Synthesizing Latin’s Earned Honors History System

Rather than having what will be on the transcript decided before them, junior history students are given the option to earn it.

When the History Department decided to eliminate the honors U.S. history course in 2021, community-wide responses were varied. Some were relieved that the divide being created between students would come to an end, and some worried that their education and experience would suffer. But at that moment, nobody, including the History Department, understood what the switch would look like. It was not until it was implemented that it all started to come together.

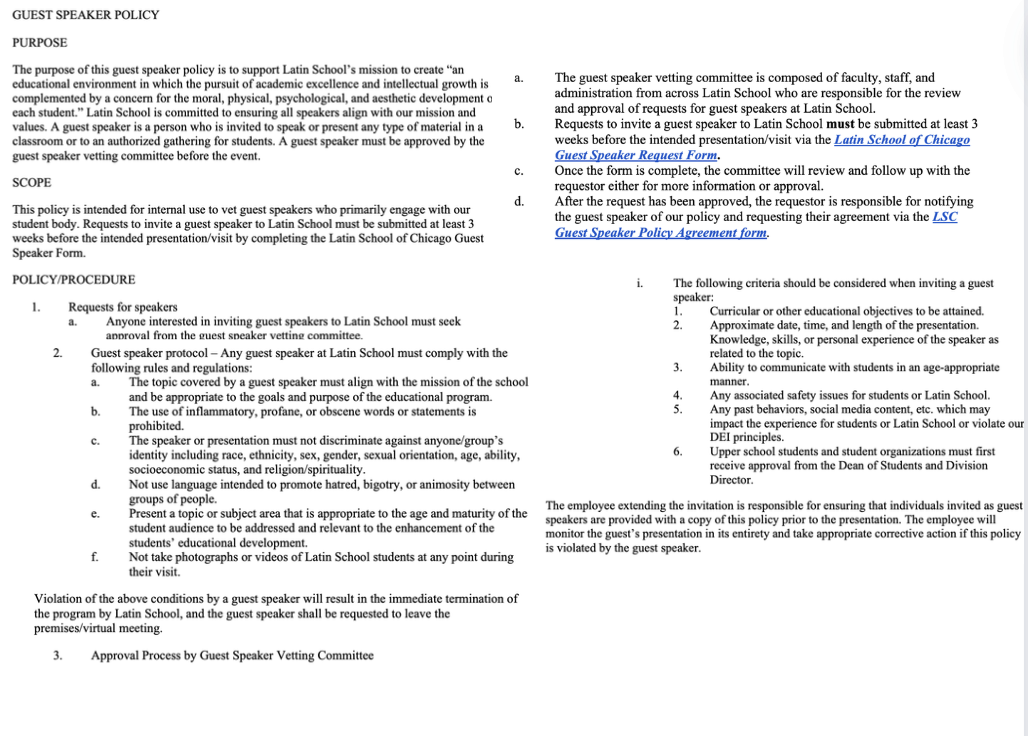

Latin has not offered AP U.S. History in over a decade, yet students still had the option of honors. Students were evaluated based on their performance in history throughout their freshman and sophomore years and had the option to appeal if they were not happy with their placement. Needless to say, earned honors was new for many community members, including the faculty.

Upper School history teacher Ernesto Cruz, who was involved in designing the earned honors program, said, “It was a pretty radical shift from what we’ve done in the past. There’s a long multi-decade history of what honors looks like in the humanities at Latin. So frankly, on the history side, I think a lot of what we can and can’t do with honors in history at Latin was decided before any of us got here. That’s the other part of it. We are playing with rules that were written by people who are long since retired.”

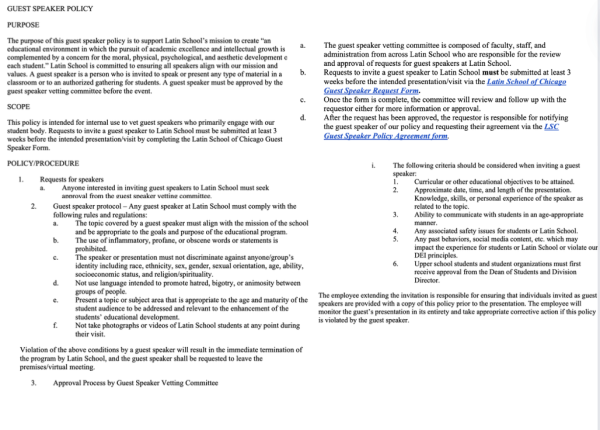

And those “rules” were not reflected anywhere else in the department. Every freshman takes the same history course, Global Studies. Every sophomore takes two semester-long college prep-level history electives. Any non-honors course at Latin is considered to be college prep level. So ultimately, the department decided it was time to ax the honors class as a whole.

In addition, the placement process was faulty, according to the presentation former Department Chair Cara Gallagher gave in the spring of 2021. There was no test to decide who got to be in honors and who did not. It was based on conversations among the department about each student.

Upper School U.S. history teacher Debbie Linder said, “Sometimes kids get put into a more challenging class because they do a lot more work and not because they understand it on a very deep level. And sometimes kids get put into a class that’s not challenging because they do not put in as much work but understand it on a very deep level.”

The current system was initially met with backlash because students and parents worried about how each individual would be impacted. “The level of conversation is always heightening,” Ms. Linder said. “I don’t think any kids who are considered to be a ‘weaker’ student brings anybody down. It actually allows for kids to grow. I know for sure that there are students who have been in my classes who would not have been put in the honors track who got honors by the end of the year because they were allowed to be in that space.”

It was then decided that the honors course would be removed from the curriculum. Enter synthesis.

Synthesis is defined as “the combination of ideas to form a theory or system,” and in U.S. history, that looks like “[demonstrating] a deliberative stance towards the past that recognizes the provisional nature of knowledge.”

Students are evaluated beginning second semester on synthesis, and if they receive primarily 3’s and 4’s, they will get the honors distinction on their transcript.

The repercussions that followed the original announcement of the program are still relevant for students now, almost three years later.

“I understand why the school did the earned honors system, and I understand that it was probably difficult to differentiate kids at the history level,” junior Juliette Katz said. “But I think it’s frustrating because Latin has a lot of honors STEM opportunities, and I understand that they did it, but it’s not necessarily fair that they took away their one honors humanities class for juniors.”

Currently, Latin students can take every math and science course at the honors or regular level, as long as departmental permission is granted. The same goes for AP classes. With regard to the humanities, students can “earn” their honors in U.S. history and take “Advanced Topics” courses senior year, or junior year with departmental permission.

But beyond the longtime honors STEM versus humanities debate, students found other difficulties within the system.

“I wasn’t a huge fan of the earned honors system,” senior Nisa Ahmed said. “Personally, I would’ve preferred to know for sure if I was going to be doing honors level work or non-honors level work the whole year. Also, the fact that the deciding factor of whether or not you get an honors credit was the synthesis strand didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me, because I thought that being in an honors-level class was a little more multifaceted than just one strand.”

Similarly, junior Elana Goldwin said, “I think sometimes I get a little confused why it is purely based on the synthesis strand and not all of them together. I hope to see why synthesis is the pure strand for obtaining honors as we go into the second semester.”

Last year, students were told that even though they were being graded on synthesis first semester, it was not going to count toward their overall synthesis grade. However, when they returned to school the second semester, the opposite was true—all first-semester synthesis grades would contribute to final grades.

“I remember hearing that people had been told that our first-semester synthesis grades weren’t going to count, but it ended up being that they actually did count, which was really confusing,” Nisa said. “I think overall, the way that synthesis and how it was presented to us was pretty confusing, to me at least, and I had to learn by experience.”

Ms. Linder said, “One thing we are really consistent about this year is that synthesis is formative first semester and summative second semester. Clearly, there were some things last year that were not as consistent.”

The primary struggle that students have had, however, is a fairly large one. Students don’t seem to quite understand what synthesis even is.

“I think synthesis itself as a strand is really confusing,” Juliette said. “Granted, the teachers dive into it a lot more in the second semester because synthesis counts second semester, but I think it’s kind of overwhelming right now.”

Senior Coco Schuster said, “I was pretty confused what synthesis was, and I think a lot of my other classmates were as well. I think the most confusing part was how we were supposed to demonstrate mastery of it.”

Nisa said, “By the end of the year, I think I had a decent understanding of what synthesis meant based on the grades I had been receiving and the connections that I was making, but it took me way too many bad grades to get the hang of.”

“The thing is that synthesis, just like history, is something that is not definitive in the same way that an equation is,” Ms. Linder said. “Sometimes it’s hard to articulate to kids who don’t understand what it is, and I think that as historians, we are so immersed, and it’s kind of how we think all the time. For students who may not have any understanding of how to think like a historian, getting them there is a challenge.”

Ultimately, the number of students earning the honors distinction is not so different from the number of students that were being placed into the honors course, according to Mr. Cruz. While there has been a slight increase in honors history students, “it’s not overwhelmingly more,” he said.

Since the introduction of the earned honors system two and a half years ago, it has come a long way, and it still has areas of improvement, just like any good program does. “I really want to get feedback on how the kids have been feeling about it over the past couple of years,” Ms. Linder said. “I want to make sure we are doing this right, and I hope I’m getting better at it as I go.”

Eliza Lampert (’24) is a senior at Latin and is overjoyed to serve as one of this year’s Editors-in-Chief. During her time writing for The Forum, she...

Deborah Linder • Dec 15, 2023 at 5:11 pm

Good article, Eliza. Thank you for writing about it.