Anti-LGBTQ+ Language on the Rise at Latin

Words like “zesty” have entered student vernacular as an alternative way of refencing queerness in a disparaging way.

Over the past several months, LGBTQ+ Affinity leaders and students say they have seen an uptick in anti-LGBTQ+ language throughout the Latin community.

“There have been concrete examples of people using slurs, for example, or people calling things gay in a pejorative kind of way,” LGBTQ+ Affinity adviser and Upper School Computer Science Department Chair Ash Hansberry said. “I’ve [also] had students just in my office chatting with me, saying not so specifically but talking about a general feeling, like ‘I feel like I’ve heard people in the hallways calling things gay more.’”

Senior and LGBTQ+ Affinity head Stephen Legendre agreed with Mx. Hansberry’s sentiment. “It’s mostly a general sense, especially from the freshman class, that queer people are not respected,” they said. “Around the community, we are seeing an increase in homophobic stigma.”

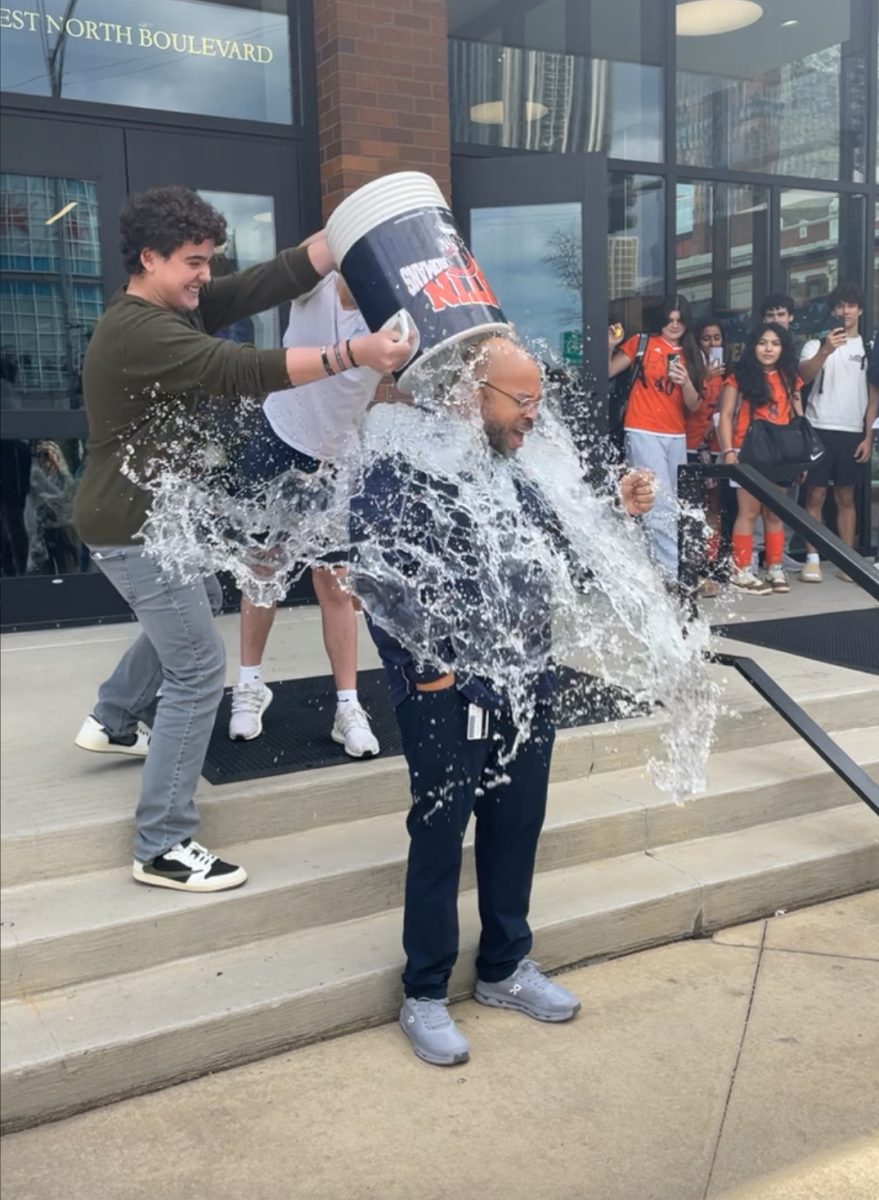

Administrators are hearing these reports as well. Upper School Director Nick Baer said, “I absolutely believe Mx. Hansberry and the affinity group when they say that that’s what they’re experiencing.”

However, there are also administrators who have not heard about these incidents thus far. Head of School Thomas Hagerman said, “The LGBT community is very close to my heart personally and professionally.” Yet he noted, “I’m not hearing a lot of homophobic stuff out there.”

Either way, advocates say that these events must be taken seriously. Mx. Hansberry said, “While it’s not numerical data, if students are feeling like they’re hearing something enough to come and talk to me about it, we need to do something about that.”

These reports, and actions taken to address them, are not just coming from faculty—Stephen and senior Mikayla Smey shared a presentation with Upper School students in October about the uptick they were seeing. Mikayla was inspired to create such a resource after observing anti-LGBTQ+ language being used around the school. “I had already heard earlier in the week that somebody had been [calling people gay as an insult],” she said.

Moreover, students are not the only community members who have been encouraged to educate themselves regarding this topic. In fact, faculty have received materials designed to help them better understand the issue and support their students.

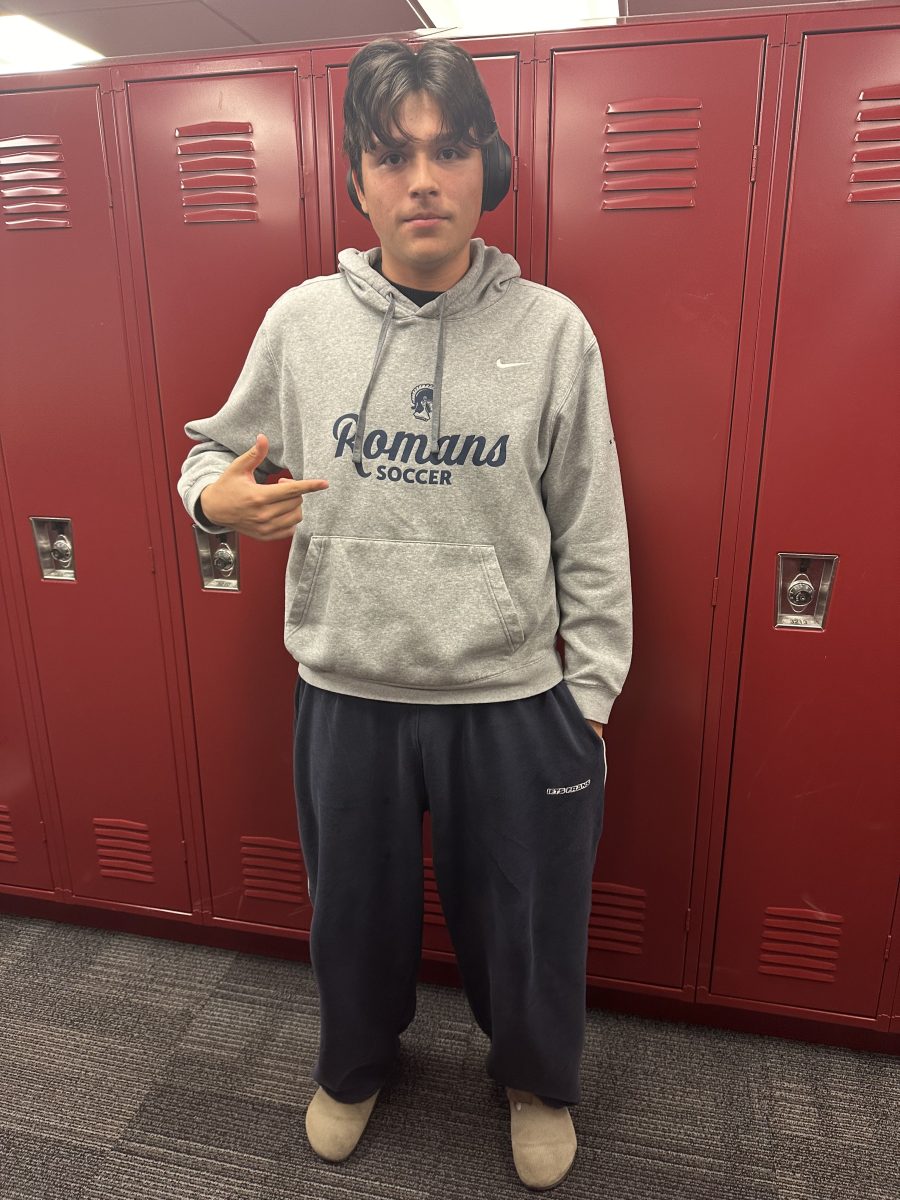

“One of the things [the LGBTQ+ Affinity advisors] told us is [that] there’s some things that faculty may be missing just because they are not fluent in the current lingo,” Upper School English teacher and DEI Curriculum Coordinator Brandon Woods said. Faculty met during one of their divisional meetings to answer questions and go over resources regarding lesser-known terms that students may be using.

An additional resource is the Incident of Bias Report, linked on the downloads section of the US Students group on RomanNet, which serves as the school’s most immediate line of defense. Yet the system isn’t without discrepancies.

According to Interim Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Kasey Taylor, while the Incident of Bias Report has uncovered circumstances of “someone overhearing a scenario that was happening” or “reporting on behalf of someone else” regarding anti-LGBTQ+ language, “even if there’s 10 or 20 [stories], [the] report system doesn’t reflect that.”

While the number of incidents might not match up, there are a variety of reasons that students may want to report incidents through other channels. “Some students for various reasons are reluctant to fill [the form] out, and so I think the best thing they can do is identify a faculty member—an adult in the community—[that] they’re close with and talk to that person,” Mr. Woods said. “And that person can help lead them either to the Incident of Bias Report or bypass that.”

Faculty are already seeing this type of reporting occur. Mx. Hansberry said, “Students, both in affinity group spaces and outside of affinity group spaces, have told faculty [about] specific instances of a specific day or time that somebody said a word to them, so there’s [very] concrete examples.”

In terms of the causes of the surge, external events have likely influenced Latin’s climate. “It does mirror what’s happening nationally with a lot of groups right now, just lack of tolerance [and] respect,” Upper School history teacher Kristin Gulinski said.

Mx. Hansberry agreed. “If we look to the world outside of Latin, LGBTQ hate has increased in public conversation,” they said. “There are major political figures and political candidates who openly dislike LGBTQ people. When public figures and politicians are saying that, it’s going to trickle into school.”

In fact, Latin is not alone in the surge they’ve been seeing. In a national study, over 70% of queer youth reported that they had heard homophobic remarks from some or most students at school, and 20% reported that they had heard homophobic remarks from faculty or staff.

The numbers are devastating, but they don’t necessarily imply ill intent. Students may not be conscious of the potential negative effects of their actions. “Some of the things people say are hateful and harmful, and then there’s also some things people say that are maybe just out of ignorance or a mistake,” Mx. Hansberry said.

In a similar vein, community members like Mx. Hansberry feel there is a more expansive issue at play when discussing the possible causes of anti-LGBTQ+ language: an implicit bias that stems from a myriad of sources.

“I think some of this is [that], unfortunately, everyone has their biases and stereotypes in their mind,” Mx. Hansberry said. “There’s no community that’s free from that.”

Feeding into this issue is a lack of media literacy. “Kids have increased access to social media, and they probably have less research skills,” Mikayla said. In fact, in a study by Cambridge University, younger audiences were shown to fall more readily for fake news, meaning Latin’s teenage demographic is particularly susceptible to misinformation.

Education is widely regarded as an important step in combating this problem. “A lot of stigma comes from misinformation, and so a step that everyone can take is making sure they stay informed,” Stephen said. “And then once they have information, sharing it and making sure their friends stay informed.”

However, community members like Mr. Woods also feel that changing the environment Latin is seeing involves deeper pedagogical shifts.

“We need more visible consequences for a whole host of things than we have now,” he said. “The most immediate thing is [that] the behavior needs to stop, and I happen to believe that immediate consequences are the best way to do that.”

Mr. Woods is not alone—many have reacted to the surge by honing in on the social changes they would like to see at Latin. “Making othering comments is not okay, and it is not entirely on queer people to tell you that it’s not okay,” Stephen said. “It is your responsibility as a community member at Latin to say, ‘No, you can’t say that,’ to say, ‘Here’s why,’ [and] if you aren’t comfortable saying that, to bring it up with an adult.”

Ms. Gulinski said, “It’s not an easy situation to be in as a student, having to challenge your peers, but at the same time, it’s disrespectful behavior, so change needs to happen.”

Aside from ensuring that they hold the community accountable, Latin’s queer communities feel that the community could benefit from being more understanding and empathetic. “Number one, respect people as people,” Mx. Hansberry said. “You do not have to understand every nuance of someone’s personality to be respectful of it.”

Similarly, Ms. Gulinski said, “Anyone can preach tolerance, anyone can be respectful, [and] anyone can be understanding and empathic to each other. We need more of that in the world right now in a lot of different capacities.”

Scarlet Gitelson (‘26) is delighted to be serving as one of this year’s Managing and Standards Editors. Using her writing, she seeks to promote connection...

Carolena Tognarelli (’26) is a sophomore at Latin who joined The Forum this year. She enjoys writing creatively, but will never pass up an opportunity...

Mr. Joyce • Feb 1, 2024 at 2:58 pm

Scarlet and Carolena, thanks for this good piece. I was not aware that these incidents appear to be on the rise, so I appreciate the reportage. That’s unfortunate. I’ll try to be more attentive.