Will Nuelle

Something I struggled with this summer was my own independence. Wait. Maybe that was the wrong way to put it—it sounds too much like I staged a bloody revolution against some kind of oppressive social injustice. No, no, no, I didn’t mean it like that.

Let me rephrase it: something I struggled with this summer was what it means to be independent.

At first it was just a feeling, a tiny morsel inside my hypothetical, always-questioning mind. “Am I really independent?” I asked myself. If I were to write it down on paper, it would certainly seem so; I am allowed to be friends with who I want, go (mostly) where I want, listen to what I want, and to generally be who I want. Am I really missing something? I imagine most Latin kids feel similarly. We have everything we want—opportunity, care, love—but maybe there is something missing; something we’re longing for; something that I’m certainly searching for: true independence.

Admittedly, I was mad this summer when I got in trouble with my parents for sneaking out of the house at 2 AM to hang out with friends. I got caught. Stupid? Yes, it was stupid. But I also think it’s something I have to do at least once before the end of high school; a bucket list type thing, I guess. My punishment wasn’t even that harsh. I had an earlier curfew for a few months, which wasn’t that bad. But I began to get a sense of unfair restriction—whether that came from an entitled sense or a legitimate one, I did not care. I was, in a biased sense, limited by my parents. My unalienable human rights, I felt, had been stripped. It seemed stupid. I could physically get up and walk out the door and be home later than my curfew and be completely fine, alive and happy, so how did someone have the power to take that away from me? Well, the short answer to that hypothetical question is that my parents are paying my phone bill (among other important things). But I discovered two things from that occurrence; the first is that ideally I should be in singular control of my own life and the second is that I should never commit a felony because jail would not suit me well.

I didn’t really know how to go on from there. This idea that I’m not really in control of my own life began to haunt me. Obviously, I’m in physical control of my own self, and I feel like I’m in control mentally—I don’t really believe in predestination or anything like that, I believe that I have free will to make my own choices—but am I actually?

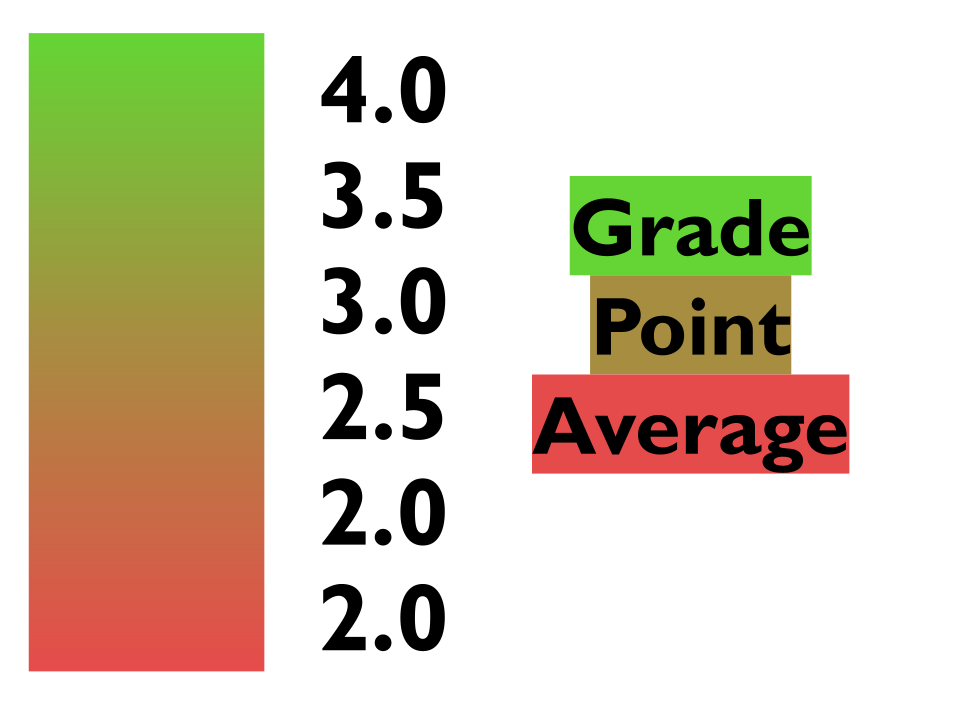

From birth, my parents have been by my side—something that is undoubtedly a luxury. Though the pros obviously outweigh the cons, it can be a double-edged sword. They have been my greatest influence during my formative years, during which I have been figuring out my opinions and what I want to do and who exactly I am as a person. As my strongest influences, I have naturally adopted many, if not all, of their opinions in some way shape or form. I couldn’t help thinking this summer that I am the embodiment of everything they wanted from themselves; that I am a puppet for someone else’s wishes, simply hanging on strings. It’s a pretty twisted feeling sometimes, to feel psychologically independent, but perhaps not actually being completely so. It’s not that I want the opposite of what my parents want for me. In fact the problem is that I often want the same as what my parents want, but have trouble deciding if it’s really my own desire rather than a desire my parents have instilled in me. For instance, something I want—and that I think a lot of Latin students agree with—is to perform well in school for both intrinsic and extrinsic motives. It’s something that I believe in, but my parents expect that from me and have since I was young, so I must question whether it’s really me who wants to do well. And to this point I can’t complain because I have worked hard and done well. But is this sense of motivation influenced by me or is it superficial?

Sometimes it’s greater than just my parents. Although it’s never explicitly stated, society—Latin included—wants everyone to move down the pipeline. The pipeline that pushes all students to be ready for college, which implies that everyone should go to college where they teach you how to do a job, which implies that you will have a job in the field that they expect you to have a job in, so then you will have that job and be working for someone, and you will move up over time, but only because someone else chose for you to move up, and then you will want to keep moving up, but there’s many other people who want that same job, and then maybe you realize you’re not even happy. But are you even happy? It’s impossible to say because you’ve never learned to think for yourself, to think without this giant crutch of society. You could never know if you’re truly happy because all your measures of happiness depend on what your school or your society have influenced you to think. At that point it’d be impossible to know yourself under those circumstances. It’s no one’s fault either. All of this happens subconsciously; there is no explicit statement from anyone telling you what to think and when to think it. It’s simply ingrained into our heads by constant exposure and constant influence from minds other than our own.

And that scares the crap out of me.

So then what’s our duty as high school students? We shouldn’t tune out all influences, surely, for the purpose of achieving some sort of elusive “mental independence.” What we should do, perhaps, is try to find our own voice and sort out what we want and what others—friends, parents, school, society—want for us. Of course, if you’re 18 or under you’re (probably) still living with your parents. They are legally in charge of your life. However, that doesn’t mean that you can’t think independently of them. Understand where “you” end and where “they”—not just your parents—begin. That’s where you might begin to find true independence.

]]>