A Sanctuary City: Exploring Chicago’s Migrant Crisis

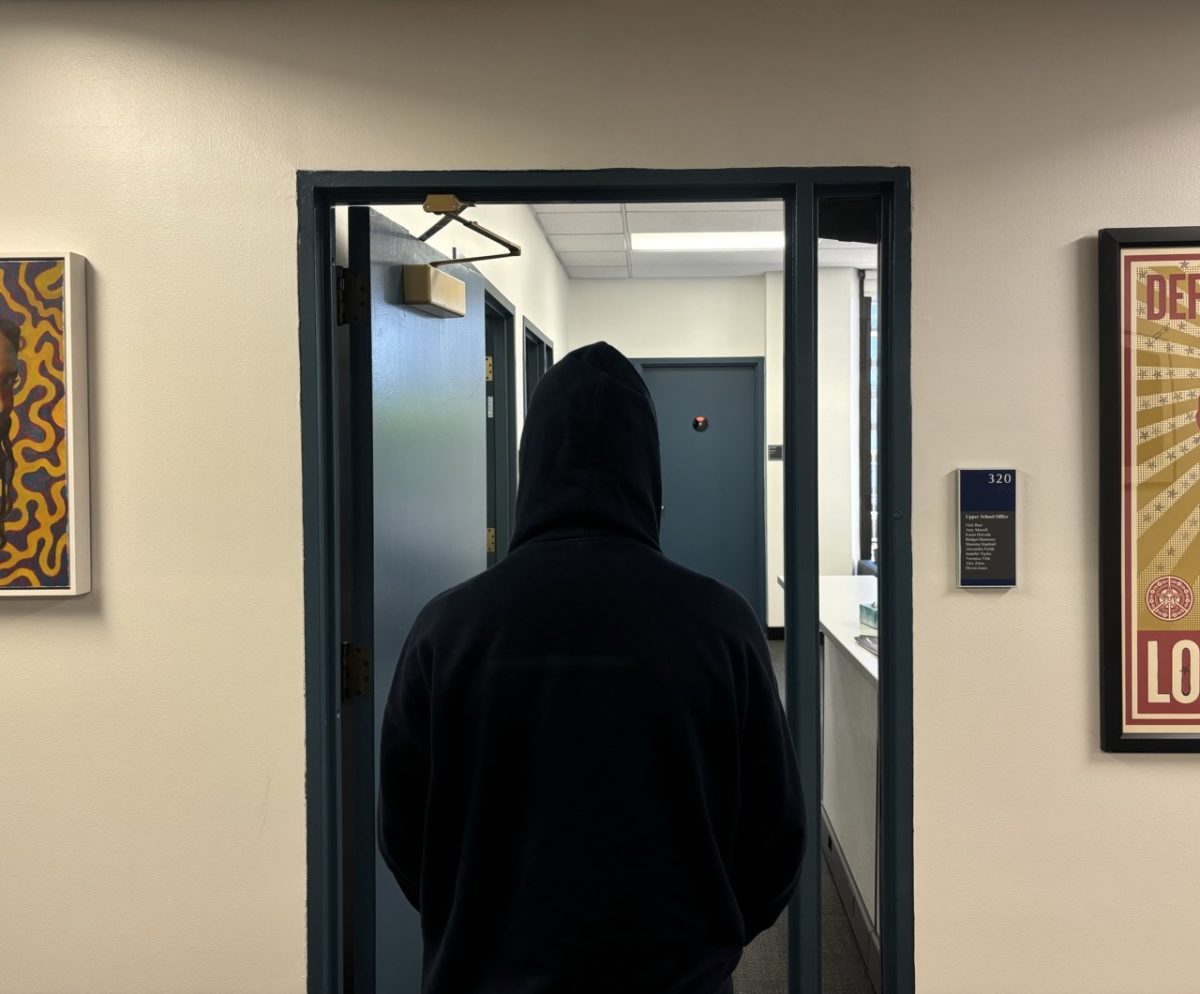

Venezuelan migrants pose for a photo outside of the 18th District Police Station.

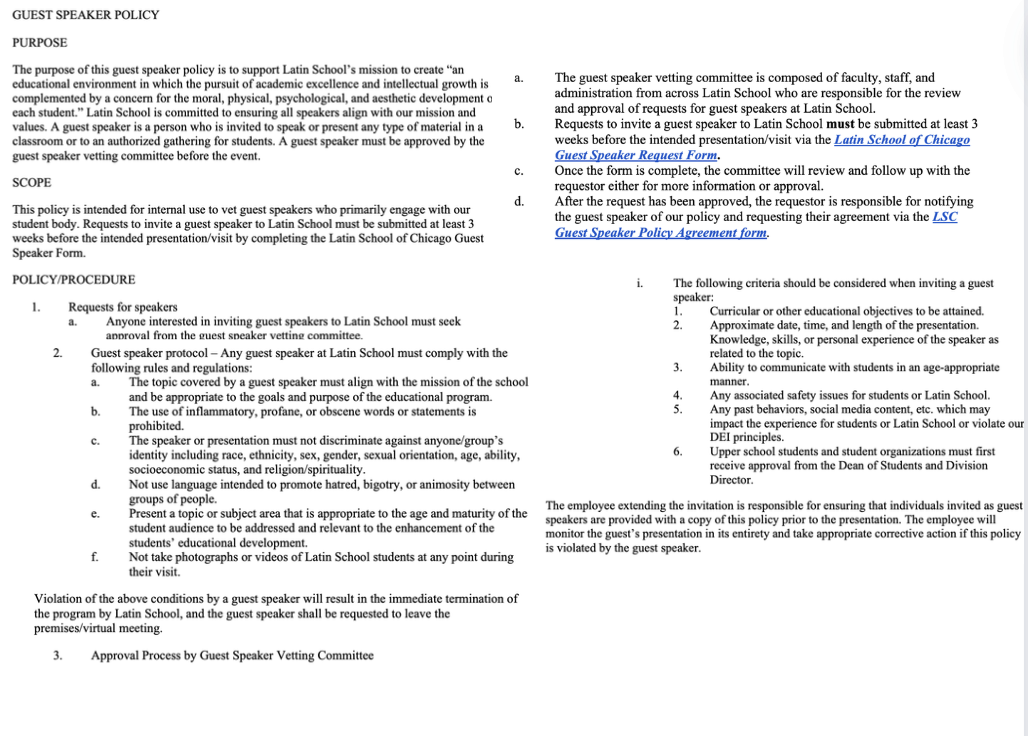

Disclaimer: This article contains quotations that were translated from another language and edited for clarity. In addition, for privacy reasons, The Forum is using only the first names of some of the people interviewed for this article.

The City of Chicago, historically known as a gateway for migrants, has once again become a forefront destination of refuge. Over the past year, the United States has experienced a significant surge in Southern border crossings. Now, more than 20,000 South American migrants have found sanctuary in Chicago, where their living conditions are subpar.

The majority of these migrants hail from Venezuela, a nation recently plagued by economic and humanitarian collapse. Coupled with what U.S. analysts deem an illegitimate democracy instituted by President Nicolás Maduro, the country’s situation has driven millions from their homes. Many of those Venezuelans journey to the United States as asylum seekers.

Yolis, a Venezuelan migrant living outside of a police center in Chicago, shared her experiences with The Forum.

“[I] came to the United States for its economy and ability to provide a better future for our children while also escaping the instability of Venezuela,” she said.

After traversing the U.S.-Mexico border, migrants are commonly sent to sanctuary cities, where officials are directed not to abide by national immigration laws. This allows for migrants, regardless of legal documentation, to receive humanitarian assistance and support, as well as potentially being able to apply for work permits.

Mauria, another asylum seeker from Venezuela, shared her experience prior to coming to the United States.

“[I] was fine, economically,” she said. “However, the U.S. just offered more sources of work, allowing [me] to search for a better future.”

Seven years ago, Mauria decided to immigrate from Venezuela—which she said was “unstable” at the time—to Ecuador. Yet, the allure of vast economic prospects and job opportunities in the United States prompted her to migrate. Mauria said she, like thousands of other migrants, “had to travel through a jungle” to enter the United States, only to be later sent to Chicago.

In Chicago, Mauria found a city known for its rich immigrant history. “It’s a part of our DNA—welcoming immigrants to build the city,” Upper School history teacher and long-time Chicago resident Ernesto Cruz said.

However, the widespread influx of migrants isn’t necessarily the result of open arms.

Across the United States, numerous city and state government officials have accused border states, particularly Texas under the direction of Gov. Greg Abbott, of directing an excessive and unnecessary influx of migrants toward Democratic states, with cities like Chicago told to prepare for over 25 buses of asylum seekers on any given day. Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker conveyed his frustration in a public statement.

“Governors and mayors from border states have shipped people to our state like cargo in a dehumanizing attempt to score political points,” he said.

Chicago residents are beginning to observe the consequences of the growing number of migrants as well.

Across the Chicagoland area, many police stations, airports, churches, and YMCAs have become the temporary (and crowded) homes for migrants.

Senior and Latin American Student Organization (LASO) Co-Head Carmen Quinones lives near a police station.

“Driving home, I’ll always see the [migrants] there, and it’s pretty crowded,” she said. “Once, I had to go into the police station, and the way [the migrants] were being treated [was] so dehumanizing.”

Cities like Chicago, which, due to their distance from the border, do not consistently receive unprecedented amounts of migrants, lack the necessary framework for situations like these. On the other hand, Southern border states such as Texas that regularly accept migrants have been able to implement the necessary infrastructure and legislation to better support their refugee population.

Essential elements of a functioning city, such as a supportive education system, have felt this lack of preparation, as well. Chicago Public School teachers have expressed their struggles to meet the needs of school-age migrants. Classrooms have grown excessively overcrowded, schools lack bilingual educators, and cannot provide sufficient counselors for essential mental and emotional support.

A lack of framework and resources, however, does not mean the city isn’t willing to try and mitigate this migrant crisis.

At the start of November, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson visited Washington, DC, to request more government assistance and funding for the crisis. In an interview earlier this month, he said “the federal government has to do more.”

Even locally, many feel that more could be done to assist the migrants.

“I think we’ve been doing as much as we can, but there definitely could have been more steps taken to ensure a smooth transition into the city,” junior Mel Butler said.

As migrants are experiencing an accumulation of anxieties, such as their plans for Chicago’s infamous winter, they are diverted from focusing on the essential steps to assimilation, making it difficult to integrate into Chicago’s community.

“The situation is not following the trajectory we expected it to,” Mauria said. “We can’t get a job or find any housing.”

Yolis echoed Mauria’s sentiment.

“We just want help to find housing so that we can focus on working,”she said.

Earlier this year, Chicago governmental leadership signed a $29 million contract calling for the sheltering of migrants in special winterized tents. Working in conjunction with a private company, the city plans to install 12-person “yurt-style” tents, which will include showers, toilets, and handwashing stations.

Mauria, however, explained that officials are failing to provide a definitive housing solution.

“They are trying to get us to a shelter but have not confirmed anything yet,” she said.

Yolis added that local leadership has told her to just “be patient and wait.”

Many migrants did not expect such a dismissive response from a sanctuary city.

“They’re being fed this image that life here is perfect [and] that once they get here, their [hardship] will be resolved,” junior and LASO Co-Head Andres DeMarco said.

“I heard this story from my parents, [who] spoke to an elderly woman,” he added. “When she told [her] story, she started crying. Her son … thought the situation was so bad back home that he wanted to bring her here. She walked all the way over [to the border], crossed the jungles, [and] almost died. But when she got here, she said nothing made that journey worth it.”

It has been many decades since this woman’s trek, though. Now, the willingness to provide aid and other resources is steadily increasing.

The Department of Homeland Security has begun working with the Chicago government to “assess the current migrant situation and identify ways that the city and the federal government can improve efficiencies and maximize resources,” ABC News reported.

In fact, as of October of 2023, Chicago has allocated over $350 million to tackling this migrant crisis—housing, basic humanitarian needs, and health care are all starting to be addressed.

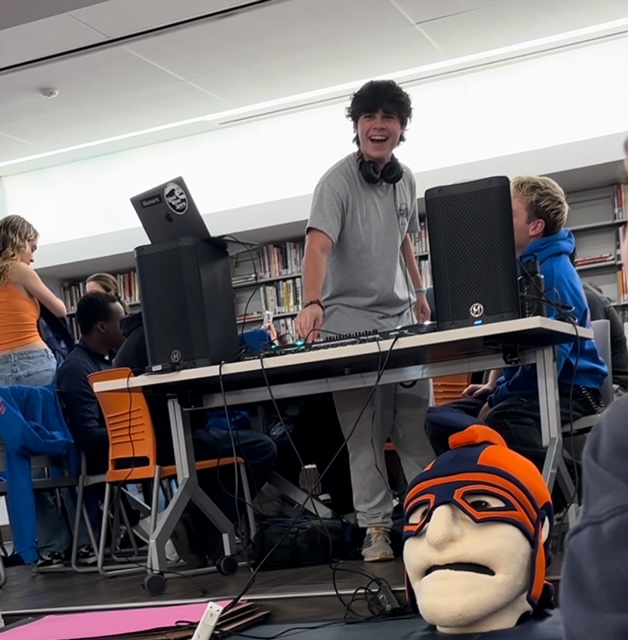

Latin has also been doing its part to help the migrants.

“The main thing I’ve done is pull together a group of teachers and staff,” Director of Community Engagement Tim Cronister said. “We met twice to plan the big picture, [which is] planning drives, making meals, and assemblies. I’m also working with the Parents Association. They have great community engagement coordination [and] been doing the drive and helping out with the winter clothes.”

He added, “We’ve decided to focus on the 18th Police District. We’ve probably made five or six meals for [migrants] starting in the summer.”

Many students are involved in Latin’s efforts. Mr. Cronister said, “There are some Middle School students I’m working with, and there’s a group of 10 high schoolers who want to help organize events. Student Service Learning Board (SSLB) has [also] initiated a bunch of those projects with me.”

The Latin community has provided support in this unprecedented situation, with students, faculty, and parents all continuing to chip in. However, the future for Chicago’s asylum seekers remains uncertain.

“We don’t necessarily want a better or worse situation,” Mauria said. “We just [want] a stable life, with the opportunity to work and be more like you—independent.”

Rohin Shah (’27) is a sophomore at Latin and is delighted to serve as news editor for The Forum. He hopes to become a proactive and investigative journalist,...

As a junior, Cherish could not be more excited for her third year on The Forum. Cherish looks forward to continuing to serve as a Sports Editor and relay...