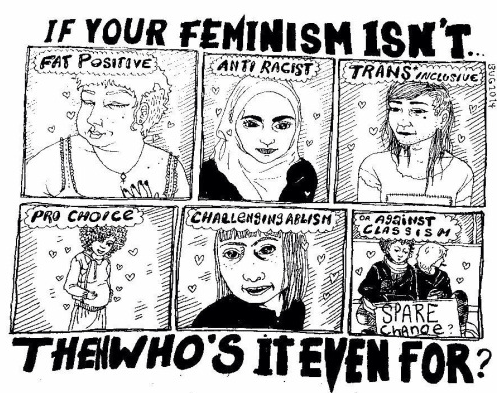

Anastasiya Varenytsya (Writer’s Note: To those in the community who do not identify as “feminists:” I think you will find some valuable information in this article that can pertain to you, and I hope that after reading, you can sympathize with the notion that intersectional feminism is indeed for everybody.) Intersectionality theory was first used in 1989 by black civil rights advocate and scholar Kimberelé Williams Crenshaw. In a legal opinion, Crenshaw ran across a case about a black woman, Emma DeGraffenreid, who had gone to court over racial and sexual discrimination, which she believed to be the reason why the auto company General Motors did not hire her. Labeling her case “legally inconsequential,” the court dismissed DeGraffenreid because there was evidence that General Motors did hire both blacks and women— but the court refused to recognize how General Motors’ employees were black men and white women. Here, the court was dealing with a black woman. In her TED Talk titled The Urgency of Intersectionality, Crenshaw explains how hearing the case and verdict “felt to [her] like injustice squared,” as there was no term that could describe a problem of double discrimination, and therefore, no distinct solution. She searched for a suitable name that could describe DeGraffenreid’s conflict, a conflict that illustrated standing equally vulnerable to both racial and sexual discrimination, so that justice could be served. Crenshaw agreed upon the term intersectionality: a social phenomena that describes a layering and an overlap of characteristics that are related to systems of oppression, discrimination, and domination. Intersectionality outlines the complex facets many individuals in America (let alone in the world) sometimes are unable to embrace because of systematic ignorance. I found intersectionality to be an important issue to bring forth to the entire Latin community because of January’s historic Women’s March on Washington and its sister marches. The theme — although not originally and only genuine in D.C. and Chicago — was intersectional feminism, where the goal to fight for all those marginalized based on their class, race, sexual orientation, gender, nationality, ethnicity, mental and physical ableness, professions, experiences, and all other forms of identity that make me me and you you was religiously earnest. To show the seriousness regarding inclusivity, the faces of the march had to be diverse to attract a broader audience. The idea of a march protesting Donald Trump’s election came from Teresa Shook, a Hawaiian woman who created a facebook group that attracted 10,000 R.S.V.P.s in a matter of eight hours. Bob Bland, the creator of the “Nasty Woman” t-shirts, also proposed a protest on facebook that eventually merged in collaboration with Shook. The two women called their group the Million Woman March, borrowed from the 1997 Million Woman March that was intended for “African American women to be self-determined.” As organizers joined Shook and Bland, many questioned the team of white women who the march was for — white sisters or all sisters? Once Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, and Carmen Perez joined the leadership team and changed the name to the Women’s March on Washington (a deliberate allusion to black activism), support for the march grew, but serious concerns still prevailed. American feminism from the grassroots level is racist, plain and simple: the women’s rights groups that sprouted during the Progressive Era excluded African American women from becoming members; suffragettes did not advocate for the voting rights of African American women (despite acquiring the legality to vote, they faced extreme obstacles when at the voting booth). It seems that black women have always marched behind white women, and some scholars even argue that a sisterhood between blacks and whites is an American fantasy, especially when considering the dynamics between the two groups during the time of slavery. So, it became essential for any sort of march to be a third-wave feminist movement that was intersectional, all-inclusive, and anti-white feminism (not anti-feminists-who-are-white, but anti-feminists-who-assert-white-supremacy). Why accuse Trump for going back 50 years, when we were about to do the same? Still, the movement received attack in the feminist circle. Some women complained that by focusing on intersectionality, the march would become an “intersectional torture chamber” that forced participants in “a grab-bag of competing victimhood narratives and individualist identities jostling for most-oppressed status.” Other women still felt uncomfortable to partake in the march and “feign solidarity with women who by and large did not have [their] back prior to November,” and there were others who found the pussy hats to be trans-exclusive. The fact that people, who the march was really intended for, were arguing and refuting the cause, confirmed for non-supporters that this was all a joke in the first place. Further, the disarray led to confusion about what the actual objective of the march was, causing people to ask questions like, “Is this anti-Trump? Pro-Woman? If I’m not a woman, can I join? What if I’m a woman who supported Trump? What if I’m a man who supported Trump but believe in pro-choice?” Well, despite being extremely hard to leave it out of the picture, the march’s intentions were not about Trump or Clinton, nor were they really, in retrospect. Yes, this was in response to Trump’s election. Yes, signs read Clinton’s slogans of “I’m Still With Her” and “Love Trumps Hate.” Yes, we chanted “We are the Popular Vote.” Yes, this was all so, so political. But the bigger message still stood: The Women’s March on Washington and its sister marches were the catalyst for redefining 21st century feminism to be intersectional and all-inclusive, a wake-up call for Americans to stand up against inequities that differ from their own, and proof that people actually care, listen, and want to make change. It was for the reason of intersectionality, and not the election, that we saw signs that read “Black Lives Matter,” “Refugees Welcome,” and “57 Degrees in Chicago On a January Day is Not Normal” swim alongside the pink sea of pussy hats, “My Body My Choice,” and “Women’s Rights are Human Rights.” And it is for the reason of intersectionality that feminism is a movement, led by women, that fights for so much more — for gay rights, for homeless rights, for refugee rights — than just my right to an abortion. So where does this leave us? Well, if you attended the march and believed in the purpose it served, you have an obligation to stand up against bigoted agendas that we may see in the next four years (or the next four days). If you call yourself a feminist, you have an obligation to redefine what feminism means and explain in any way you can that feminism is an issue that fights for the total equality of all. If you attend — or run— LAW, you have an obligation to push past your discomforts and begin truly making the space inclusive and safe. My first encounter with white feminism was freshman year at LAW: all of the heads were white, had been at Latin for a long time, and despite preaching to be open-minded, I felt uncomfortable talking about a lot of topics, like race and class, in that environment. The problem was not that they were white; the problem was that we lacked diversity in the leadership and, therefore, attracted one type of feminist. Regardless, I loved the community that LAW provided and decided to continue attending, as long as the club progressively strove for inclusivity. Come sophomore year, the club itself had diversified a bit, and we began talking about sisterhood and what it meant to be there for each other at all times; but we also were stuck in our comfort zones and focused on “non-controversial” topics, such as the impact of social media and classroom dynamics between boys and girls. Come this year, in addition to LAW, another women’s group is in the spotlight: Young Women of Color (YWOC). Created a few years back but recently remobilized, YWOC is an affinity group that holds lunches and events for Latin’s women of color to come together as a community and discuss issues and ideas, yet it still allows members room to join other affinity groups and clubs, like LAW (as YWOC continues to grow, contact Zyana Slade-Bridges, Maat Bates, or any members for more information). Despite coming together to talk about the election and other various topics, I wondered why create a YWOC when its purpose was what I thought LAW’s ought to be: did LAW not provide a safe, intersectional, and inclusive space for non-white women that led to the creation of basically a Latin’s Alliance for Women of Color? Whatever the reason, the thing not to do going forward is to discredit the existence of white feminism in our country and in our school. Remember, exit polls show that 52% of white women voted for Trump (his second-highest voter demographic), while 94% of black women voted for Clinton. Further, as 21st century feminists, we are responsible for validating and fighting against unjust struggles that may differ from our own — no more is our fight only about reproductive health and equal pay. If comfortable and able, support Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, and targeted religious groups by attending rallies and protests (I’m a facebook message/email away if you’d like a companion). If you cannot attend for whatever reason, you are able to support intersectional feminist groups through online means, obtaining information that can be shared with family, friends, and even “non-feminists.” If you are brave enough, respectfully call out people who are expressing any sort of exclusivity in their feminism, especially as we head forward into an administration that won based on anti-this and anti-that. Once we truly embrace what it means to be an intersectional feminist, we can successfully protect our most vulnerable and finally change the conversation from “We Can Do It” to “We Did It.”]]>

Categories:

More Than Just My Right to an Abortion

February 2, 2017

0

More to Discover