College Athletes Collect Coveted Compensation

New name, image, and likeness policies mean college athletes can profit off themselves

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled last year in National College Athletic Association (NCAA) v. Alston that college athletes can now take on name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals. In short, they can profit off of themselves. However, only a year after the decision was released, key questions are still up in the air—what do these new policies mean for collegiate sports? And what do they mean for athletes?

NIL deals allow businesses to feature athletes in commercials, ads, public appearances, and more—shoe campaigns and Gatorade endorsements are famous examples. Appearances come with compensation for participants, a novel way for collegiate athletes to make money.

Historically, the only compensation these students could receive for their athletic career was scholarships, but in the past year, several athletes have jumped at the opportunity to collaborate with brands and companies. Some regulations, like the fact that athletes’ earnings cannot depend on what school they go to or how well they do in their sport, still apply, but the NCAA’s policies have become far less restrictive.

Even only a year into the policies’ lifespan, many athletes have greatly benefited from the money they’ve received from NIL deals. Senior and committed Harvard University track and field athlete Alice Mihas said, “Maybe [an athlete’s] family is struggling at home, and them going to college is taking away from them helping their family.”

Roughly 43 percent of Division I athletes do not receive athletics aid, meaning that many are left to rely on academic and need-based scholarships. Moreover, the large time commitment required of college athletes may prevent them from earning other sources of income. Alice said, “College athletes work so hard—it’s basically like you have to do a job on top of being a student.” In fact, in terms of time commitment, that scenario is generally accurate; official NCAA guidelines do not allow athletes to train for more than 20 hours a week, although a 2015 lawsuit cited data from a 2011 NCAA study that found the average player in certain sports trained and played more than 40 hours per week—the equivalent of a full-time job.

On the other hand, some critics of the NIL ruling are concerned that the new regulations could lead students to pick larger schools just for their potential to help the athlete earn more money. Although the regulations are designed to limit school-based sponsorships, some schools may still have more resources available, like assistance reviewing contracts or marketing and business classes, that would help athletes find NIL deals.

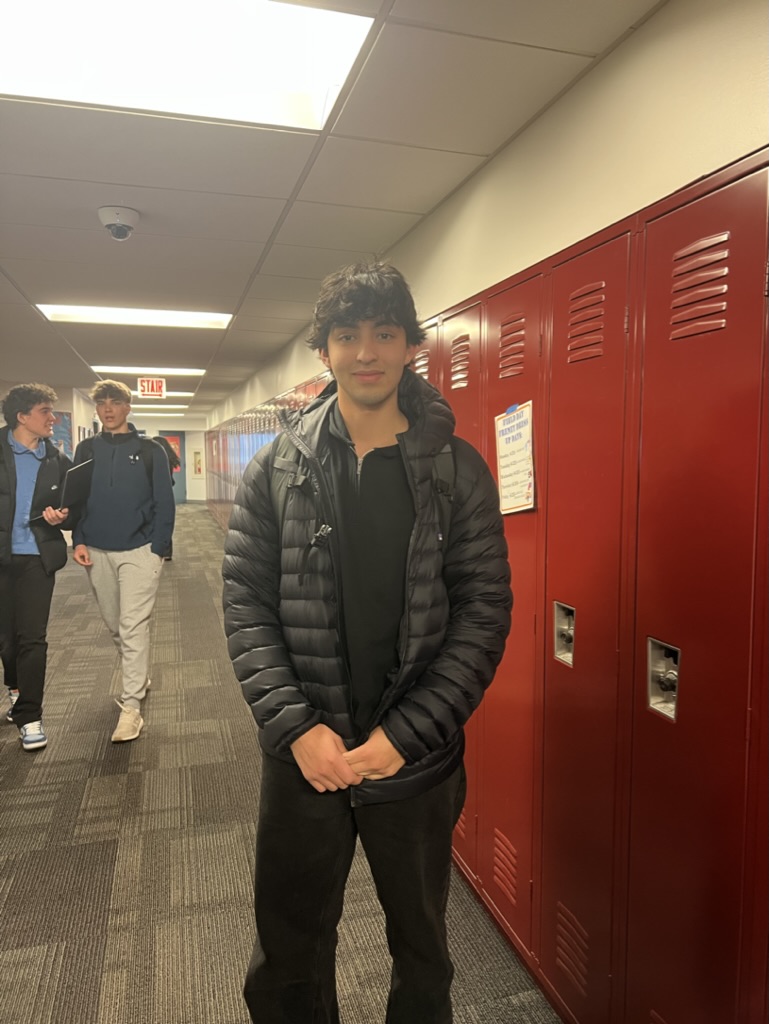

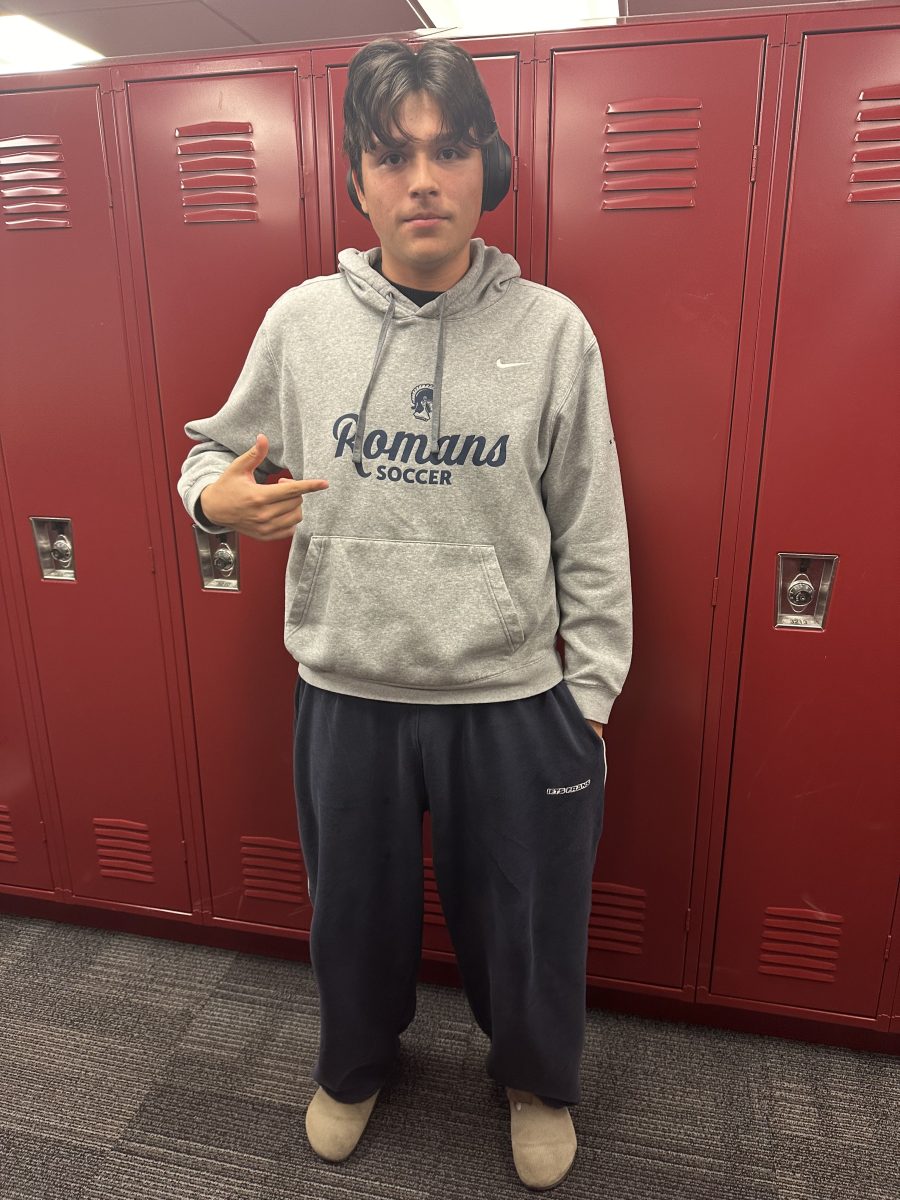

However, those same schools likely already had access to resources that could make them more appealing to potential recruits. Senior and committed University of Michigan track and cross country athlete Akili Parekh said, “Those big schools already could give scholarships and already had better facilities and better everything,” he said. “Which is very similar to just giving them an extra thousand dollars a month.”

In addition, those larger schools are more likely to have profitable athletics programs, though nationally, such programs are few and far between. The median revenue generated at Division I athletics programs was about $20 million less than their median expenses as of 2021. Many supporters of the NIL ruling would argue that paying athletes “makes sense for sports that are bringing in a lot of money for the school,” as Alice put it, but restricting sponsorships to schools that generate revenue from athletics would further increase pressure on athletes to choose larger universities.

Notably, limiting sports sponsorships to athletes on profitable teams might deepen already present gender biases in sports. Nationally, female sports often get less attention than their male counterparts, as is the case at Latin. Conversely, giving athletes from lesser-known programs the chance to get NIL deals could, as senior and committed University of New Hampshire field hockey player Carly Warms said, “empower female athletes because they can finally have proper representation.”

Furthermore, only brands have to profit off the athletes they work with in order for an NIL deal to be successful, not the universities those athletes are playing for. Akili said, “For the smaller athletes who don’t bring in as much money as football or other things, they can get small sponsorships with recovery brands or power bars or something, and that could really help people.”

As for how Latin athletes feel about the ruling, many are excited by the prospect of potential NIL deals. “I feel like it should have been done sooner,” Akili said.

Carly said, “College athletes put in so much time and effort and money to get recruited, so being able to get paid back for that is a really amazing idea.”

College athletic recruitment is known for being a demanding process. Officially, athletes can begin to communicate with coaches and receive verbal offers June 15 of the summer before their junior year, but for many, the path to college athletics starts far earlier. “I started my recruiting process in eighth grade,” Carly said. “It takes a lot of mental strength.”

Recruitment is not the only time when this strength is needed; a passion for their sport is a common link in the stories of athletes from Latin and beyond, a quality well worth cherishing. Carly said, “You have to just keep pushing because you love the sport.”

Scarlet Gitelson (‘26) is delighted to be serving as one of this year’s Managing and Standards Editors. Using her writing, she seeks to promote connection...