High Schoolers Around the World: We Will Make It

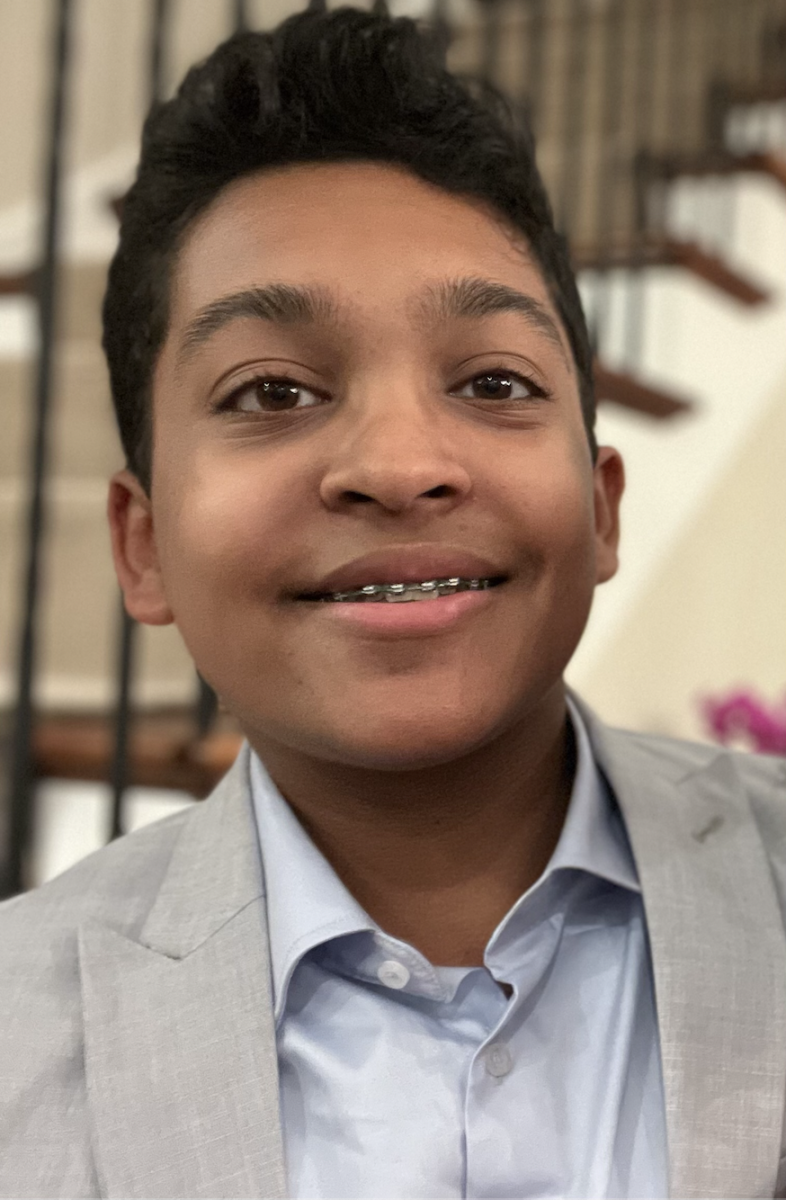

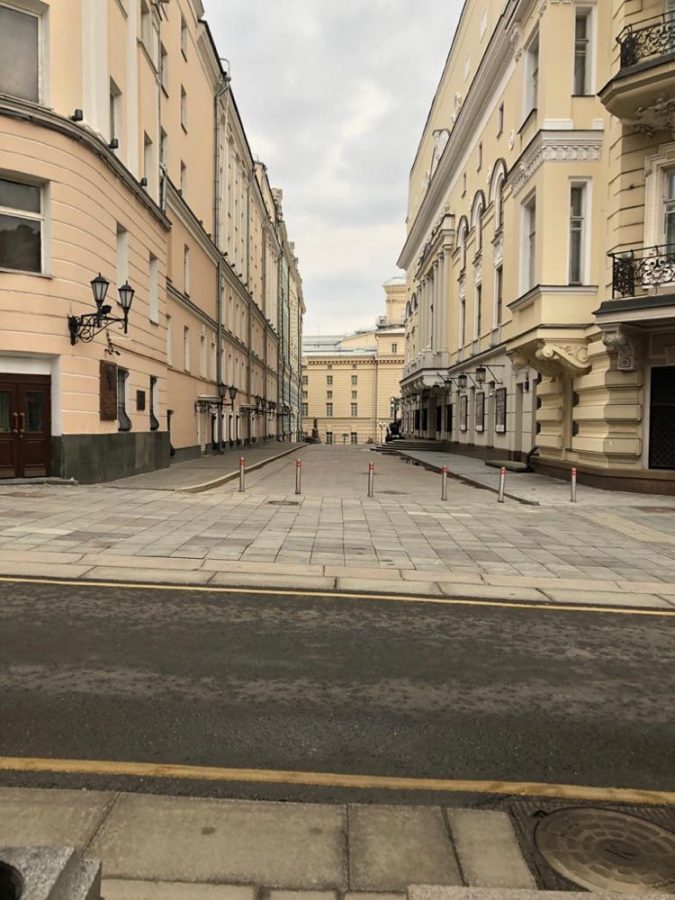

Taken by Maria's mother, Marina Parfenenko, on her way to work.

Just off of Moscow’s famous Red Square, the once bustling Tverskaya Street now sits empty. “It’s kind of sad that we can’t walk around and go to the Red Square and run around in circles,” says Maria.

April 18, 2020

As coronavirus continues to upend life in the United States, it is easy to forget about the billions of people across the world that are also affected by the pandemic. Below, high schoolers across the world speak about how their lives have changed since the outbreak. As Farouk Chehabeddine, a high schooler from Geneva, Switzerland, puts it, “We are all in a similar situation in that we all have to stay inside and we’re limited to what we can do.” While staying home can be hard, it is an absolutely necessary evil. Federico Peri, from Florence, Italy, says, “I’ll just tell everybody to stay home because really it’s the best thing that anyone can do and the quickest way to stop the virus. Like we say in Italy, “Andrà tutto bene. Ce la fermano,” which means “everything is going to be okay, we will make it.”

School

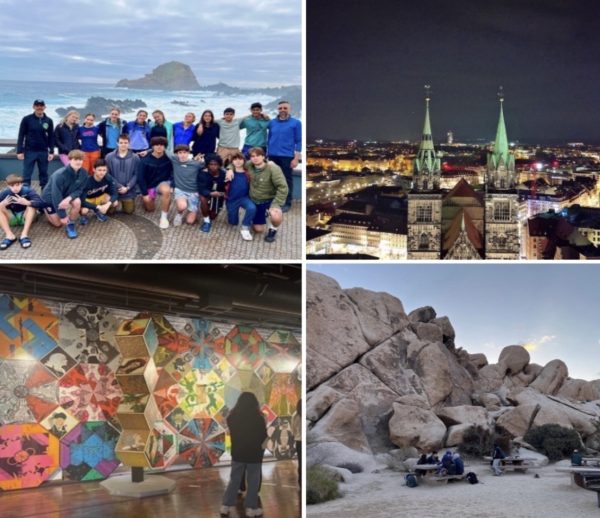

For high schoolers across the globe, COVID-19 has completely changed the way they go to school. Kemi Olaleye, who attends a private school in Cape Town, South Africa, has shifted to an online system similar to that at Latin, with a combination of asynchronous homework and synchronous Zoom classes. She says, “We are a private school so we have teachers that have had the time to decide and tailor it to all of our needs, so everything’s going pretty well, to be honest.” 12,000 miles North, Farouk’s IB school in Switzerland has shifted to a similar system. “It’s not ideal, but it works.”

Other students express the struggles of learning new material without actually being in class. A private school in London, England, hopes to implement video calls after Easter Holidays. Emma Stoichescu, a Year 12, says, “so far they’ve only been sending us work which you don’t learn from it as well as them teaching it to you.” Even when schools do use video calls, learning can be difficult. Federico Peri says, “There are video lessons which sometimes are a pain. Like, if our math teacher is explaining a new subject it’s really hard to comprehend the new subject online only listening to her voice.” Angela Girardot expresses her struggles with online classes in Paris, France. “Not having lessons in a classroom anymore is very complicated. Our way of working is effectively very different and can be difficult.” Students understand that while this new method of learning is difficult for them, it is hard for their teachers as well. In Moscow, Russia, Maria Parfenenko says, “it’s very stressful for the teachers mostly because a lot of them are old and they’re struggling to handle technology.”

For many, the most stressful part of online school is changes to testing. Angus Power, a high schooler in Sydney, Australia, says, “we just did online assessments which was super difficult to stay motivated and focused and work hard.” Others are experiencing concerning delays in tests that they will count on for college admissions. In Russia, Maria says, “we are mainly focusing on preparing for the exams which have been moved for two weeks already and don’t know what the future is.” She was counting on these exams to get her into university, and says, “the time loop to give our documentations to the university for consideration, they are not being accommodating to the time where I get my results so I’m really stressed.” For some, key tests have been cancelled altogether. In the United Kingdom, A-levels, which are the key component in university placement, were cancelled, and administrators have to use past grades and mock test scores to make decisions instead. All of years 12 and 13 (grades 11 and 12) are spent preparing for these tests, so the decision to cancel them leaves year 13s frustrated and uncertain about the future. All International Baccalaureate exams have also been cancelled, and Farouk says that at his school in Geneva, “for seniors they are not going to be doing any of their exams and they are done for the year.” IB seniors aren’t the only ones who might be out of school for the year, as Kemi says that in South Africa, “public schools haven’t started so I don’t know if they’re going to do online schooling or just, I think what’s happening is just they are closing down and then their holidays will be taken from their summer break.”

The hardest part has without a doubt been the inability to go into school, see friends and really do all of the things that make our final year fun. The fact that so much might be cancelled like eighteenth birthdays and stuff we all looked forward to and kept us moving throughout the year.

— Angus Power

No matter how effective these new systems are academically, students miss seeing their friends. Federico says, “Definitely I miss hanging out with my friends, my new classmates, guys and girls from school.” Even outside of school, “I miss hanging out in the center because I love that, and the hardest part about making these changes is accepting the fact that I’ll probably have to stay at home for another month.” Farouk agrees, and says “I wouldn’t say I miss school but I guess I miss socializing. I don’t get to see all of my friends because we are very limited to where we can go.” This is particularly hard for students who are in their last year of high school. Angus said, “The hardest part has without a doubt been the inability to go into school, see friends and really do all of the things that make our final year fun. The fact that so much might be cancelled like eighteenth birthdays and stuff we all looked forward to and kept us moving throughout the year.”

Getting Outside

While most students are encouraged to limit social interactions to slow the spread of the virus as much as possible, national governments’ recommendations differ on how this should be done. The United States, for instance, allows people to run and walk outside as much as they please so long as they stay six feet away from others and do not enter closed off areas. In many other countries, this is not the case. In the United Kingdom, “officially you can only go outside once a day for exercise,” says Emma. People do not necessarily listen to these recommendations, however. “So many people you still see, or people on their stories, are going out for walks ten times a day, like ‘accidentally’ running into people. A lot of people obviously have realized that [the virus] is serious but not enough.” France has also limited physical exercise. Angela says, “We cannot move from our home except to run necessary errands, or to exercise but not for more than an hour and not for more than one kilometer.”

Other countries have banned exercise altogether. In Russia, says Maria, “you are allowed to leave the house to seek medical attention, get medication, get groceries, and walk your dog within 100 meters (1/10 of a mile) away from your home,” but not to go for a walk or run. “A lot of people just walk their dogs anywhere so a lot of them abuse their dogs to walk around.” Police are keen on enforcing these measures, and she describes a scene that was in the news last week: “A man was walking his dog but his dog was really far away so it looked like he was just walking around and so the police approached him, so he threw a fit and they ended up arresting him.” In many places, going to church is no longer an option. For Masha, “To hear the head of the church tell people to not go to church and stay home has been mildly terrifying simply because it feels like, you know, the church has been around for 2000 years so they should be able to handle everything.”

For larger populated areas we’ve got the army and they’re known to use physical force. I think currently eight people have died from army encounters because they’re outside, which is interesting because it’s more than the amount of people that have died from coronavirus in South Africa.

— Kemi Olaleye

In South Africa, people are not even allowed to walk their dogs. Kemi says, “Basically you are not allowed to leave the house unless you are going to the grocery store and only one person from the family can go to the grocery store at a time.” The country is not afraid to do whatever is deemed necessary to ensure people follow these guidelines. In Kemi’s suburb, “it’s just police and they’ll patrol and you’ll be fined or something.” However, “for larger populated areas we’ve got the army and they’re known to use physical force. I think currently eight people have died from army encounters because they’re outside, which is interesting because it’s more than the amount of people that have died from coronavirus in South Africa.” (Since this interview, South Africa’s COVID-19 deaths have surpassed eight.)

Italy, which has been hit particularly hard by the virus, has similarly strict regulations. Federico says, “The last time I went out was on the 15th of March.” Since then, the government has prohibited leaving the house except for meeting essential needs, or walking small children or babies 200 meters away. Federico says, “now my family is lucky because we have a garden so we don’t have to worry much about that, we just stay in our garden and it’s all right.” If you break these rules, “you have to pay up to 3000 euros if I’m not mistaken. And, you can get a legal note and also put into jail if you break these laws.” This inability to get outside can be demoralizing. “The hardest part about making these changes is accepting the fact that I’ll probably have to stay at home for another month or two because you know it takes a while to get rid of this virus. What also scared me the most is that I’m not sure that we’re going to go back to our normal life before the virus.”

Grocery Shopping

One of the only things that is deemed essential everywhere is grocery shopping. However, from shortages to long lines, buying food does not look the same as it used to. Kemi says that in South Africa, “Only five people are allowed in the grocery store. There’s like a crazy line which is quite dumb to be honest because obviously the people in the line are probably the ones who will be getting sick because they are all squashed on each other.” Even once people get into the store, there are strict guidelines on what people can buy. “My mom’s friend went to the shop recently and she put a magazine in her grocery bag and they wouldn’t let her take it, and a hairbrush, and they were like no you are only allowed to buy consumables.”

In Russia, Maria says, “Because I am in the countryside, we can walk to the nearest grocery store or food market so luckily we are not experiencing food shortages.” In cities around the world, it is a different story. Emma says, “Even with food and toilet paper and tissues, in London it’s so hard to find them now, especially at the beginning of the craze where everyone’s like oh my god corona and everyone starts raiding all the shops. Stuff that you always buy like hummus or even bread, it’s gone so fast.” And, similar to in the United States and South Africa, just getting inside the store can be difficult. “You have to queue outside two meters away from the other person, and it takes a long time to get into the shop.”

Government Rhetoric

Across the world, coronavirus demands government response. In some countries, leaders’ actions have been met with enthusiasm and approval, but in others, they have caused increased feelings of anger and distrust. Compared to those of many countries in Europe, South Africa’s case counts are extremely low, and its deaths even lower. Kemi says, “Our government took it very seriously very quickly and lot’s of people were shocked by that because that doesn’t happen very often.” Despite the low number of infections, people in Kemi’s suburb are taking the disease very seriously. “Lots of people are very very scared as well, to the point where you can’t wave at someone or look at somebody in the eye if you’re walking across the street.” This fear, coupled with a quick government response, has shifted opinions of a public that was formerly very critical of their leaders. “A lot of people that weren’t pro South Africa ever are a lot happier to be here now. Especially in the younger demographic, so teens are really digging the president currently because of everything he’s been doing. He’s been very communicative which is not very common so he’s been sending out something new almost every night and keeping everyone updated.”

However, “no one’s being compensated financially.” And with South Africa’s large wealth gap, these closures have caused unrest in already impoverished areas that are barely affected by the disease in and of itself. “We’ve tokened it as the rich people disease because it’s a very international disease so typically the only people that really have it currently are the ones that have traveled somewhere or been in contact with someone that went somewhere.” Partially because of this, “People in the townships aren’t really conforming that much. It’s a really tiny place so you can’t really stay inside.”

Russia is also struggling to help those most affected by the closures. The president recently extended stay-at-home orders to April 30th, and Maria says, “At the moment there is no social support for anybody so a lot of people either lost their jobs or are struggling financially, so there’s a lot of negativity about his decision.”

The UK has also experienced a lot of criticism regarding how leaders have handled the crisis. Originally, Prime Minister Boris Johnson supported the idea of keeping everything open in an attempt to achieve herd immunity. According to Emma, this meant “Just let everyone get it and the next time it comes around it’s fine, like it’s fine if people get it the first time they won’t get sick the second time.” She disputes this idea, saying, “But if you do it right, you don’t need to get it the first time.” She isn’t the only one who disagrees with the Prime Minister, who was just released from the ICU after catching the virus. “A lot of people have hated the stuff he said. People say that he isn’t taking enough action. And also, we were one of the last European countries to shut our schools down.” On top of that, between the media and different government authorities, Emma says, “There’s so much information just contradicting each other.”

Compared to the US’s over 600,000 and the UK’s close to 100,000 infections, Australia’s infection count of 6,414 (as of Wednesday, April 15th) is relatively low. Angus says, “Australia has done an outstanding job with this crisis and it isn’t commented on enough. On top of that we have kept the death toll down which is something to really be proud of.” Additionally, “Testing in Australia is very easy to get, as long as you display symptoms you are instantly given a test which is really awesome and probably one of the reasons we’re pushing through and flattening the curve so quickly.” COVID-19 tests are easy to come by in Switzerland as well. Farouk says, “They provide a contact for doctors and if you do think that you have the coronavirus you can just check the contact number and they will provide it for you.”

Unfortunately, this is not the case in the United States. Alexis Geller, a high schooler living in New York City, says, “It is not that easy for most people to get tested. This is a big issue in my opinion—I don’t see us flattening the curve successfully without us knowing whether or not we have the virus or not.”

In Italy, a country that was devastated by the pandemic early on, Federico says, “local and national governments have taken good precautions.” The government is working hard to enforce these precautions. “There are drones now checking on people other than military and police, so it’s pretty strict.” Yet, some people aren’t listening. “Most people have responded well, probably I’d say a good 85-90%, but there are still tons of people that don’t understand that they have to stay home. Just yesterday, on Easter, there were ten kilometers, so like six miles, of queue on the Autostrade from Rome to Ostia, because people wanted to spend a nice Easter I guess with their family or they probably wanted to go to the seaside and that was a bit of a scandal.”

Nationalism

Even before COVID-19, there was a lot of talk of nationalism rising around the globe. On the one hand, nations must work across borders to solve this global crisis. On the other, now more than ever, countries must focus on keeping their own people healthy and safe. To limit the spread of the virus, people across the globe are forbidden from traveling internationally. Farouk says, “I live in Geneva and that borders France and for example I have a lot of friends that live in France and hence we are not allowed to cross borders so that’s also something they’ve been strict on.”

There were these people who approached a person and simply were asking him to get off the train. It was a huge mess and basically, what I got out of that was that people were starting to get really worried that Asian people would have the coronavirus. They were basically saying, ‘Go back to your country,’ which was horrible.

— Farouk Chehabeddine

Keeping people close to home makes sense, but in some instances, the pandemic has also incited anti-Chinese sentiment. Farouk remembers an experience downtown around the time when the virus first broke out in China. “There were these people who approached a person and simply were asking him to get off the train. It was a huge mess and basically, what I got out of that was that people were starting to get really worried that Asian people would have the coronavirus. They were basically saying, ‘Go back to your country,’ which was horrible.” With experiences like these, Farouk says, “I think there has been a small rise in nationalism.” When asked if there has been a rise in nationalism in the UK, Emma says, “Originally, against Asians, even a very good friend of mine. Some man very loudly was like, ‘Oh my God she’s Chinese!” and yelled it out loud so definitely towards the beginning.”

Perhaps this form of nationalism was just thinly veiled racism, as many report these comments stopping when the virus spread to Europe. Emma says, “As Italy’s numbers started to rise, I think it was seen as a global thing and not just as Eastern/Asian.” Maria says that in Russia, “I don’t feel like there has been any nationalism going on because we are very sorry for Europe, and we are very sorry for Italy. When it was in China we didn’t really care as much because it feels far away, but when it started impacting Europe we just got really, you know, stressed.”

However, Maria points out that not everyone feels this way. In regards to the president’s decisions, some feel, “You are supposed to care for your people and why are we sending help to Italy and why are we sending help to other countries in Europe while your own people are struggling and not certain about what tomorrow will bring.”

In other ways, increased national pride can be a driving force in getting people through the pandemic. Kemi says, “South Africa’s not a very nationalist country, but I guess a lot of people that weren’t pro South Africa ever are a lot happier to be here now. It’s like, I’m okay, I don’t really want to move to Australia currently so they’re not handing it to us.” In London, Emma says, “Every Thursday I believe at 8:00 everyone opens their windows and claps for the NHS which is our public, well, National Health Service.” Similar scenes are happening across the United States. Alexis says, “Out on Long Island, where I am, we have been driving over to Southampton Hospital and clapping, screaming, and honking for out doctors and nurses. It is one hundred percent the highlight of my quarantine.”

Maria says, “There’s this phrase ‘Мы Русские… С Нами Бог!’ or ‘Russians, God is with us!’ So there’s been a lot of jokes about this epidemic is not going to go anywhere, we’re just too unhappy and too angry for it to impact us. A lot of the epidemics that happened in Europe didn’t really impact Russia because we have a very large territory and not very many people and it’s cold, so a lot of the stuff died on its way here so we kind of remember that.” In addition to allowing people to make jokes, national pride helps keep Russians mentally strong. “We have this mentality of we can do anything, we can combat anything, but I don’t feel there has been any nationalism going on.”

Whether or not it is perceived as nationalism, it is important that countries stay unified under the crisis. Federico says that in Italy, “I don’t see a rise in nationalism because we are sticking all together, our Prime Minister is being helped by his party and the opposition without too much contrast so they are both helping, there is not one that is prevailing the other. We are all united and we are all in this and let’s hope it ends soon.” This rhetoric of unity has made its way to France as well, and Angela says, “The country is all united to save lives and eradicate the pandemic.”