Lincoln Park: A Dark, Hidden History

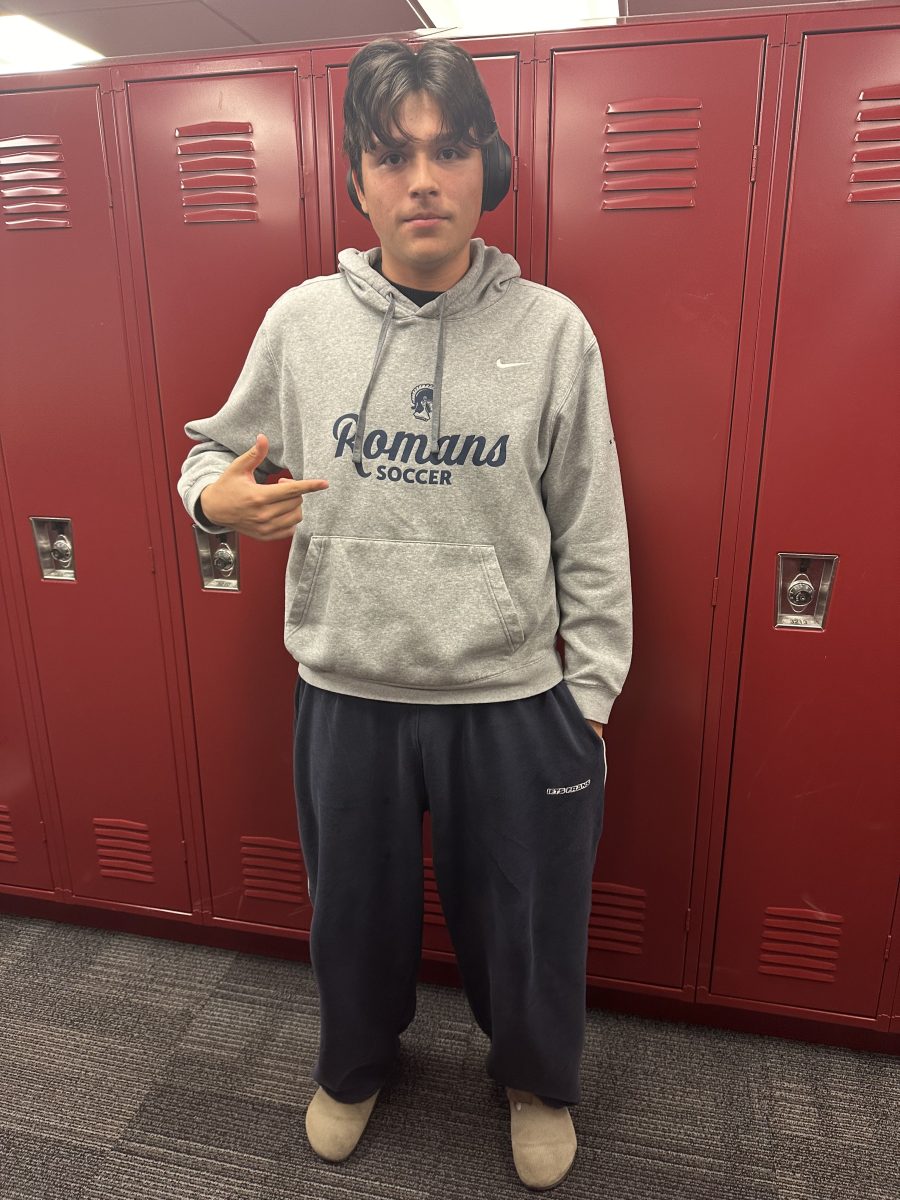

The mausoleum, a building meant to house tombstones, standing in Lincoln Park, just outside of Latin.

It’s a brisk winter afternoon, and as Latin Middle Schoolers pour out of the building, their breath becomes visible in the cold. Excitement flows through the air as their laughs roar through the city streets and into Lincoln Park. The cold wind nips at their faces as they run to a small patch of grass off LaSalle Drive. The only thing drowning out the sound of the busy street is the crunching of the snow beneath their feet and their cheers of happiness. They don’t even notice the reminder of the grim history of the ground they are standing on.

Overlooking the children is a mausoleum, something one would expect at a cemetery, not a public park. The mausoleum has the word “COUCH” on the top, a fence surrounding it. Each day, numerous students and faculty pass by the mausoleum, seldom questioning its mysterious presence.

“I used to walk through Lincoln Park all the time, [but] I didn’t know that building was a mausoleum,” Upper School math teacher Zach McArthur said. “Whoa, that’s fascinating.”

In 1858, Chicago’s first professional architect, John M. Van Osdel, was commissioned to design a mausoleum for a local family. In 1869, when families were expected to make arrangements to move gravesites out of the cemetery, the mausoleum stayed. Although it’s not clear why the mausoleum remained, by 1899 the Park District decided to let it stay permanently as a reminder of the park’s history. It has since been touched only in 1999 when it was renovated.

Along with the mausoleum, underneath the grounds of Lincoln Park there are thousands of corpses. These corpses are remnants of a grave site abandoned after the Chicago Fire. During the removal process for the bodies, there was a rush to get the bodies out, and experts believe many were left behind. Pamela Bannos, one of these experts, believes upwards of 6,000 bodies were left behind in the removal project and are still in the park.

“I couldn’t believe [the number of corpses],”senior Elsie Cohen said. “I knew there was a history of it being a graveyard, but I had no idea about the severity of the situation.”

In fact, in 1998, skeletal remains were found north of the Chicago History Museum—adjacent to Latin—when the museum was excavating for a new parking lot.

Sophomore Thomas McLaughlin, who parks in this lot, said, “[It’s] kind of disgusting, to be honest. I do not know why they did not just move them to a different cemetery.”

Naturally, some speculate that Lincoln Park is haunted because of its history, and students at Latin play into these horror stories. Freshman Sadie Cohen said, “I think there is no other explanation for a bad grade on an assessment other than the corpses being angry with us for eating lunch on top of them.”

While some students may joke about it, the reality of walking among abandoned corpses can be quite disconcerting. The mix of laughter, the vast park, and the presence of forgotten bodies creates a unique atmosphere, causing some students to reflect on history with newfound appreciation, while others simply shrug it off.

Elsie said, “I do not particularly care about the history, especially considering that much of it has to do with dead bodies underneath.”

Senior Andrew Aguirre, on the other hand, said, “[The history] makes me feel eerie because I believe in ghosts, so I feel like those bodies are improperly put there. I’m getting kind of a cold shiver over my shoulder now.”

Jim Joyce • Dec 1, 2023 at 3:11 pm

Fun piece, Gavin. I once went to a Lincoln Park Zoo event where a guest speaker spoke of alleged hauntings that she said were tied to the cemetery. This was more of a whacky Halloween-spirited thing than a scientific lecture. Anyhow, the spot with the most ghost sightings (whatever that means) was the lower level of the Lion House. So, you know, beware!

Mr. McArthur • Dec 1, 2023 at 2:05 pm

Fascinating article, Gavin. How did you first hear about this??

Laura Lewis • Nov 17, 2023 at 10:11 am

This reminds me of Cheesman Park’s history in Denver. It once was the city’s cemetery. Due to a corrupt undertaker, there are 2500+ corpses still buried underground.

Jim Harter • Nov 16, 2023 at 9:43 am

The Couch family did not move the mausoleum because too heavy/expensive. Re: remaining graves…records were destroyed during the great fire of ’71.

Delia Halko • Nov 16, 2023 at 8:21 am

Very interesting.