Frani O’Toole & Henry Pollock

It took an article in the school newspaper to bury Phillips Andover Academy in a controversy that many of its students didn’t even believe existed: gender inequality. What began as a furious Letter to the Editor, following the election of yet another male student president at Andover, quickly spread to the pages of The New York Times, and raised questions across the country about the condition of gender equality in our schools. The writers of the article criticized the student body’s “casual attitude” towards gender equality, and condemned what it called the “omnipresent ‘but there isn’t a gender problem at this school.’” Like at Andover, Latin students tend to question any arguments that the school has yet to guarantee equal opportunity to both sexes; out of twenty-one people who were surveyed, only two students believed that Latin could not boast true gender equality. While many students may be confident in Latin’s encouragement of men and women alike, Mr. O’Toole reminds us that “there’s a difference between equal opportunity and equal outcome.”

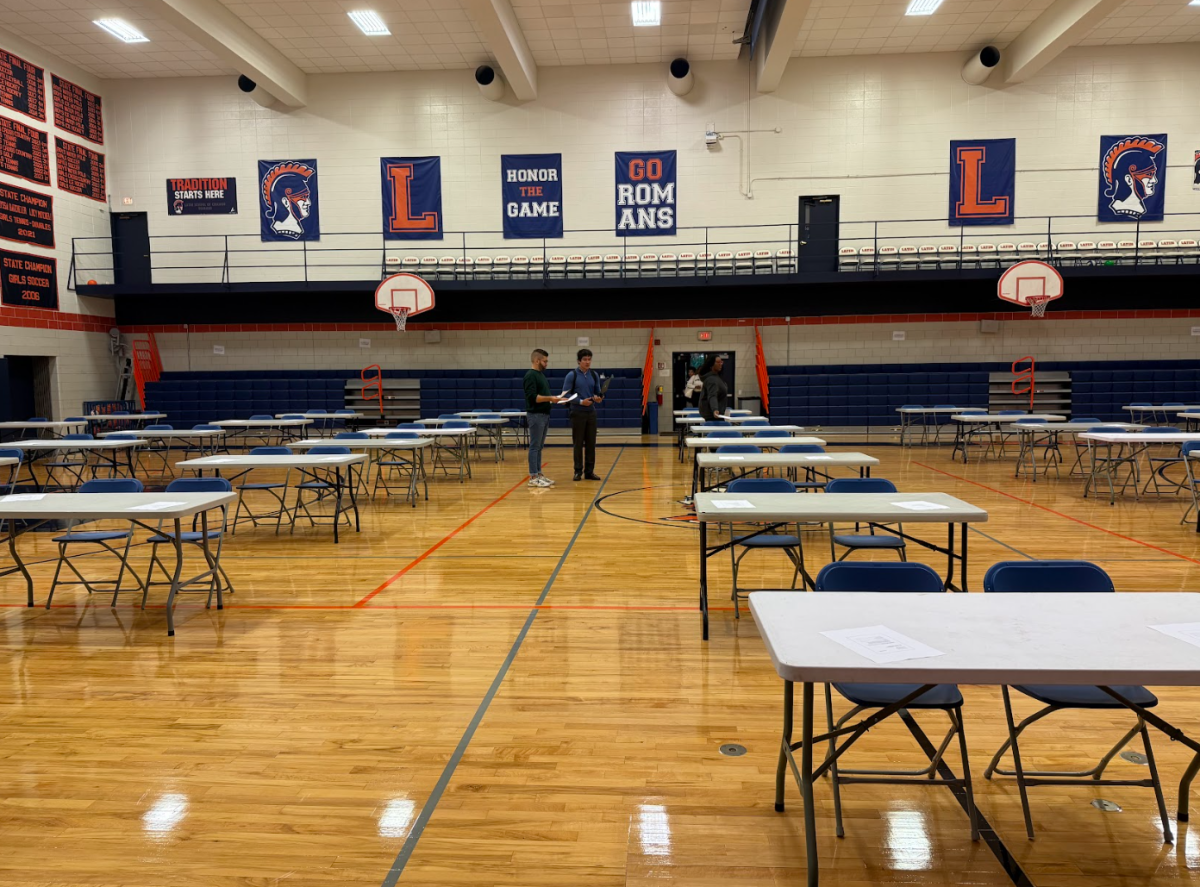

With student elections igniting the gender debate at Phillips Andover Academy, Latin’s upcoming student elections may be a good place to start. Since 1953 — the year Latin became co-educational — 62 males have filled Latin’s top student leadership position of Junior/Senior prefect. Over the same period of time there have been 24 females. That means 28% of students elected have been women: needless to say, equality would be 50%. Even in the past five years, there have been two female prefects and six males. While other factors certainly determine a candidate’s electability aside from their gender, the disparity in the numbers is worth noting.

What if, however, the inequity was limited to the top leadership of Latin’s student government? That is, at least, what the numbers suggest. Of the 88 club leadership positions, 47 of them are held by women compared to 41 by men. This balance more accurately reflects the fact that 55% of Latin students are women, and it is what one would expect the ratio of prefects to be as well. So why does Latin’s student government reflect such inequity? Senior Kevin Ward expressed his concern about Latin students falling victim to common stereotypes of a “good leader” when he said that “many Latin students, like a majority of the world, view men as better leaders while they stereotype women with qualities that they have deemed counterproductive in a leadership positions – for example, decision-making based on emotional response. I’m not saying Latin students necessarily believe this of their peers, but because they often see this portrayal of men and women in greater roles of leadership, it’s difficult for them to elect women to positions of power.” Kevin’s viewpoint suggests the need for action to combat what may be Latin’s inadvertent perpetuation of these gender-based stereotypes. While to most it is obvious that women and men are equally qualified to be leaders (see Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, Hillary Clinton and John Kerry), a significant minority of people still maintain the idea men are better leaders. To Kevin and many like him, the world — Latin included — has failed to stay committed to gender equality, and needs to redouble its efforts to achieve it.

Our focus on student government as an example of unequal gender “outcome” is similar to a larger trend in which analysts focus on political, high-profile cases of gender inequity. In reality, the issue extends far beyond that particular field and applies to every career, particularly in areas Latin students tend to gravitate towards. Latin encourages us to fulfill our full potential, but at the same time some of the strongest gender inequality can be found on those high-achieving paths. In top-level management, it is estimated that men account for around 75% of the highest-ranking positions. As of the beginning of this year, 3.6% of the Fortune 500 chiefs are women, and analysts are calling that number a “milestone.” How we act in high school is preparation for real-world application. If we fail to address gender inequality on a small-scale, how will we respond when we encounter it later on? While we may not have a “glass ceiling” –a term in economics for the barrier that prevents women from ascending the corporate ladder– above our heads at Latin, its existence is as significant for us and our futures as it is for those in the workforce right now.

We go to a school where more than half of the student body and over 52% of our classroom faculty is female. In contrast to schools like Andover, we cannot complain of a shortage of powerful, strong female role models in our community. While the New York Times said that Andover’s “paucity of girls in high-profile positions […] leaves younger students with few role models and discourages them from even trying for the top,” Latin’s club leadership and strong representation of women make up for the “paucity” of girls we may find in the junior/senior prefect position. We are also a community that has been unafraid to address the issue of gender inequality, like we have with bullying, hazing, or hate speech, and can easily boast significant progress. To many at Latin, we have come so far as to reach a point of diminishing returns –it is becoming harder to make even little amounts of progress. Maybe, if the efforts to promote equality at Latin are not producing much yield, the school should try helping other communities become more equal. Or maybe there is still work to be done at Latin. Either way, equality can only be reached when every person, every school, every community is cognizant of the problem and fighting to fix it. And everyone has equal reason to do so: equality is worth fighting for.

bhennessy • May 6, 2013 at 4:39 pm

Hey team! Thanks to Frani and Henry for this article – it’s well written, thoughtful, and timely as Stud Gov elections are around the corner. I thought it would be worth mentioning that the breakdown for Stud Gov candidates in terms of sex is this: out of 24 candidates, only 7 are women. Chew on that, peeps!

Mary Jane • May 3, 2013 at 7:59 pm

Wow, this thread got kind of salty. I think that there are issues for both men and women. But given that the men affected by the issues didn’t really create them themselves, I don’t think it’s super fair to blame them for them. I don’t know what to say about girls being percieved as more engaged in class, but I know I’ve read studies about girls speaking more than guys, period, so maybe girls do participate more? Though this is rank speculation. And I think the prom ask thing (in general the asking out thing) cuts both ways. For a lot of guys, unless they ask a girl out (or to prom) they won’t get a date. I, as a girl, havr the privilege of not needing to summon any courage to get a date. But then again if a girl asked a guy out she runs the risk of being considered desperate, so… It cuts both ways.

botoole • May 3, 2013 at 1:39 pm

Both men and women bear equal responsibility for establishing or perpetuating norms for gender-based behaviors. However, men hold power in our society and the world (we are the hegemonic group). Saying a male-dominated system is misogynist does not mean that all men are individually misogynist. It simply means that a given tradition, policy, or law creates an unequal and unfair power relationship biased against females. I absolutely agree that the girls at Latin also need to seriously question their own actions in perpetuating negative gendered behavior.

It can be very difficult to separate one’s own personal experience from societal norms, but that’s what we have to do to objectively understand the function of these power dynamics. There are ongoing structural and behavioral biases in our society against women (wage gap, rape culture), against minorities (redlining, drug conviction sentencing, segregated proms), and against LGBT people (employment discrimination), among many other categories. This does not mean that all straight white men are racist, sexist, or homophobic. It also does not mean that there are no black lesbian racists. The fight against the ERA, after all, was led by a woman!

It is not a personal fault of those currently living that there has been thousands of years of bias against women. However, I believe it is our duty to do whatever we can to reverse as much of the legacies of discrimination as possible while we are living our own lives. Does that mean men *collectively* should have less power in the future? Absolutely; as a class we have far too much power relative to women. Does it mean *individual* men should be penalized relative to women? Absolutely not. We should be treating everyone close to equally. There are certainly some aspects of society which discriminate against men (child custody, paternity leave policies, e.g.), but those systems were created by men, so that’s a self-inflicted wound!

These discussions are great! I hope we have opportunities to continue them.

jmartin • May 2, 2013 at 11:08 pm

I just wanted to point out that there are a majority of women in the class of 2014’s top level math class– and it’s not close. It’s 4 to 7 or something like that male to female. Also, in terms of prom askings, it is expected that men will make an ask and the average man will fall under harsher criticism from his peers, both male and female, if he did not ask. If women are so critical of the misogynistic prom askings, perhaps they should ask their dates or tell their dates not to ask them instead of pressuring their date to do a grand public gesture. I would also like to point out that I think that “gender equality” is different than “gender difference.” Men and women have taken different types of leadership positions. Also, while this article mentions the fact that the man is typically regarded as having more leadership qualities, another article I read points out that women are perceived as more engaged in the classroom. This would perhaps partially explain why (Correct me if I’m wrong) women receive better grades then men.

It is certainly an interesting debate and the data clearly does show that Men have the upper hand in student government, and this needs to change. But there are certainly other areas dominated by women.

William • May 2, 2013 at 10:48 pm

That’s a bold statement statement to say that asking a girl to prom represents a hatred of women. Next time I’m in an elevator with other people I’ll flip a coin to determine whether I should wait as not to perpetuate gender roles. Also, high school can be emasculating enough without listening to why their gender is and has been abusive. I get that you’re trying to get us to question tradition, but sometimes traditions take on new meanings. I highly doubt Charlie’s song was seen by anyone as the first step towards enslavement. Anyway let’s not look for ways to be offended. What is way more dangerous than stereotypes is censorship and that is the direction our school is heading in. Gathering should be an open time for students to with as they feel appropriate. While I didn’t like the fact that I had to sit through a long song, many enjoyed it and I respect his right to perform.

botoole • May 2, 2013 at 11:11 am

Frani and Henry, thank you for this thoughtful article.

The damaging perpetuation of gender stereotypes pervades Latin culture, as we are very much part of the society around us. Just consider prom “asks”. Although it seems like a small thing, continuing the tradition of boys publicly asking girls is misogynist. It perpetuates the idea that girls are to be passive in relationships (which is itself a consequence of the long legal tradition viewing women as property), while boys are expected to be the aggressor. It’s not difficult to draw a line from this tradition to a male reporter asking Secretary of State Hillary Clinton what clothing designer she prefers.

For two years, we have offered an ISP on the history of feminism, and we have had only one boy show any interest in it. I think that’s a bigger problem than the sex ratio of the MV Calc class.

William • May 2, 2013 at 8:43 am

Peter makes a good point about the math, but I think it’s not something that Latin alone can fix. I think it’s cultural. We’ve all heard boys are good at math girls are good at english, but that is just false. There is no reason both can’t be good at both. I agree with parts of the article, but I think you’re looking for sexism against women and not the reverse. Why is Latin 55% women? Why is a majority of club leaders being women considered strong representation and not sexism? There are in fact slightly more young men than young women. Women are now more likely to graduate high school and attend college. Is this something to celebrate? I’m not trying to sound sexist, but there are no institutional obstacles to women attaining power. The beautiful thing about capitalism is that the just changes will eventually happen. Eventually there will be enough corporations that realize that women make as good executives as men and change will happen. Until then, let individual boys and girls climb to success and let’s deal with sexism against both on a case by case basis.

pwiggin • May 1, 2013 at 10:42 pm

I agree with MJ that equality of opportunity and equality of outcome are NOT the same, and equality of outcome is not always something worth striving for. Here, the problem is way bigger than student government––way bigger than Latin, actually. Economic and political leaders (top-level management and (student) government) have to see themselves as strong and independent. Hillary Clinton is a perfect example. Unfortunately, young girls are often taught to “fit in” rather than to seek independence and self-reliance. It’s not about voter bias: I would bet that if 28% of representatives were female, 25-30% of the candidates were female. It’s just that society teaches girls to avoid autonomous positions.

On another note, girls are consistently weaker than guys at math, at Latin and elsewhere. My Multivariable Calc class is 70% male, which I think is typical. Any thoughts on why girls drop out of the top-level math classes at Latin? Is it something Latin can work to correct? (It’s not a biological difference, certainly.)

Mary Jane • May 1, 2013 at 8:56 pm

This is well written, but I can’t help but disagree with some of your reasoning.

Firstly, the average of all the data from 1953 onward in terms of gender of prefects is fascinating, but I think to include it implying that it is highly relevant to the present day is misleading. More relevant would be the last ten to twenty years, given that in the last sixty years vast changes in gender relations have occurred. Simply put, whether or not Latin had gender equality in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s has little bearing on the state of the school now- the school has had ample time to change.

Also, I think (and boy will I sound like a conservative here) that equality of opportunity and equality of outcome are not the same thing. Furthermore, I’d be interested to see the ratio of females to males *running* for these positions, as if more boys run, it is almost an inevitability that more boys will be elected.

On a larger note, I agree that these issues are important, and I enjoyed your article. Cool stuff, guys.

bsulliva • May 1, 2013 at 8:55 pm

I’d be interested to see the leadership numbers from around 2000-2013 or the club leadership positions from 1953. I feel like it has been for the most part even in recent years.