Frani O’Toole

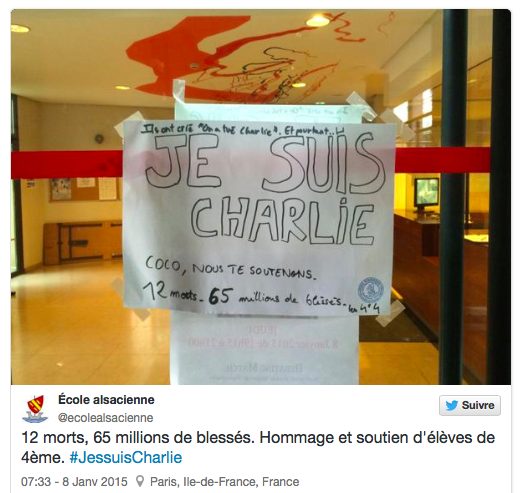

[caption id="attachment_4694" align="alignnone" width="300"] A flier posted on a door at L’Ecole Alsacienne.[/caption]

“Je Suis Charlie” as a refrain, hashtag, slogan, etc., has served to connect millions of people to the tragedy last week at Charlie Hebdo. In addition to that, Latin has a connection of its own; as part of the french exchange program, L’Ecole Alsacienne is Latin’s sister school in Paris. Looking at the Charlie Hebdo attack in the context of L’Ecole Alsacienne not only shrinks Latin’s degree of separation from the tragedy, it reminds us that schools are in a unique, if not particularly difficult, position in the wake of such events.

Last Wednesday’s attack, sadly, touched The Alsace School personally. Stéphane Charbonnier (“Charb”), the editorial director of the magazine and a victim of the shooting, had been scheduled to speak at The Alsace School for a panel on “Peut-on rire de tout” [Can you laugh at everything?] on March 27th. Charb had staunchly defended free speech throughout his career, and was quoted in The Atlantic as having said “I’m sorry for the people who are shocked when they read Charlie Hebdo. But let them save two euros fifty and not read it.” He had been invited to speak at the conference alongside Coco, an employee of the Alsace Schools and of Charlie Hebdo. Coco had been at the office the day of the attack, but had narrowly escaped harm.

Other alumni of L’Ecole Alsacienne are current employees of Charlie Hebdo, though none were injured. One parent of two daughters at the school, however, was shot.

On January 8th, the following day, the school published a report about increased vigilance—including a policy that prohibited vehicles from stopping, however briefly, in front of either of the school’s two entrances. All school trips were suspended. As suggested by French President François Hollande, the school observed a nationwide twelve minute silence. In their report, the administration of Rhe Alsace School also addressed the community at large:

En effet, ce drame nous touche tous, car il attaque les valeurs essentielles de notre République et de notre école, les droits de l’homme et du citoyen, la liberté de pensée, de conscience et de religion, le droit à la liberté d’opinion et d’expression.

[Indeed, this tragedy affects us all because it attacks the core values of our Republic and our school, the rights of man and citizen, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, the right to freedom of opinion and expression.]

Students at the school, which is located in downtown Paris, were quick to voice their own defense of free speech and Charlie Hebdo. My own french correspondent, Clara, and her sister Laurette posted photos from the protests.

Looking at the response of L’Ecole Alsacienne to the Charlie Hebdo tragedy raises questions of how a school should proceed in the aftermath of national tragedy. At Latin, September 11, 2001 happened fifteen days into the new school year. For nearly a month afterward, a group of seventh grade girls sold red, white, and blue ribbons to raise $2,500 for children in New York City. There were bake sales, a blood drive, and other fundraising efforts. Students penned hundreds of sympathy notes to families of NYC firefighters who had died, and nearly everyone in the school signed a giant American flag that they sent to a firehouse.

In cases like September 11, certain responses are automatic—the community mobilizes quickly, organizes a relief effort, sends aid. It’s the longterm response, however, that gets trickier. How exactly should a school go about encouraging/navigating/sustaining dialogue that is often sensitive and emotional? What does it mean to be a school in these types of situations? And, as perhaps a different question than the last one, what does it mean to be a community?

Here’s the answer the French Ministry of National Education came up with. In a letter to all schools, which was later published on L’Ecole Alsacienne’s website, the minister writes:

“Il appartient à l’Ecole de faire vivre et de transmettre les valeurs et les principes de la République. La République a confié à l’Ecole, dès son origine, la mission de former des citoyens, de transmettre les valeurs fondamentales de liberté, d’égalité, de fraternité et de laïcité.

L’Ecole de la République transmet aux élèves une culture commune de la tolérance mutuelle et du respect. Chaque élève y apprend à refuser l’intolérance, la haine, le racisme, et la violence sous toutes leurs formes.

L’Ecole éduque à la Liberté: la liberté de conscience, d’expression et de choix du sens que chacun donne à sa vie; l’ouverture aux autres et la tolérance réciproque.

L’Ecole éduque à l’Egalité et à la Fraternité en enseignant aux élèves qu’ils sont tous égaux. Elle leur permet d’en faire l’expérience en les accueillant tous sans aucune discrimination.”

[It is up to the school to live and transmit the values and principles of the Republic. The Republic has entrusted the School from the beginning a mission of training citizens to transmit the fundamental values of liberty, equality, fraternity and secularism.

The School of the Republic sends students a common culture of mutual tolerance and respect. Each student learns to reject intolerance, hatred, racism, and violence in all its forms.

The school educates for freedom: freedom of conscience, expression and choice of meaning everyone gives to his life; openness to others and mutual tolerance.

The school educates Equality and Fraternity by teaching students that they are all equal. It allows them to experience it by welcoming all without discrimination.]

Do you agree that this is the role of schools? What, if anything, does this list omit? Let us know in the comments below.]]>

A flier posted on a door at L’Ecole Alsacienne.[/caption]

“Je Suis Charlie” as a refrain, hashtag, slogan, etc., has served to connect millions of people to the tragedy last week at Charlie Hebdo. In addition to that, Latin has a connection of its own; as part of the french exchange program, L’Ecole Alsacienne is Latin’s sister school in Paris. Looking at the Charlie Hebdo attack in the context of L’Ecole Alsacienne not only shrinks Latin’s degree of separation from the tragedy, it reminds us that schools are in a unique, if not particularly difficult, position in the wake of such events.

Last Wednesday’s attack, sadly, touched The Alsace School personally. Stéphane Charbonnier (“Charb”), the editorial director of the magazine and a victim of the shooting, had been scheduled to speak at The Alsace School for a panel on “Peut-on rire de tout” [Can you laugh at everything?] on March 27th. Charb had staunchly defended free speech throughout his career, and was quoted in The Atlantic as having said “I’m sorry for the people who are shocked when they read Charlie Hebdo. But let them save two euros fifty and not read it.” He had been invited to speak at the conference alongside Coco, an employee of the Alsace Schools and of Charlie Hebdo. Coco had been at the office the day of the attack, but had narrowly escaped harm.

Other alumni of L’Ecole Alsacienne are current employees of Charlie Hebdo, though none were injured. One parent of two daughters at the school, however, was shot.

On January 8th, the following day, the school published a report about increased vigilance—including a policy that prohibited vehicles from stopping, however briefly, in front of either of the school’s two entrances. All school trips were suspended. As suggested by French President François Hollande, the school observed a nationwide twelve minute silence. In their report, the administration of Rhe Alsace School also addressed the community at large:

En effet, ce drame nous touche tous, car il attaque les valeurs essentielles de notre République et de notre école, les droits de l’homme et du citoyen, la liberté de pensée, de conscience et de religion, le droit à la liberté d’opinion et d’expression.

[Indeed, this tragedy affects us all because it attacks the core values of our Republic and our school, the rights of man and citizen, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, the right to freedom of opinion and expression.]

Students at the school, which is located in downtown Paris, were quick to voice their own defense of free speech and Charlie Hebdo. My own french correspondent, Clara, and her sister Laurette posted photos from the protests.

Looking at the response of L’Ecole Alsacienne to the Charlie Hebdo tragedy raises questions of how a school should proceed in the aftermath of national tragedy. At Latin, September 11, 2001 happened fifteen days into the new school year. For nearly a month afterward, a group of seventh grade girls sold red, white, and blue ribbons to raise $2,500 for children in New York City. There were bake sales, a blood drive, and other fundraising efforts. Students penned hundreds of sympathy notes to families of NYC firefighters who had died, and nearly everyone in the school signed a giant American flag that they sent to a firehouse.

In cases like September 11, certain responses are automatic—the community mobilizes quickly, organizes a relief effort, sends aid. It’s the longterm response, however, that gets trickier. How exactly should a school go about encouraging/navigating/sustaining dialogue that is often sensitive and emotional? What does it mean to be a school in these types of situations? And, as perhaps a different question than the last one, what does it mean to be a community?

Here’s the answer the French Ministry of National Education came up with. In a letter to all schools, which was later published on L’Ecole Alsacienne’s website, the minister writes:

“Il appartient à l’Ecole de faire vivre et de transmettre les valeurs et les principes de la République. La République a confié à l’Ecole, dès son origine, la mission de former des citoyens, de transmettre les valeurs fondamentales de liberté, d’égalité, de fraternité et de laïcité.

L’Ecole de la République transmet aux élèves une culture commune de la tolérance mutuelle et du respect. Chaque élève y apprend à refuser l’intolérance, la haine, le racisme, et la violence sous toutes leurs formes.

L’Ecole éduque à la Liberté: la liberté de conscience, d’expression et de choix du sens que chacun donne à sa vie; l’ouverture aux autres et la tolérance réciproque.

L’Ecole éduque à l’Egalité et à la Fraternité en enseignant aux élèves qu’ils sont tous égaux. Elle leur permet d’en faire l’expérience en les accueillant tous sans aucune discrimination.”

[It is up to the school to live and transmit the values and principles of the Republic. The Republic has entrusted the School from the beginning a mission of training citizens to transmit the fundamental values of liberty, equality, fraternity and secularism.

The School of the Republic sends students a common culture of mutual tolerance and respect. Each student learns to reject intolerance, hatred, racism, and violence in all its forms.

The school educates for freedom: freedom of conscience, expression and choice of meaning everyone gives to his life; openness to others and mutual tolerance.

The school educates Equality and Fraternity by teaching students that they are all equal. It allows them to experience it by welcoming all without discrimination.]

Do you agree that this is the role of schools? What, if anything, does this list omit? Let us know in the comments below.]]>

Categories:

Charlie Hebdo: Latin and L’Ecole Alsacienne

January 15, 2015

0

More to Discover