A New Policy: How is Latin Tackling AI This Year?

ChatGPT creates vast ramifications for education, with English and history being some of the first to see effects.

“AI should be a learning support, not a cheating mechanism,” reads the first sentence of the English and History Departments’ new AI policy, codifying Latin’s stance on the use of artificial intelligence in schoolwork. The document serves as a resource to help community members navigate constantly evolving technological tools.

One of the most well-known of these tools is the chatbot ChatGPT, which was released last November and reached 100 million users in just two months. The software uses a large language model to allow for interactive conversations and is one of many generative artificial intelligences—or those capable of creating media like text and images—that are already influencing education.

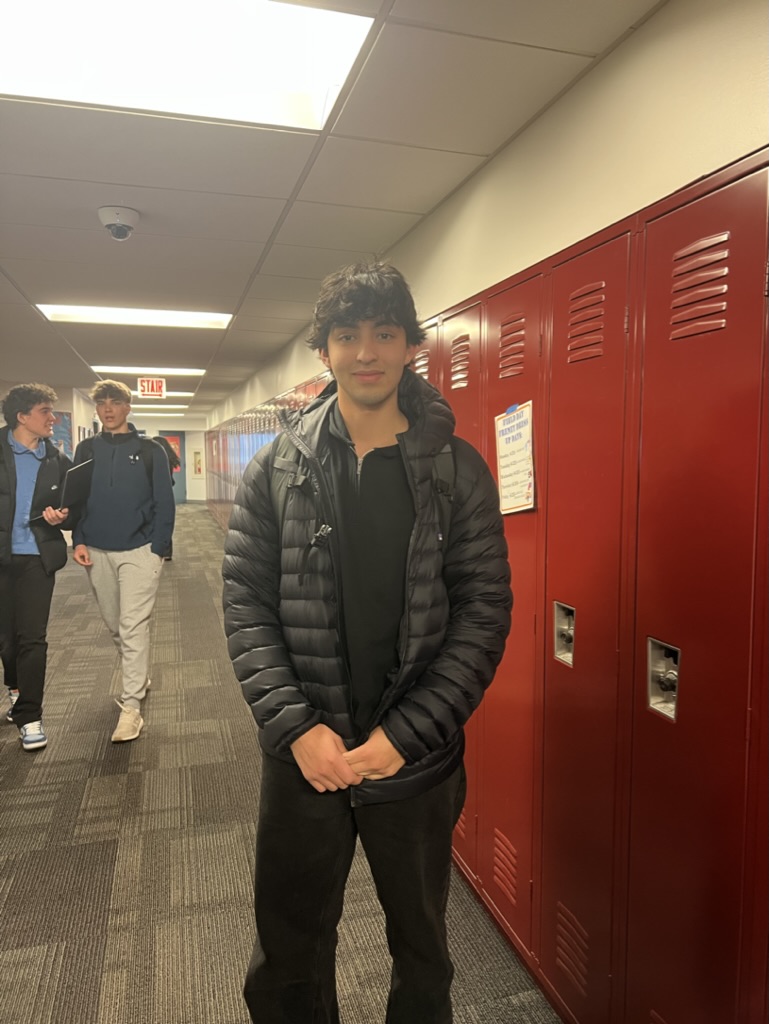

Senior Michael Cardoza said, “We have these things called Promethean moments in civilization if you relate it back to the story of Prometheus [and] when he brought fire to the humans. For humanity that was the fire, that was the wheel, that was the internet. And [now] it’s generative AI.”

As Latin heads into its second school year with these tools, the community is working to confront the fact that “AI is here and it’s going to change the way we learn and how we access information,” Upper School science teacher Faye Wells said. Innovations like the announcement on September 25 of ChatGPT’s new voice and image capabilities make these developments even more daunting, and make the new policy even more apt.

When drafting this document, US history teacher Matt June said a main goal was to “clarify what was and what was not appropriate uses of AI, and get [students] focused on understanding that any AI-generated text that is not their own idea should be treated like any other external source and be properly cited.”

As they cemented these ideas, faculty needed to come up with answers to a slew of important questions. US English teacher Kate Lorber-Crittenden asked, “How could [AI] be a tool for students, and in what scenarios is it actually inhibiting student learning?”

In the end, they came up with an analogy that fuels the policy’s sentiments. Dr. June said, “We think of it as working with a friend—you can ask each other questions, study together, review ideas, but ultimately every student knows that it would not be acceptable for their friend to write an essay that they passed off as their own.”

One of the main benefits of Latin’s policy, especially given the large amount of new terrain to explore with tools like ChatGPT, is that it doesn’t restrict teachers to any one approach. Ms. LC said, “I think it still leaves room for individual teachers to make specific choices about how AI looks in each of their classes.”

In the Computer Science Department, for example, faculty such as Computer Science Department Head Ash Hansberry try to identify possible educational uses of AI by seeking answers to some relevant questions. “What kinds of things can ChatGPT write?” Mx. Hansberry said. “And what approach does it use?”

“I’ve heard of people doing examples where they have ChatGPT write a response to a prompt and then students evaluate ChatGPT’s response and say ‘Is it accurate or not?’ or ‘Does it have the evidence or not?’ or ‘Correct its assumptions’ or ‘Provide evidence for its points,’” Mx. Hansberry said.

Exercises like these are beneficial because they help students override their initial perceptions of AI-generated text and learn to be responsible and vigilant AI users. “At first glance, an essay response from ChatGPT looks pretty great,” Ms. LC said, “but when you start digging in, one of the things that you can recognize pretty quickly is that an essay can sound really good without saying a lot.”

In addition to challenging students’ perceptions of AI, there are also teaching techniques designed to help students use artificial intelligence more productively. Important focus areas include pushing students to understand “how [to] prompt AI tools to give you the stuff that you want,” Mx. Hansberry said.

Similarly, Michael said, “What do you do in 1st grade and JK? You learn how to write. What do you do in fifth grade? You learn how to type. The next thing that’s going to come is ‘Hey, how do I write the best prompts for ChatGPT?’”

This type of guidance would allow students to interact with generative AI in ways that embrace its pros while simultaneously alleviating its cons, such as its tendency to make up references. By learning to effectively prompt ChatGPT, students could develop the skills to add evidence and citations to AI-generated writing.

Many students see this approach as potentially beneficial. Senior Ethan Weiss said, “I don’t see any issue in letting AI do some of the heavier technical lifting if it means students are still working to their own unique intellectual capacity.”

However, though these modes of instruction may have the potential to exist at Latin in the future, faculty feelings toward AI are still evolving. “I think this year, a lot of folks in the department will be trying to figure out what ChatGPT and other AI resources can do in an English or humanities setting,” Ms. LC said. “I don’t actually think enough time has passed for us to be able to say, ‘This is how Latin’s using it.’”

While specific implementation protocols have not been worked out, general sentiments among faculty, Dr. June said, are “very similar to how the Math Department approaches you all using calculators. There are definitely times we want you thinking on your own, but there are also times when it can be a helpful tool to assist the thinking.”

Michael offered a similar comparison of ChatGPT to calculators: “Do we give our first and second graders calculators? No, we don’t. Do we have our first and second graders learn how to do an outline on their own? Yeah, we do. But we give ninth graders calculators, [and] we give tenth graders calculators, because we know they know how to do the math. It’s just about making the process faster.”

Indeed, the dilemma inherent in using tools such as ChatGPT isn’t all that different from student calculator use. Mx. Hansberry explained, “Yes, ChatGPT can write a lot of simple problems for you, but if you don’t know the simple stuff yourself, then you don’t know how to catch its errors and you don’t know how to evaluate if it’s correct.”

Given the nuance of ChatGPT’s tradeoffs within education, many consider communication and collaboration to be an essential part of these discussions. “I think we would all benefit from keeping this dialogue open and revisiting this topic regularly,” Mx. Hansberry said, “We don’t know all the right answers—yet.”

Scarlet Gitelson (‘26) is delighted to be serving as one of this year’s Managing and Standards Editors. Using her writing, she seeks to promote connection...

Rohin Shah (’27) is a sophomore at Latin and is delighted to serve as news editor for The Forum. He hopes to become a proactive and investigative journalist,...