History on Trial: Sophomores Excel in Nazi Mind Final

@latinupperschool on Instagram

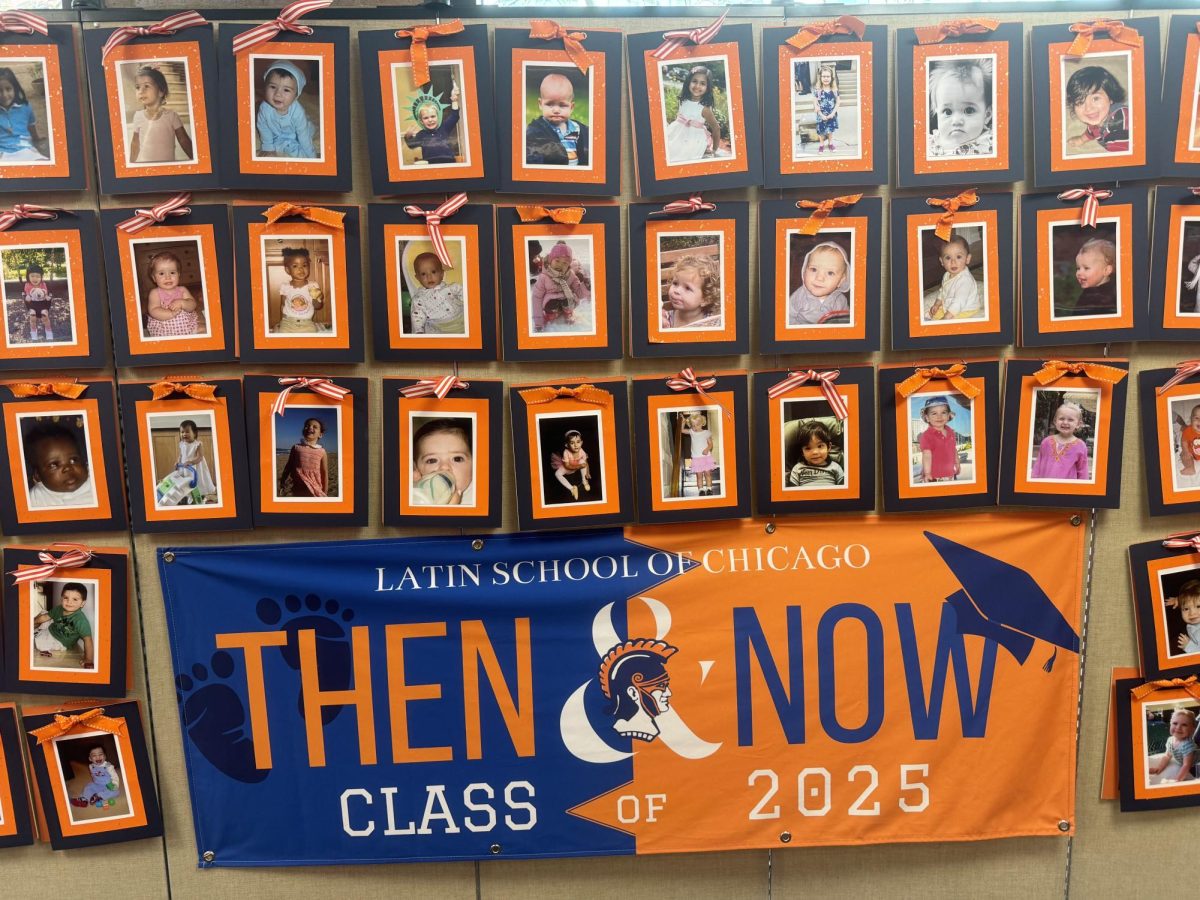

Members of this year’s Nazi Mind class pose together after a long day of hard work.

For 46 years, Nazi Mind has held its title as one of the most recognizable classes offered at Latin. Stories of the trial are passed down from parents to children, from sibling to sibling, and everywhere in between. The class final, a mock Nuremberg Trial, draws students in on its own, and this year’s trial will certainly be remembered as the culmination of the sophomore group’s hard work and as one of the most thorough, well-thought-out mock trials in recent history.

Nazi Mind was first offered in 1978 when Upper School history teacher Ingrid Dorer–Fitzpatrick arrived at Latin halfway through the school year.

“[Ms. Dorer] was supposed to teach a class called the American Family, which she didn’t have any background in or knowledge about,” Dr. Matthew June, Upper School history teacher and the current instructor for Nazi Mind, said. “But she did have a background in psychology and also an interest in history related to World War II, so based on these interests she had the idea for this class to really look at World War II and the Holocaust from a perspective that took into account both history and psychology.”

Ms. Dorer had just finished teaching at the university level in Italy about dictatorships and the psychology behind them, and she decided to apply her knowledge to the new classes she wanted to create. The result was not one, but two new classes added to the Latin curriculum, the other being yet another sophomore history elective, Russian Revolutions.

The idea of the trial itself, however, was equally unprecedented. Ms. Dorer said, “Students were so interested in trying something different, and then in year two, they turned it into something it was never designed to be. This was not my brain child; it was students’ brain child. And it’s hard not to be responsive when kids really want to do work.”

This class has now been offered for over four decades. Every year, students have the opportunity to develop unique verdicts and interact with a cycle of cases that often have not been used in recent years. “The cases are picked by what’s in the news most right now. What are some of the issues we’re particularly concerned about?” Ms. Dorer said. “What’s justifiable by military necessity? What’s excess and maltreatment of civilian populations?”

The trial began with the lead defense and lead prosecution presenting two pre-trial motions: a motion on behalf of all defense and another to prove the criminality of the Schutzstaffel, neither of which passed. After months of preparation, the main part of the trial was put into play: 11 prosecutors, 11 judges, eight defense attorneys, and six intriguing cases. The defendants this year? Joachim von Ribbentrop, Rudolf Hess, Baldur von Schirach, Hans Frank, Karl Dernitz, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, each of which prosecutors could charge with war crimes, crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, and conspiracy.

“Once I got used to being above everyone else, seat-wise, and learning what my volume had to be and stuff like that, my stress kind of went down.” Gillian Herman, one of two Chief Justices at the trial, said.

“I was trying to convict Rudolf Hess of war crimes and crimes against humanity, which did not work out,” Zoe Curry, a prosecutor in one of the six cases, said. However, she explained that the difficult task of charging the defendant on crimes he had not been convicted for in the original trial was ultimately rewarding. “I felt the most relieved when I finished my closing speech and it was all done.”

While some students could relax early on once their case was over, others who had to wait until the later hours of the trial stayed engaged with their classmates’ cases.

Kelsey Riordan, Ernst Kaltenbrunner’s defense attorney, said, “I found the cross-examination of every case very interesting, and especially how both defendants and prosecution reacted off of each other and had to adapt in the trial to really form their argument.”

“When you take it your sophomore year, you’re so into your specific part of the trial that you don’t really notice all the hard work that other kids put into it because you’re so self-centered on that day for a good reason,” Maggie Zeiger, a senior TA for Nazi Mind, said. “But this year I really got to see how the hard work of all of the kids paid off, and that was really unique.”

In the end, two out of six defendants were sentenced to death, while the other four were given various sentences ranging from five to 30 years depending on what evidence the prosecution and defense decided to provide. “[The judges] went in thinking that we were going to give a few people much harsher sentences, but after hearing rebuttal from the defense, we thought twice about that,” Gillian said.

Ava Nelson, a prosecutor in the mock Nuremberg, said, “I got home from the trial, and I literally cried because it was something that we had been working up to for so long and I just couldn’t process that it was over. I couldn’t understand because I loved it so much and then it was just completely done”

“From A-Z, every student did the work and was still doing the work and showed up at court on Sunday as prepared as they possibly could be,” Dr. June said. “This year, every single student was ready to go, and it showed.”

Lucia Meno (’26) is thrilled for her second year on The Forum and her first year as News Editor. In the past, she’s delved into the meaning of Latin...