Under the Radar Erasmus Society Is an Open Secret

Ann Longmore-Etheridge

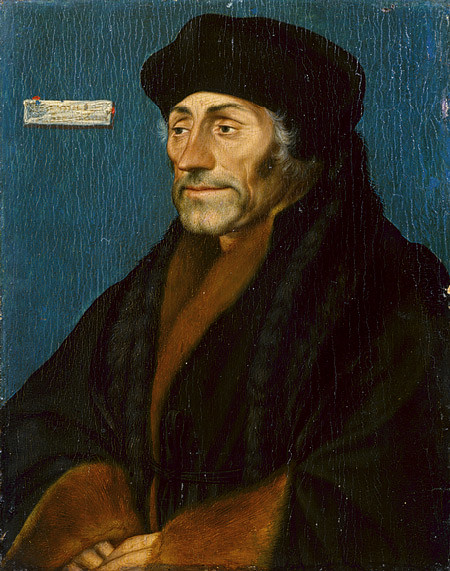

Photo of Desiderius Erasmus, the eponym of the Erasmus Society.

Latin’s Erasmus Society was founded six decades ago by the faculty as recognition for students who aren’t just engaged in their learning for the results—whether that be grades, college acceptances, or awards—but rather, those who pursue knowledge for the love of learning itself.

“The idea was really to honor people really engaging critically with a whole lot of different fields and showing that enthusiasm for learning in a way that faculty (and obviously also) classmates would notice immediately,” Director of Academic Initiatives and Upper School history teacher Ingrid Dorer-Fitzpatrick said.

Senior Zoe Larsen, a member of the Erasmus Society, said, “It gives me pride in knowing that my efforts to learn and be engaged pay off and that teachers notice it. It gives me satisfaction to know that students at Latin can be rewarded for their love of learning since most students base their academic success off of grades and comparing each other.”

Originally, the primary goal of the society was to distinguish between grade-motivated students and students who showcased a love of learning and intellectual curiosity.

Head of the Erasmus Society and Upper School history teacher Ernesto Cruz said, “I think one of the things that I’ve seen more and more of is that Latin students are really transactional learners.”

Transactional learners, namely the students primarily putting in the effort to receive an ‘A’ grade, go against the values of the eponym of the society, Desiderius Erasmus. A 16th-century humanist and free-thinking Catholic priest, Erasmus was interested in the studia humanitatis way of learning that’s focused on rhetoric, classical languages, and literature. In that time period, humanities wasn’t solely focused on history and English but was an umbrella term for all subjects and their interconnection. Erasmus believed that humans became uniquely human only through education, the foundation upon which true inquiry depends.

“[The idea was that students] are showing that enthusiasm for learning, and they are not saying, ‘Uh oh, this is now an X class; I’m totally shut down. I don’t care,’” Ms. Dorer said. “The idea would be that you do care, and you see the interconnection [between your classes].”

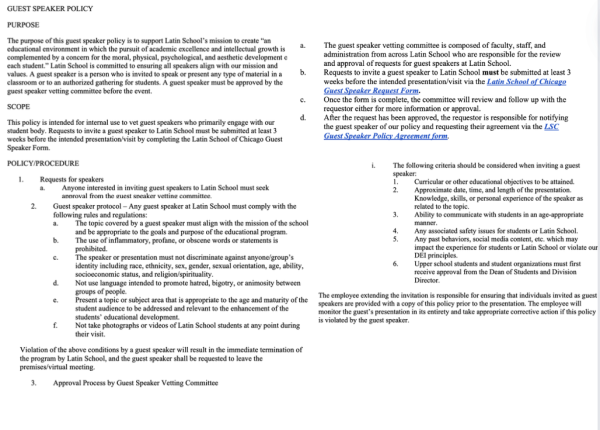

To become a member of Erasmus, a student must first be nominated by multiple teachers, and then, through a second form, must receive enough votes. The nominations happen before Project Week, and the voting takes place after spring break.

While the selection process is on teachers’ radars each spring, most students forget about Erasmus. Some don’t even know it exists.

“I did not know about the Erasmus Society before I got the email,” Erasmus member and senior Stephen Legendre said. “I actually had to go to my parents and have them explain what it was.”

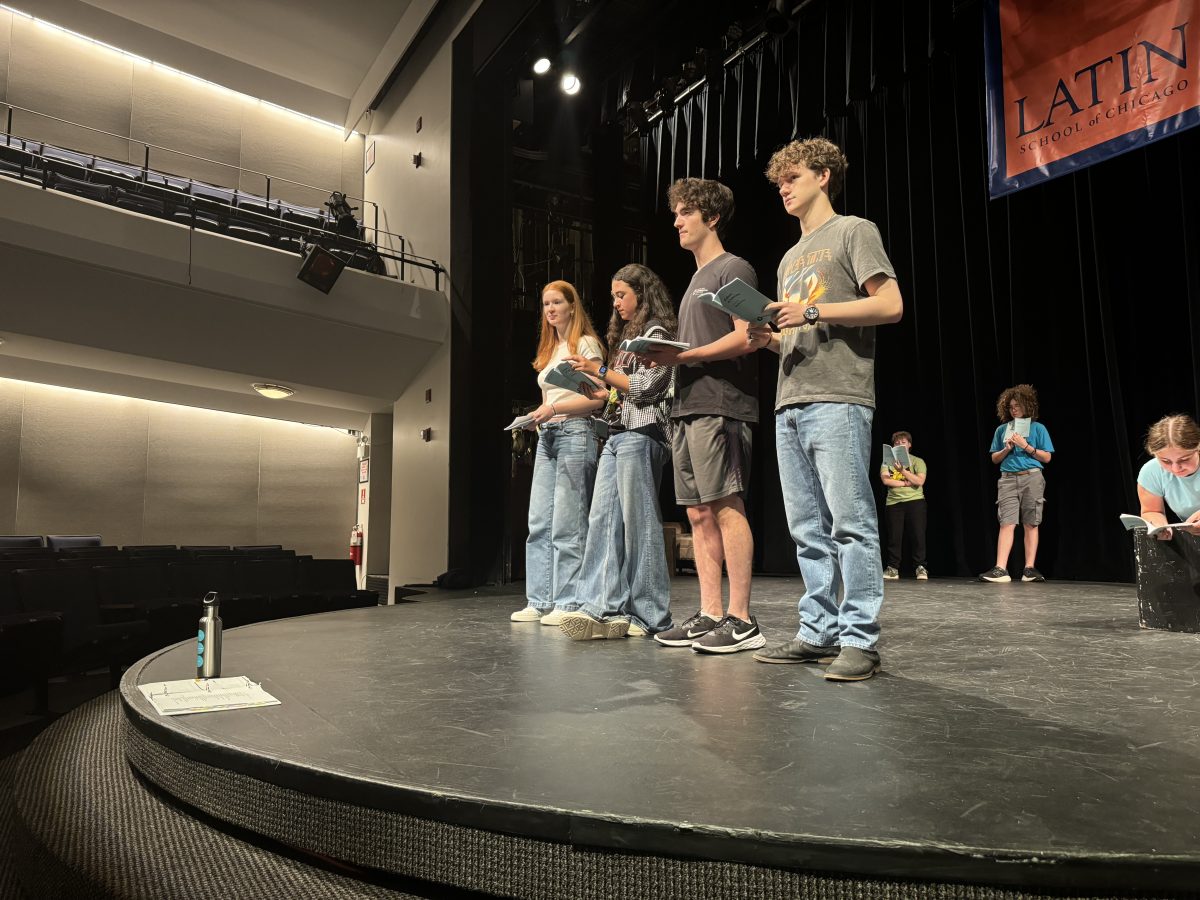

The Erasmus Society, unlike other honors societies, doesn’t meet regularly. At the end of each school year, they have an induction ceremony for new Erasmus members. In years past, the inductions were interactive. The inductees were asked to prepare a seminar on a topic of interest and share it with other society members.

“It wasn’t just a handing of certificates or engagement with the speaker,” Ms. Dorer said. “Students were engaging with each other and parents of other students.”

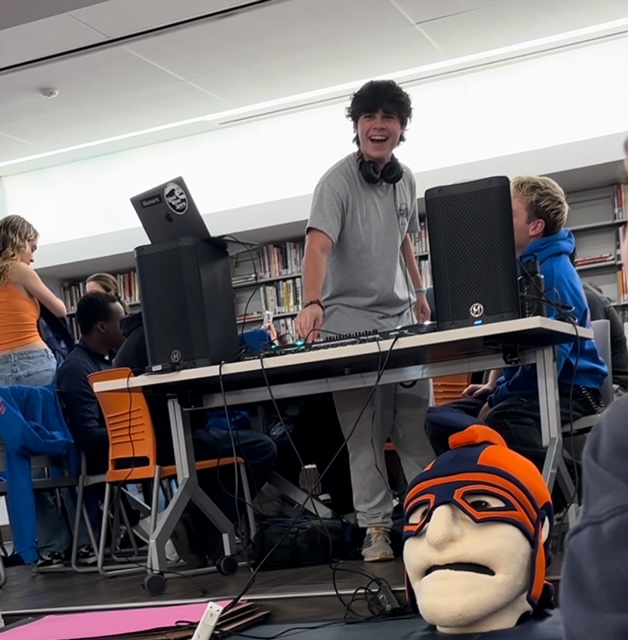

However, COVID brought an abrupt stop to the seminar tradition. Consequently, Mr. Cruz sought to implement a new tradition to honor students at the induction ceremony.

“COVID-19 really shifted what we had to do, so we shifted to something more virtually friendly,” Mr. Cruz said. “Folks seemed to really like the shift we made where we have a keynote speaker who tries to come in and talk about their intellectual journey and how they arrived to be the person they are today.”

Natalie Arora ('25) has been writing for The Forum since her freshman year and is thrilled to return this year as a Managing and Standards Editor. She...