Banned for Life: Why Gay Men Can’t Donate Blood

November 17, 2016

Before donating blood, each donor must complete a survey answering a series of questions. In 1977, a survey question appeared that today, every donor still has to answer. “From 1977 to the present,” it says, “have you had sexual contact with another male, even once?”

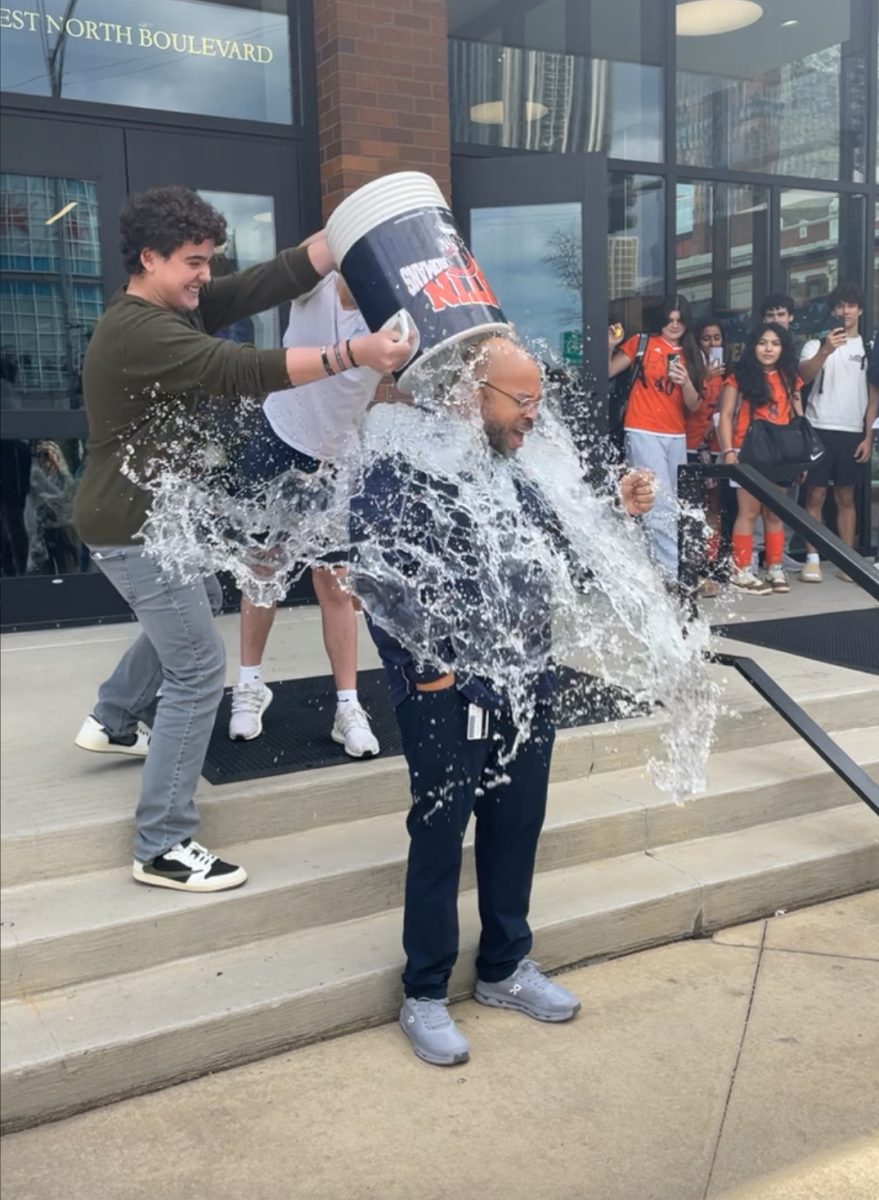

After I donated blood at Latin’s blood drive, I discussed my experience—not a very pleasant one, but that’s besides the point—with a very close, openly gay teacher of mine. I promptly asked if he was giving blood, and he responded, “I can’t,” as if he had been programmed to say that all his life. If you are a gay man and answer that survey question honestly, you are placed in a lifetime ban, unable to donate blood.

According to the FDA, gay men are considered in the highest-risk blood-donor category. Others in the category are intravenous drug users and those who have spent more than five years in a country with mad cow disease. The fear is that those who have had gay sex or IV drug administration are more likely to have HIV and or Hepatitis—which, according to the statistics, is true. Roughly half of the people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are gay men, even though gay men only make up four percent of the nation’s population.

The CDC recently reported that, “63 percent of new HIV infections occur around MSM— the agency’s shorthand for ‘Men Who Have Sex With Men.’” In 1985, eight years after the ban was set in place, the FDA discovered a way to test blood and plasma for traces of the HIV virus.

But then why is there still a ban? Why can someone who just received a tattoo or had sex with a prostitute (granted they wait 12 months) give blood, while gay men cannot? Prior to 1999, when a faster and more accurate test was developed, the HIV tests were made to detect high levels of antibodies in the blood. But, if one is infected with the HIV virus, there was believed to be a 45-day window where these antibodies were too low to be detected, so the blood tests were not always accurate.

In 1999, the test was changed to look for the actual virus, not just the antibodies that fight against it. Although it may seem like a far-fetched idea to be able to find a tiny virus throughout your whole bloodstream, professor Attila Lorenz Ph.D. says that, “[we] send million of tiny robots into [your body] to find that [virus] for you.” Within seven to ten days, the blood sample can be accurately tested with 99.9% accuracy and deemed HIV negative or positive. So it’s understandable that someone who has had unsafe sex within the past two weeks should be turned away, but is a lifetime ban still justifiable?

“It takes a week or two to diagnose HIV, not a lifetime.”

–Professor Attila Lorincz, Ph.D.

But according to the FDA, odds may seem slim to the general public; however, it is a risk that they are not willing to take. The fear is that there could be false negatives in the test. However, blood banks wish to defer to a one year “window period.”

The standoff between the FDA and blood banks is nothing new. In general, blood banks are strong advocates for gay donors. Using blood shortages as an example, Steven Kleinman, a medical advisor for the AABB (American Associations of Blood Banks), said that, “The lifetime deferral for MSM is medically and scientifically unwarranted.”

In 2010 and once again in 2012, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services for Blood Safety and Availability Advisory Committee voted against changing the FDA policy. At first, I was utterly confused and saw this as blatant discrimination against a group of people. Somewhat ignorantly, I neglected to consider the data.

Even after I understood the facts, I had a hard time justifying the lifetime ban. These rules, although backed up by numbers, may still be rooted in our subconscious prejudice as a country. So while some gay men are fighting for the right to donate, many have accepted their position and understand that sometimes the statistics win.

tkendrick • Nov 18, 2016 at 1:08 pm

Thanks for this piece, Lauren! I’ll be honest, I think it’s all just a way to circumvent my donating of blood, because ultimately, if you get some Kendrick blood, you are subject to an unexplainable new obsession with Kelly Clarkson, and let’s be honest. That shouldn’t be forced upon anyone, even if they are in need of some blood. 😎