excessive amount of testing. Ms. Hennessy said, “We identified all conflicts and actively connected with students who would have more than two assessments in one day, and are impacted by this switch.”

To senior and Student Academic Board (SAB) Co-Head Carmen Quinones, what appears to be an excessive amount of tests seemed “unavoidable and inevitable.” Carmen believes that it is actually “pretty typical [to have multiple exams in a day] and definitely not because of the switch in schedule.”

This “switch” comes with a variety of implications, and, as a result, a variety of reactions. “[The new schedule] is essentially the same thing—the end goal remains the same,” Carmen said.

While the “end goal” of assessing students will remain identical, the process of doing so has transformed, and students, especially those in honors and AP courses, which account for 26% of all midterms, have felt the intensified pressure of the (now shortened) midterm exam week. “We don’t have as much time to study and prepare,” Andres, who takes three AP courses, said.

The shift in assessment methodology prompts consideration of its broader implications. “For SBG classes, a summative isn’t a part of standards,” Ms. Merrell said. “So if SBG is the direction we are moving, we won’t have any finals.”

Yet, a decrease in summative assessments did not necessarily reduce the number of classes students had to attend throughout the three midterm days. “Some of those midterms are not actually midterms,” Ms. Ilkchi said. Classes, such as the ninth-grade Global Studies: Visual Arts course, although not administering any assessments, met for a regular class on either Wednesday or Thursday.

Out of all 126 scheduled midterms, roughly 46% of the exams are in classes using the Standards Based Grading (SBG) system, suggesting that many teachers utilized these midterm “blocks” as normal class time, or open slots for reassessments.

This sudden switch in assessment methods raises a greater question about the need for summative midterm and final exams, in general.

Across the country, many schools have been bombarded with objections to the necessity of standardized testing, with top universities being pressured into eliminating required submissions of SAT and ACT scoring. In a maturing world of school testing, “less and less classes are giving those traditional, two-hour summative assessments,” Ms. Merrell said.

However, many still believe that summative testing is essential to education. “There is value [in] learning how to take a summative assessment and understanding how to study and prepare,” Ms. Ilkchi said. “Seeing how colleges have yet to go to SBG, I think we are prepping students for college.”

Looking to the future of Latin’s testing, or even just next year, students should not be surprised to see further modifications to the midterm testing schedule. “When [Mr. Baer] implemented this shorter period, he told faculty that we are going to try it this year and see how it goes,” Ms. Hennessy said. “ [Mr. Baer] is open to everything.”

Rohin Shah (’27) is a freshman at Latin and is delighted to write for The Forum. He hopes to become an engaged and investigative journalist, helping...