Ashna Satpathy, Staff Reporter

In 1978 Ingrid Dorer Fitzpatrick created one of the most notable classes at Latin to date: Nazi Mind. Nazi Mind’s rigorous curriculum includes studying how the Nazi’s came to power, the atrocities of their actions, and their impact. What differentiates this class from any other are two components: a detailed look at the psyche of those involved in the Nazi Regime and how one allows themselves to commit acts of evil, and the second, manifesting this knowledge into a 12-hour simulation of the 1946 Nuremberg Trials in a Chicago Daley Center courtroom. Students are assigned roles and must commit to lengthy and meticulous readings of the actual indictments presented at the trial while also writing their cases.

This entire process is no doubt a demanding undertaking, and many wonder if they get the credit they deserve for taking such a class. Latin has an honors track for Math and Science that begins freshman year, but why isn’t Nazi Mind an honors course considering its difficulty? Do students stronger in the humanities get recognized for their talents and the work they put in in the same way strong STEM students are?

Dr. June, one co-teacher of Nazi Mind, laid out the basic premise behind why the course is not an honors class: “Whenever we have a standard track class versus an honors or AP track, there needs to be some kind of placement involved in that, and with the way we have the tenth grade classes set up, we want to give students as much freedom as possible to pick and choose the classes they are interested in, so we just don’t have a placement process for tenth grade, and because of that we don’t have honors classes for tenth grade. The idea also is that [the classes] are all very different, so to standardize what would be honors or not is just not something that’s been done.”

Sophomore Charlie Williams, who is currently taking the class, agrees that placement could pose issues: “A concern that came up with it being an honors class is that then you would have to be placed into it.” She explains how requiring placement could make for a less dynamic classroom environment. She says, “I feel like then you kind of create a divide in the classroom setting in terms of who would be in the honors class and who would not, and Nazi Mind is a class where the different perspectives are really valued and that could be something that is taken away if it’s an honors class.”

Dr. June explained the implications of giving all students a variety of classes to choose from: “What is hard is always relative and a matter of perspective. What might be hard for some in Nazi Mind is really easy for others, whereas a person who can do really well in Nazi Mind might take Global Art and Culture and find that very difficult just because of the different skills and understandings that are involved in them.” Dr. June outlined more nuances behind a variety of courses: “There’s a big advantage to letting students self-select which classes they want because everyone takes Global Studies in ninth grade and everyone is going to take a version of US History in eleventh grade, so this gives an opportunity for kids to pick and choose and follow their own interests. I don’t think anybody comes into Nazi Mind not knowing what to expect.”

After taking the class last year, junior Marianne Mihas agrees that students who sign up for the class are prepared to work hard. She says that while “anyone can be in Nazi Mind as it’s not selective, I think students that choose to take Nazi Mind are choosing to take a harder course.” Sophomore Mckenna Fellows, who is currently enrolled in the class, agreed, saying “Compared to other history classes, it’s a very different setting and dynamic and more is expected of you. It’s just that in order to take it you have to be really willing to take on all of the work.”

Mr. Cruz, the other co-teacher of Nazi Mind, explains what this decision looked like: “There was just an agreement that we wouldn’t have honors tenth grade classes, that we would save that for eleventh grade, and that’s really the only grade where we make the honors distinction mostly because there’s a belief that we don’t want to be gatekeeping experiences from students because I think that leads to inequity issues that we don’t want to be involved in. We don’t want to be involved in leaving kids out of experiences that if you’re here, you have the ability to rise up to.”

While Dr. June recognized that there is no honors benefit to Nazi Mind, he offered an alternative benefit: “The flip side is, if it is different, if you do work differently and it does feel like you’re working harder, then I would argue that that’s a benefit in and of itself that you’ve perhaps gotten to do some different things than you would have in another class. The benefit might not show up in one’s transcript per se, but it’s still there in other ways.”

Many may not realize that in a couple of years, honors classes won’t matter. “If we keep going with this mastery transcript, there’s not even going to be an honors benefit for a GPA because we’re not going to have GPA’s. It’s all going to be about mastering different standards. This is a problem from a decade ago that isn’t worth fixing for the next decade,” explained Dr. June. He says that the question of making Nazi Mind an honors class has been discussed before and they concluded that the advantages show up in different ways, stating, “long term, there will be some evident advantages if you are working above and beyond in certain classes. As we move to the mastery transcript where everything is based on different objectives and how we’re assessing your progression on those objectives, there will be times in certain classes, for example the trial in Nazi Mind, where you can really show your command in the humanities in a way that will be reported on your final mastery transcript. Even in my two classes, Middle East and Nazi Mind—they’re similar, but you have the chance to do certain things in Nazi Mind that you have the chance to do in Middle East. So, my main goal with moving towards standard-based assessment and hopefully getting to the mastery transcript is to make sure that students’ advancement in their skills in the humanities is showing up beyond just an A on the transcript.”

Mr. Cruz further explains the implications of the lack of honors on a transcript. He says, “Doing things for the purpose of a transcript defeats the point of being at a school like Latin. The strength of the transcript is the name at the top of the transcript, not an honors designation that really, in the grand scheme of things, means very little. I think putting honors in humanities particularly feeds and perpetuates inequities in the educational system in a city like Chicago. We’re not going to disenfranchise students who are trying to be here to be better.”

Unlike Honors United States History and American Civilization, which have two years of prior humanities experience to base placements off of, Nazi Mind could only draw from ninth grade work in deciding placements. “I’m uncomfortable with acting like the ninth grade is enough data to determine tenth-grade placement. After ninth and tenth, we have a better picture of where students are and what they’re capable of,” Mr. Cruz says.

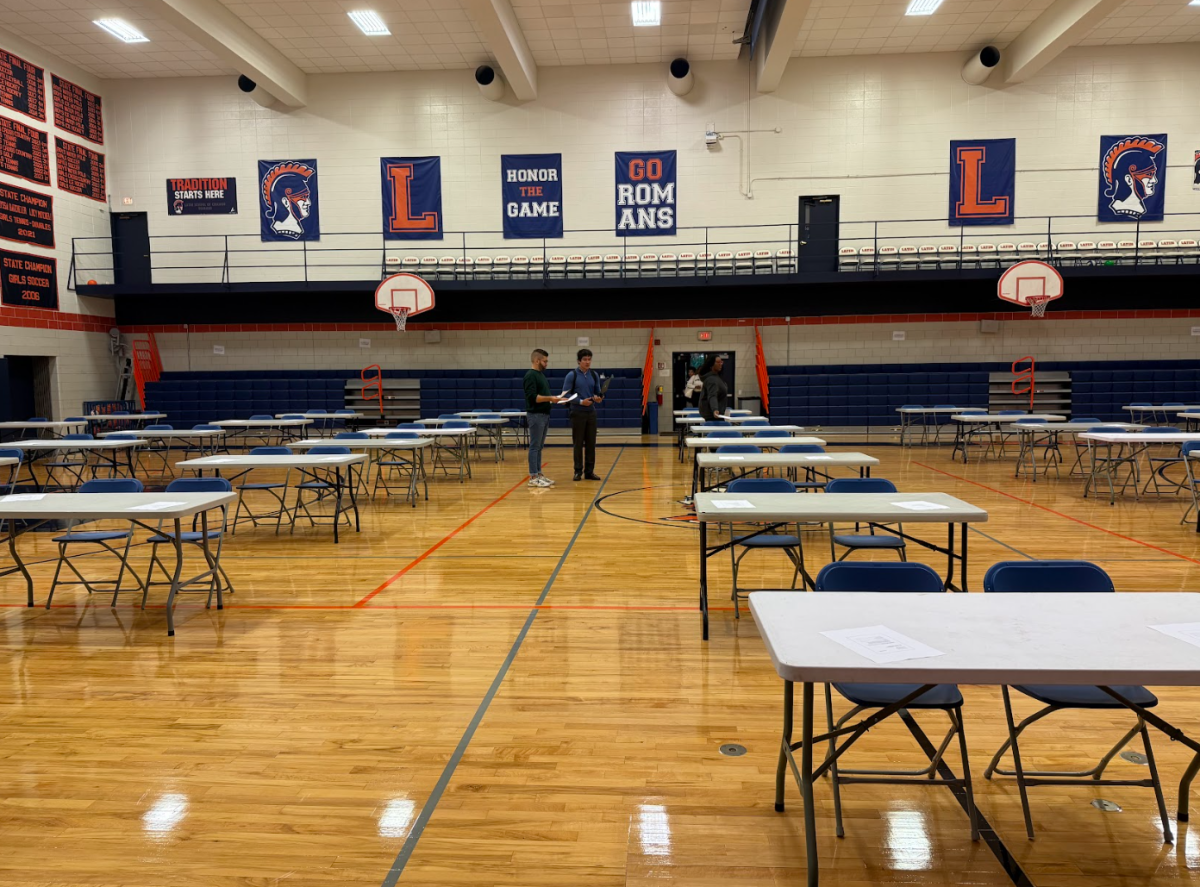

Additionally, Mr. Cruz explains, “there’s an appeals process for honors classes because there’s a larger capacity. We can add more HUSH sections and we can add another American Civilization class; there’s a capacity for that. There are 36 seats in Nazi Mind and no amount of wishing is going to up the number of seats because every 6 additional seats is another two hours of trial time. The next number is 42, which means we have a minimum 14-hour trial, which is unrealistic.”

The bottom line is that making Nazi Mind an honors course would have more drawbacks than benefits, on all sides. “We’re going to discourage kids who are good enough from thinking they’re good enough, and we’re going to have some difficult conversations with kids who believe themselves to be good enough, who are in fact not as good as they think. Neither of those things should happen. I shouldn’t be telling a fifteen-year-old ‘you’re not as good as you think.’ No, I should be giving them the opportunity to be as good as they believe they are, and letting them decide how good they are,” says Mr. Cruz.

Taking this question into a more expansive view, the relevance of making Nazi Mind an honors class is expiring. As Latin moves towards standard-based grading, there is really no point in making such a change that would not have much relevance in the future. In tenth grade, students have the opportunity to explore their interests, and they shouldn’t be hindered by not being good enough to explore what they are interested in. Taking a harder class is only an opportunity for academic growth, and the benefits of such a challenge will show through in the future through improved skills.

But, of course, one can also argue that there is an inequity between those stronger in the humanities and those stronger in STEM. It makes sense for students that are significantly better in English and history courses to be frustrated with a lack of credit for these strengths, unlike their math and science oriented peers that are given the honors title next to the classes that help exemplify their strengths.

Standard-based grading, however, may be able to ease these issues and allow for nuances in student’s learning to show through: “it’s not going to be about one class being honors or not, it’s going to be about the different opportunities you have to show your mastery in different things, and some classes might provide more opportunities than others, but we’re hoping that through some other changes that are happening, that we’re excited about, the question you’re asking won’t need to be asked in a couple of years,” says Dr. June.

Categories:

Why Nazi Mind Is Not an Honors Course

November 1, 2019

2

0

More to Discover

Lulu Ruggierl • Nov 4, 2019 at 7:36 pm

As someone who took Nazi Mind, I found that everyone brought their best and was enjoyed in the material, so there wasn’t a strong divide of who was willing to work hard and who wasn’t. Great article, ashna!!

Robert Igbokwe • Nov 3, 2019 at 6:51 pm

Insightful article, Ashna!! 🙂 🙂 I think what I loved most about 10th grade history was the ability to truly pursue my interests without worrying about how my academic choices will look like on my transcript. I don’t know what it was like to be in Nazi Mind, but I know that the history classes I did take challenged me in new and rewarding ways, and opened my mind to issues and ideas I’d never considered before. 🙂