From Romania to North Avenue: A Humanitarian in Our Community

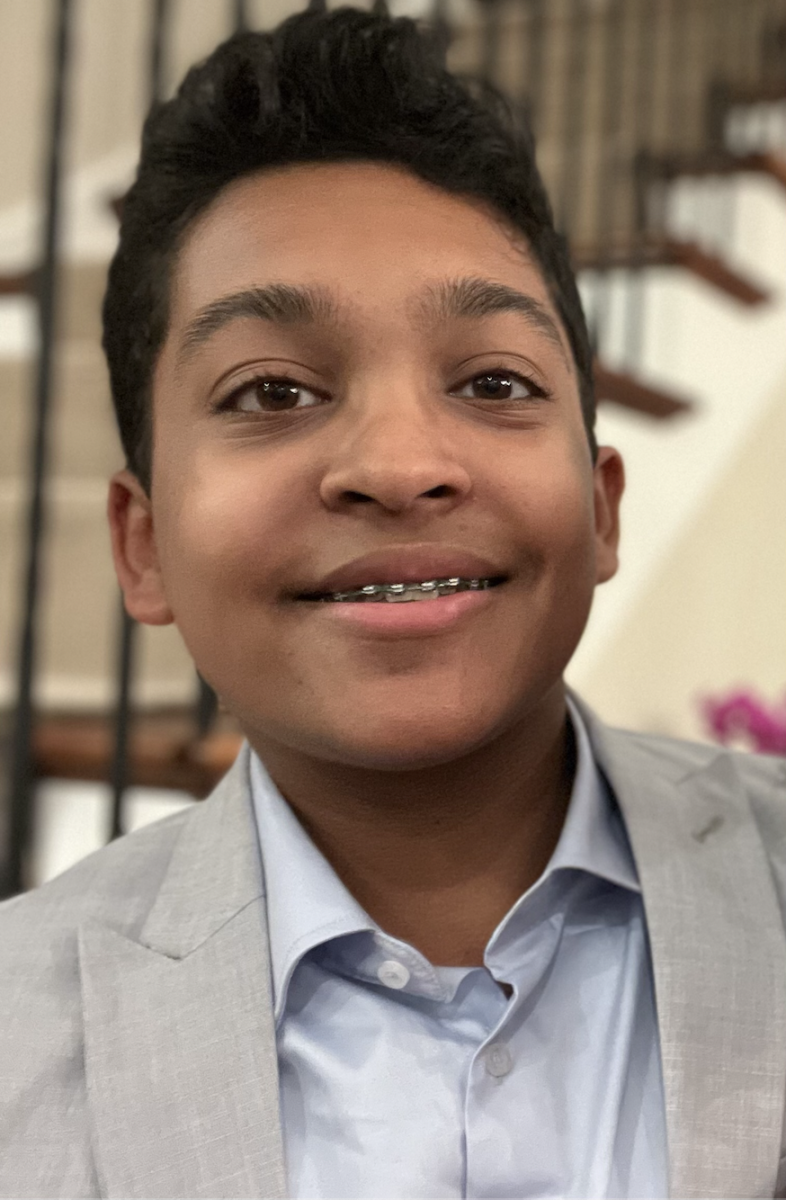

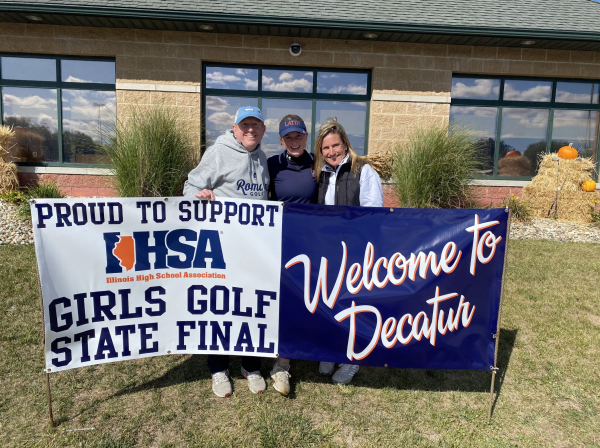

Ms Stephens taught US History and English as a second language while she was in post-communist Romania. Here her students are volunteering with orphans.

The phone rang, and a 22-year-old Stephanie Stephens picked it up to hear a message from the Peace Corps that would profoundly change her life: “You are eligible to teach in Romania.” With a teaching credential, an extreme fascination with the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War, and an excited mindset, Ms. Stephens headed to Romania, just three years after the oppressive communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu had collapsed.

When Latin students enter Ms. Stephens’ Honors European History classroom, they are met with a smiling Ms. Stephens, excited to share a colorful PowerPoint presentation that displays art during the French Revolution. Class begins, and she analyzes how historical figures might have felt during an ancient period from her empathetic perspective. Some of her students might not be aware of her past humanitarian work, yet they directly benefit from the historical authority she possesses.

Former Upper School English teacher David Marshall, who previously co-taught American Civilizations with Ms. Stephens, said, “A product of her experience in the Peace Corps is her sense of how cultural lenses influence the way we perceive events.” From teaching with Ms. Stephens, Mr. Marshall not only learned how much she cares for her students but also gained new teaching insights.

“She taught me that to truly master historical detail, you can’t reduce it to a single idea or perspective. You have to understand how everyone might have looked at it,” he said. Ms. Stephens’ prior experiences have informed her ability to empathize with the past, allowing her to teach European history with expertise.

In the summer of 1992, Ms. Stephens and her Peace Corps group arrived in Romania, but while her peers were sent to beautiful cities, Ms. Stephens was placed in the second-largest industrial mill city in Europe, called Galați. This big city, polluted and crowded, would intimidate anybody, especially a foreigner. “They put me here because they thought I was tough, but I was so scared. I had no idea what I was doing,” Ms. Stephens said.

Although she was alone in a new country without fluency in the language, Ms. Stephens continued to exercise her passion for teaching. She taught high school students English as a second language and taught U.S history. Romania had been cut off from the West for 50 years, so they wanted to open up their society and embrace change. Mr. Marshall said, “Having Americans there was an emblem of a new world.”

While the dictatorship was in the past, communism still lingered throughout Romania. “The communism culture was to fear Americans,” Ms. Stephens said. “There was always someone tapping my phone because everyone knew I was the American in town.” She even had her camera confiscated by police when she tried to take a picture of the first alleged democratic election. Some of Ms. Stephens’ co-workers were skeptical of their new American colleague, and her students had to adapt to a new American teaching style that was more collaborative than their traditional approach.

Ms. Stephens describes her Romanian students as “obedient,” as they were accustomed to not talking to each other and solely memorizing the teacher’s lectures. “They were not used to giving their opinion or leading discussions, and they were hit all the time,” Ms. Stephens said.

During her teaching in Romania, Ms. Stephens decided to conduct a community service project, and her students were quick to jump on this opportunity. “In their culture, they had never thought they could do anything like that,” she said. “They didn’t understand volunteerism.”

Under Ceaușescu’s leadership, contraception and abortion were not allowed, as he believed a large population would strengthen Romania’s economy. Many mothers could not afford to raise more children, so the children became orphans. After following the distressing orphan story in Romania, Ms. Stephens chose to center her service around helping the orphans.

“I was familiar with the Big Brothers Big Sisters of America organization, so I used it as a model and set up partnerships with my high school students with the orphans,” Ms. Stephens said. She and her students organized activities with the orphans, such as playing games or hosting dances.

While Ms. Stephens’ students were supportive of the orphans they worked with, a different group of orphans were ostracized and in desperate need of help. In Ceaușescu’s same attempt to bolster the population, his government inoculated babies with a vaccine intended to “strengthen” them, but they didn’t realize the needles used were contaminated with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). “They infected a whole generation of babies,” Ms. Stephens said. After the babies were infected with HIV, they developed AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). At the time, Romanians did not understand AIDS and therefore feared it, so they imposed isolation on the infected babies.

Aside from her community service project with her students, Ms. Stephens went alone to visit the orphanages of children with AIDS. When Ms. Stephens entered the first orphanage, she was surrounded by little children who were highly malnourished and underdeveloped. “It was the saddest thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” Ms. Stephens said. As she looked around the orphanage, she noticed the children all partaking in a similar, agonizing activity. “To get some kind of stimulation, since no one would hug them, they would just hit their heads against the cribs all day long, just to feel something,” she said. During her time volunteering, Ms. Stephens would simply hold the children, providing them with some sense of comfort and belonging.

Ms. Stephens worked alongside aid workers from other countries who also cared for the orphans. She recalled the aid workers having to lock their supplies from the Romanian workers or else they would get stolen. “There was a mentality that these kids aren’t going to make it anyways, so they don’t need these products,” she said. Unfortunately, without proper medication, most of these children did not survive. “It was so heartbreaking,” Ms. Stephens said.

Although Ms. Stephens’ time in Romania ended at age 24, she continues her humanitarian work daily by using her past emotional experiences to teach high school students. Senior Thor Graham, a student in Ms. Stephens’s Honors European History class, discussed how Ms. Stephens’ teaching style has benefited him. “She gives people inspiration to be empathetic,” he said. “She knows firsthand about European history, and we learn in a more freeing class setting where we are always able to discuss.”

Senior Giuliana Dowd, another student in Ms. Stephens European history class, also values Ms. Stephens’s empathetic teaching approach. When Giuliana reached out to ask for a small extension on an essay, Ms. Stephens’s understanding response stood out to her. “She made me feel very supported, especially during such a busy time,” Giuliana said.

Ms. Stephens teaches her students about historical totalitarian regimes, but living in the aftermath of one has awarded her with a more profound understanding of the importance of equality. Of her time in Romania, she said, “It heightened my appreciation for democracy but also my awareness of how vulnerable democracy is, something that cannot be taken for granted.”

Zach McArthur • Feb 2, 2022 at 8:37 am

Great article, Marissa, on an inspiring teacher! I see shades of Ms. Stephens empathetic mindset in your work in Best Buddies. Her kindness and care for others, no matter their position, has clearly rubbed off on you!

Naomi Altman • Jan 18, 2022 at 7:49 pm

Ms. Stephens is the best! Nice article!

Ann McGlinn • Jan 18, 2022 at 6:12 pm

Latin is beyond fortunate to have such a passionate, talented teacher, and I’m lucky to have such an inspiring colleague

John W Stephens • Jan 19, 2022 at 8:19 am

While both extremes of the political spectrum are successfully coercing administrators and school districts to indoctrinate students in their positions, Stephanie should be commended for exposing her students to an array of ideas and for having the faith in her students to know that the range of conclusions a free-thinking community will inevitably draw, will make the community better when presented in an atmosphere of empathy and respect. Proud.