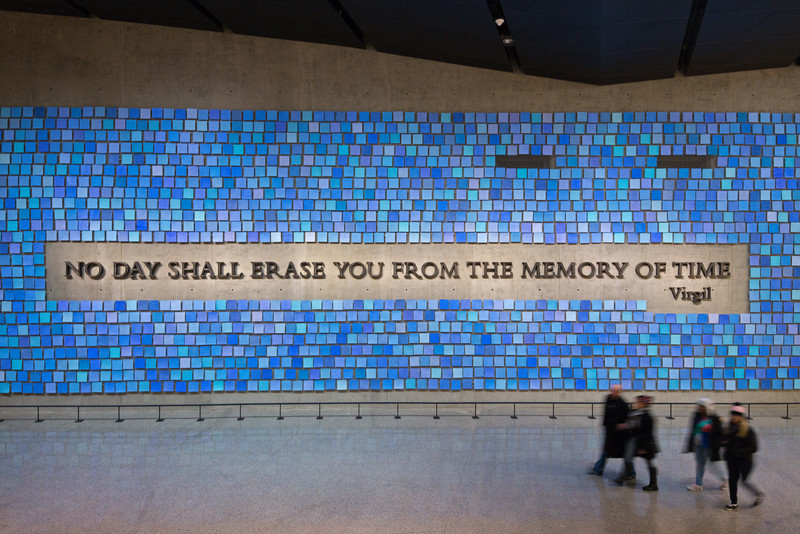

4 years ago our nation witnessed and lived through the attacks at the World Trade Center. Every adult has their own story about what happened to them on that day, and many of them will never forget that story. However it is different for the students of the Latin community who were just young children unable to comprehend, or even remember, that September day. This year, in honor of the 14th anniversary of 9/11, The Forum has collected stories from the adults in the Latin community. Every story shared is different and equally important. It is vital that we keep sharing these stories about 9/11; if not future generations may never realize the affect it had on our nation. “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” Virgal Brendan O’Toole: I lived in Williamsburg in Brooklyn and worked at Columbia University during 9/11, and I had a view of the WTC from my bedroom window. I was in the subway when the attacks started, and this was pre-smart phone, so I had no idea what was going on until I got to my office and saw dozens of emails and IMs about it. All the news websites were overwhelmed, so their front pages wouldn’t even load. My co-workers and I watched the second plane hit and both towers fall on TV in the lobby of the Columbia Business School. You had about a 2% chance of getting a phone call through, so everyone was repeatedly dialing their friends and family to try to figure out if they were safe. There were rumors throughout the day that other hijacked planes were still in the air, so we all tried to find places to go that we didn’t think would be targets of further crashes. We had no way to get back to our homes except by walking; the subways weren’t running and it was impossible to find a cab. There were fighter jets flying combat patrols over the city by late morning, which is why I still have minor panic attacks during the air and water show. The absence of any planes in the sky for the following three days was weird; you were used to seeing them above you all the time. There was a horrible smell, like burning plastic, over lower Manhattan and Brooklyn for a couple of weeks from the fires at ground zero. Everything downwind, including my apartment, got a thin coating of ash from that; I tried not to think about the pulverized buildings and cremated bodies we were wiping off every flat surface. When the mayor lifted the “stay home” order and we all went back to work, people would strike up conversations with strangers anywhere, the sidewalk, the subway, in restaurants and stores, talking about a mixture of rage, fear, and sadness. Lots of us introduced ourselves to neighbors we had seen but never talked to. Nearly all New Yorkers looked out for each other for a long while after that day. Pamela McCarthy: September 11th is a very vivid memory – I can remember what I was wearing, that the day was bright and warm, ugh. I was a junior at Quinnipiac, which is located just outside of New Haven, CT. I had a 930am class and as I was walking to get breakfast I remember thinking the campus was eerily quiet and there were few students in the cafeteria. I passed my professor, Dr. Norkus, who looked as though she had been crying. She explained what had happened and encouraged me to go back to my dorm. I rushed home, woke up my roommates, and turned on the T.V. We watched the second airplane crash into the south tower of the World Trade Center. I don’t even have words to describe how I felt. One of my roommate’s father worked in the world trade center – no one could get in touch with anyone up and down the east coast (perhaps other places too). The cell towers were receiving so much traffic they weren’t working. My roommate’s family ended up being fine but that wasn’t true of other friends of mine. Many professors and students lost friends and family members, including one girl who lost both her parents. Colin Lord: Today is, and always will be, a tough day for me. I’m a New Yorker, and I worked in the building right next to the world trade for a year between high school and college. On 9/11 I was just across the water from the World Trade, in Jersey City. My younger sister was in the army, my college roommate was NYPD and worked for the Mayor, and my best friend from high school worked right next to the World Trade Center. I remember watching the second plane flying into the building and immediately realizing “we were under attack”. I tried calling my family and didn’t get a call to go through until after noon. 9/11 was the most devastating day of my life, and I’ve lost family (dad) and friends to tragedy and illness. I still remember the jet planes flying over, national guard on the streets with rifles and the 24 hours of constant sirens. I remember sitting on the Jersey boardwalk watching the cloud of smoke (yes, even 12 hours later it was still a tower of smoke). It is a day I will never forget. Crazy thing, I was driving down the NJ Turnpike on the night of 9/10 and I was on the phone with my friend and I mentioned to her “how beautiful my city is” as I looked at downtown Manhattan. Elizabeth Pleshette: I was actually located catty-corner to the World Trade Center that day, working in downtown Manhattan. (Imagine a skyscraper on top of Chipotle that could look across at another on top of McDonald’s at Wells.) From the 26th floor I watched the first explosion and saw debris, office materials, paper and other objects fly from the point of the first plane’s impact. I am forever grateful to this day that I did not realize that people were also jumping, as my brain did not process that information at the time. None of us in the area knew it was a terrorist attack (all radio and news signals were blown out in lower Manhattan because their towers were on top of the WTC towers) and fear escalated after the second plane’s impact. That is when my coworkers and I decided to leave. I was fortunate not to be hurt and to have only minimal exposure to the pulverized building materials and smoke from the fires. Others, even on the street and the neighborhood were not as lucky. I eventually made it out of my building’s lobby after the first building collapsed and left the neighborhood. I had to walk five or six miles home. Cara Gallagher: I was working in Evanston that year and had just arrived at work shortly after 9AM on September 11th. The TV randomly happened to be on and tuned to The Today Show, which showed the first plane hitting the Twin Towers, so I saw the coverage almost immediately, in real time. I remember thinking what a massive screw up that the pilot must’ve made, there were so many mistakes: flying so low, flying into a building, etc. And then the second plane hit the next tower. In that moment I had one of the strangest feelings, which I don’t think has happened since, – that feeling that my brain just could not process or understand what my eyes saw. I was in total disbelief but never thought that these were “terrorist attacks.” I hadn’t grown up with a waking understanding that terrorism was a constant possibility; a real and living scary thing that lived in the corners of our metropolitan lives, like your generation unfortunately has. Typing that last sentence and writing this out actually gives me a profound sense of sadness because I feel like you guys were robbed of security. Anyway, I decided I wanted to go home around 11:00AM. Everybody was leaving to be with their families, so I was too. But to do this I had to get on the Red line and head into the city, which was unsafe at the time because there was still speculation about a possible attack on the Sears Tower. I stopped walking and thought “Am I crazy for potentially walking to my ultimate demise? Wouldn’t I be safer in the suburbs?” The answer in that moment to the latter was ultimately ‘yes,’ but everyone I loved was in the city and I would’ve rather risk my life and potentially perish with them than be alone. So I did, and it was the most terrifying, solemn El ride I’ve ever taken. But I made the right decision. David Marshall: 9/11 is something I can’t un-remember. I was teaching in Wilmington, Delaware at the time, and, because of a construction delay, our school was just opening that day. It was unusually cool and unusually blue and brilliant outside. It was my daughter’s first day of first grade. My son was starting fourth. As you can imagine, we all started the day with some exuberance, and my students—mostly ninth graders then—seemed excited to be back and finally get started. When the first plane hit, my department chair came by my room between classes to tell me, but he wasn’t sure if it was an accident. When the full story emerged, I was teaching. Like many people, I didn’t know what to do or think. Should I teach what I planned, pretending nothing had happened? As I was the cross-country coach, would we have practice as planned? Everything I looked forward to seemed empty. And Wilmington is close to NYC, close enough that many of my students had parents who worked there or other connections. Some students began breaking down in tears and were whisked away. Others left when their parents removed them. I wasn’t afraid of an attack but felt the world had shifted on its axis a bit. I made it to the end of the day, cancelled practice, picked up my children, and faced the same confusion. They weren’t really equipped to understand what happened, and I was drawn toward distracting them (and me) rather than facing a new reality. Television channels, all devoted to the disaster, offered no relief, so, as a “special treat” we watched a Disney movie on the VCR. I recall feeling a vague sense of guilt, as if I dishonored the dead by going on with life as normal. That feeling took weeks to abate. It was as if the brilliant sky was a lie, our national complacency a lie. Frank Tempone: I was teaching a 7th grade Language Arts class at a small school in western Massachusetts, and my principal, who was born in Canada, came into my classroom and said to me, “It seems as if someone has attacked your country.” New York was my home the first 25 years of my life, so I felt particularly terrified and angry. My youngest brother was a volunteer firefighter on Long Island that year, and I remember his anger and how he felt compelled to go the city and help. He wasn’t able to make it past the Midtown Tunnel. I shared his sentiment, though, of wanting to do something, anything, to help. My first son, Jack, was born in the spring of that year, so that added to my anxiety. My wife and I were a couple of years into our marriage, and now we’ve brought a baby into a world that seemed ridiculously unstable. I felt helpless, like there was really nothing I could do to protect my family. It’s generous of you to want my perspective, but I’m not sure the adults at Latin are the ones who suffered this tragedy. My son, his classmates, and the sophomores, juniors, and seniors of this school were either born into this new American anxiety, or they experienced it when they were two or three years old, during the most formative years of their lives. My son may not have known exactly what was happening, at five months old, but I’m positive he felt it. David Kim: I was visiting my friend at Princeton, flying into New Jersey after spending the weekend in Boston with my girlfriend (now my wife) on 9/10/2001. I got into Newark late, so when we finally got back to his place, we caught up for about an hour and made plans to wake up early and head into NYC for a day trip. I woke up groggy and discombobulated from the late night, turning on the TV to delay the inevitable morning routine. My friend and I watched his small 13” TV utterly stunned, knowing that the horror of what was unfolding was just a couple miles away across the Bay. Later that week I continued my east coast swing by taking the train to DC to visit my sister, who lived a mile away from the crippled Pentagon. Bridget Hennessy: I had a surprisingly close connection to what happened in NYC on 9/11 even though I was living in New Orleans. My college roommate was from just outside of NYC, and her father worked in the financial district right near the WTC towers. We were both sleeping that morning when her mother called our house frantically asking for Caroline. She couldn’t get in touch with her husband and the towers had just been crashed into. Luckily he was safe, but they knew many people who were not. The TV images are still very powerful, especially having someone who was so directly affected in my life. Come to think of it, I had just visited the WTC the summer before with her family in NYC. Mary Jane Baughman: The first thing I remember from that morning is a student arriving to Conversation class late. As she came in to class she announced that two planes had flown into the World Trade Center. At first we thought she was exaggerating. Eventually, we were all told to go to the theater for an assembly. There we were told about the attacks and students were encouraged to call parents if they wanted to. I vividly remember an advisee breaking down in tears as she had a family member who worked in the WTC. The next day or so my daughter got involved with other LS classmates to make ribbon pins to honor those who had lost their lives. There was lots of TV watching that night as we tried to understand what had happened. Billy Lombardo: Click here This article previously showed a quote from the September 11th Memorial and Museum; it has sense been brought to our attention that the context of that quote proves inappropriate and out of context for the events that occurred on September 11th. The museum has committed to this keeping this work of art as part of the memorial, and we at the Forum will keep as well as a way to discuss how the context of a quote is important when writing.

Here is Sarah Landis on the misuse of the quote:

This quote sounds like a thoughtful remembrance of that day’s victims, but in its original context it commemorates two Trojan warriors who are on a night raid, killing their sleeping enemies, and are only seen and killed in turn when one of them steals a shiny helmet which reflects the moonlight and draws hostile attention (Aeneid 9.314-449). What makes the quote extra inappropriate is that in the line immediately prior, the poet calls these two “lucky”: Fortunati ambo! si quid mea carmina possunt, nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo, Lucky both! If my poems are capable of anything, no day ever will remove you from remembering time (Latin text from TheLatinLibrary; translation mine) Those who died on 9/11 were a far cry from armed warriors killing their enemies in their sleep. Moreover, I don’t think anyone would call them lucky. Here’s an article from before the opening of the National September 11 Memorial Museum, examining the choice of quote. Here’s an article from April 2014. I visited the museum over Presidents’ Day weekend this year, and it was an emotional experience. But I found it especially troubling to stand in front of that enormous quote and think about the even more enormous disconnect between what it tries to say and what it actually says to anyone who recognizes it. I feel like that disconnect does a disservice to the memory of the lives it’s meant to honor. (And why? It seems so needless.)]]>