To All the (Banned) Books I’ve Loved Before

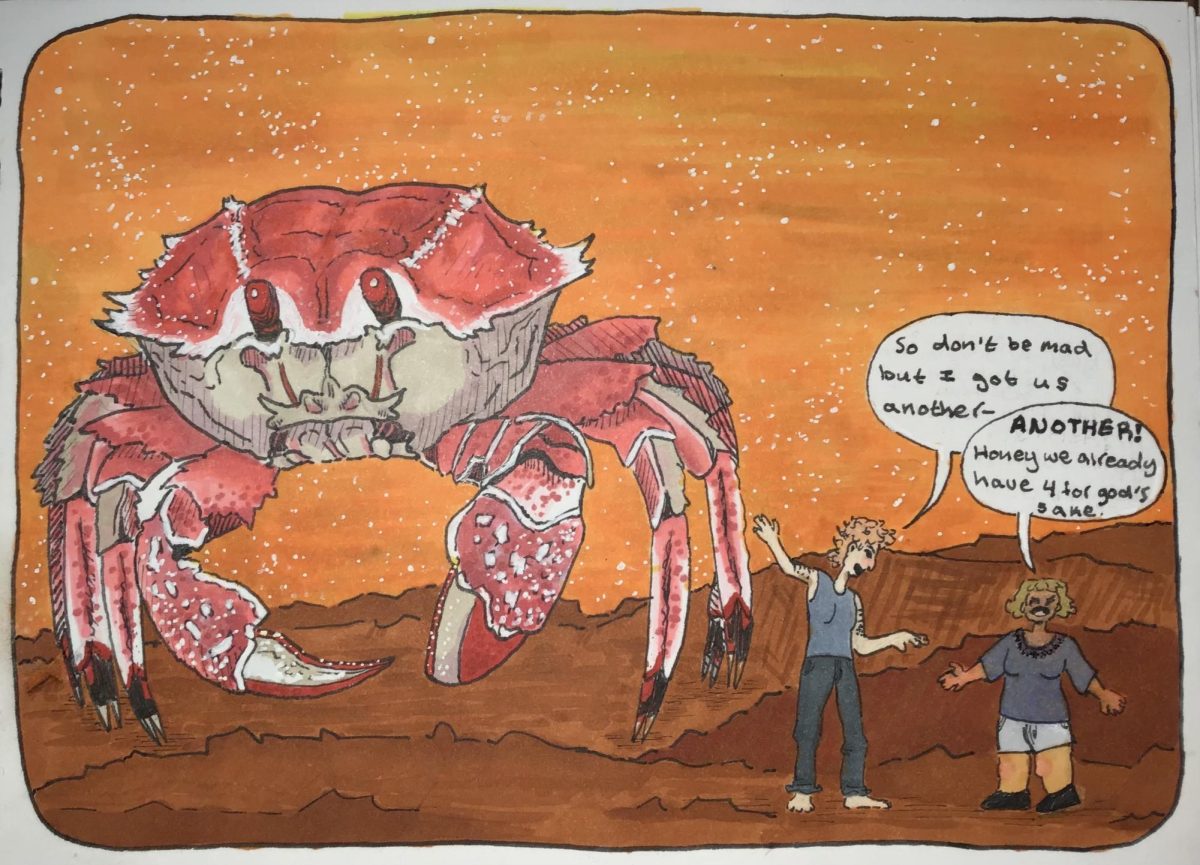

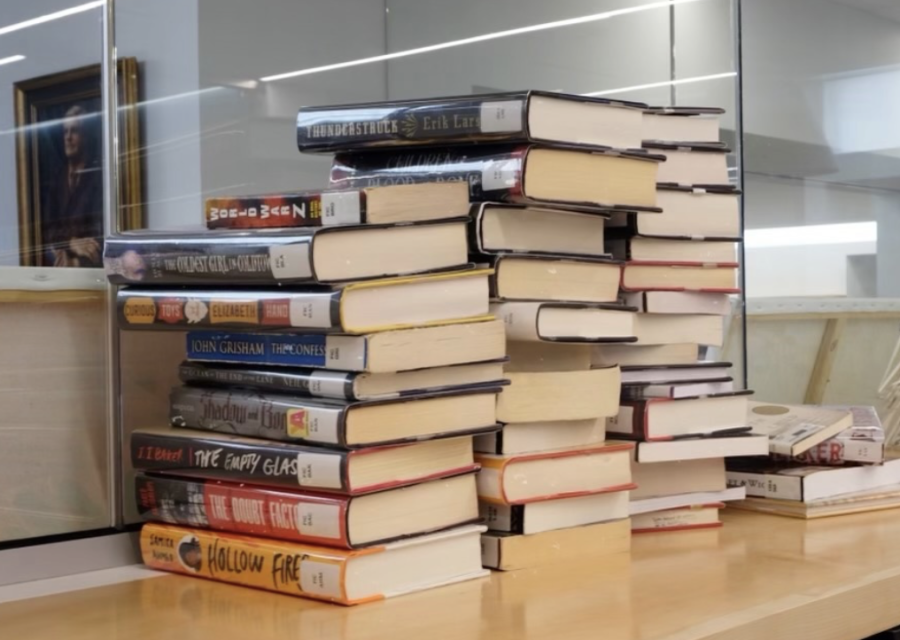

A stack of books in the Upper School Learning Commons awaiting sorting.

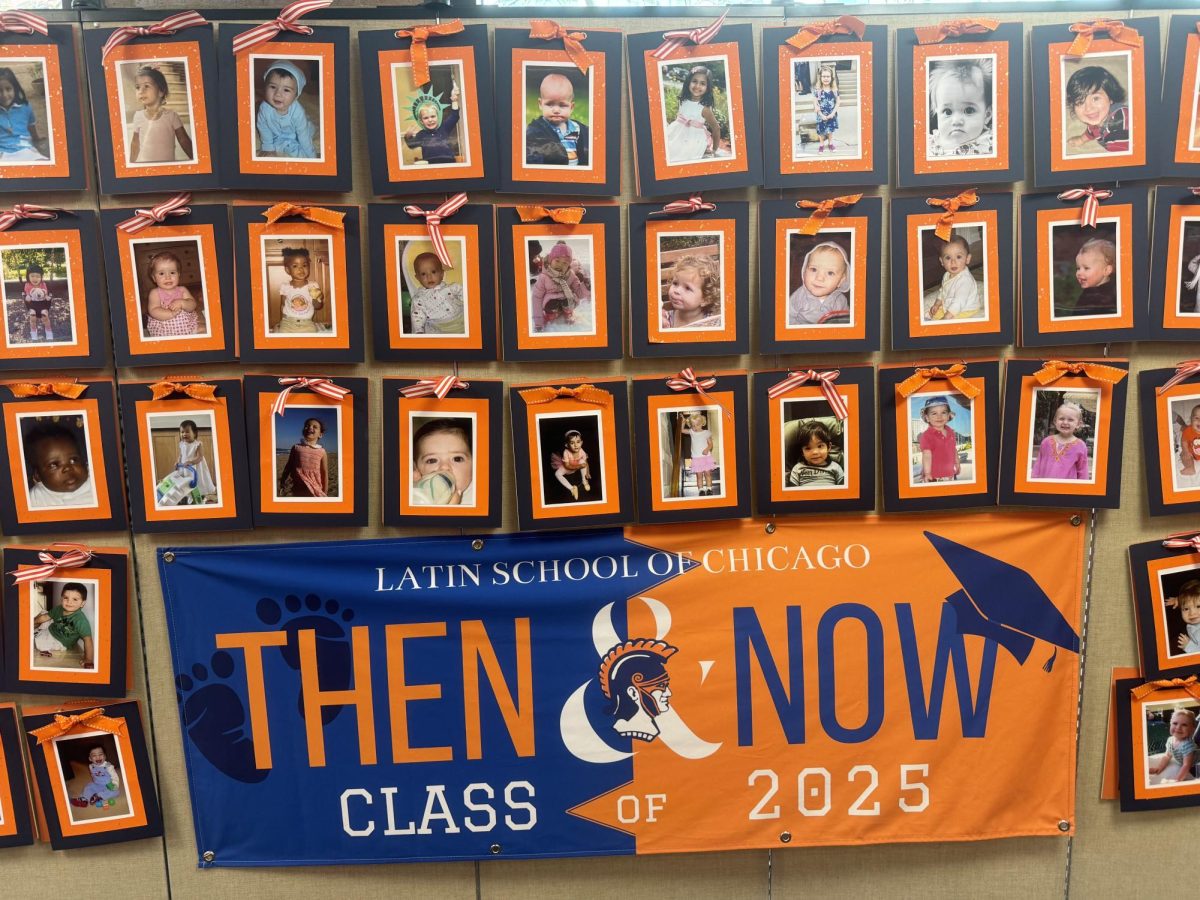

For a few weeks in September, Art Spiegelman’s comic “Maus” surfaced atop the shelves of the Upper School Learning Commons (LC) among several other books banned from schools across the nation.

Upper School librarians highlighted Spiegelman’s illustrated retelling of the Holocaust alongside titles such as “1984” and “The Hate U Give” in a display acknowledging the recent insurgence of censorship across schools and libraries throughout the country.

From July 2021 to June 2022, PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans documented the restriction of 2,532 individual titles across 32 states. Across these 123 school districts, the glaring pattern that emerged was the disproportionate targeting of books with LGBTQ+ and Person of Color (POC) narratives.

Latin’s library features more commonly banned books than just the handful in the exhibit. The “most challenged book of 2021,” “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” is found in the LC’s modest graphic novel section on the wall against the Maker Space. The unique nostalgia of tween comedy is inseparable from the thought of embarrassment: crushes, periods, and the slasher film known as puberty. Maia Kobabe, author of the infamous “Gender Queer,” lives to tell the tale. Kobabe’s autobiographical retelling of insecurity-laden adolescence and self-realized young adulthood has ignited controversy since its publication in 2019.

The degree of negative static toward the memoir from parents (though notably, not students themselves) for its depictions of a non-heteronormative childhood brought into account the long history of queer books that came before—and the place they fought for in school libraries—long prior to Kobabe’s debut.

From Madeline Miller’s acclaimed “The Song of Achilles” to the gay-best-friend limbo “Mean Girls” never quite escapes, it is not uncommon for positive depictions to have heartache for a face. Following Netflix’s cancellation of shows with breakthrough representation, the recent loss of queer media in libraries has sparked dialogue on the significance of diverse expression.

Junior Stephen Legendre, co-head of Latin’s LGBTQ affinity, wrote in an email that diverse characters “enable queer people around the world to see and interact with examples of how they can fit into everyday life.”

Normalization, a recent buzzword, is the concept of redefining a set standard and is essential to developing tolerant environments. Without dismantling these norms, Stephen continued, “it makes any queer person, especially younger queer people, question how they can have a future in a world that puts a big red mark on them that says, ‘You aren’t normal.’”

Similarly to queer spotlighting in titles, PEN’s report noted that books with narratives featuring either a POC protagonist or secondary character accounted for 41 percent of recent censorship initiatives.

Propagated by its controversy, the diasporic lull of Chinese-American author Amy Chua’s “Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother” is a collection of parental memoirs following the disputed upbringing of her two daughters. Perhaps she isn’t the mother your mother would approve of, with the intensive after-school agendas and home regimens. The book’s critical reception in 2011 placed Chua in the headlights of a widely covered media storm on the accounts of the “un-American” parenting in the memoir.

For freshman Sebastian Lee-Yee, Chua’s stories of such parenthood were read aloud to him as quaint bedtime stories. Sebastian remarked that the Asian-centric narrative of Chua’s memoir, whether exaggerated or not, had overblown the negative response. “It’s hard to unlearn 300 years of how people grew up just in a single novel,” Sebastian said. “But it’s important for Chinese-American kids not to feel like their childhoods were something to be ashamed of.”

On the receiving end of this counter-movement was, unsurprisingly, librarians. New Upper School librarian Lisa Patton has multiple lived experiences in addressing alternate solutions to banning or restricting books by content. In one of her first librarian jobs in Guatemala, a plan was needed for amending students’ hesitancy in checking out “embarrassing” books at the counter. The solution: a hand-painted bookshelf supplied with “embarrassing” books that would be entirely self-serviced to avoid the arduously awkward barcode scanning. “This shelf was just the ‘help yourself,’” Ms. Patton said.

Because this new plan would require the removal of books from the library’s cataloging system, this Guatemalan school administration raised the inevitable question: What about all of the untraceable books? Ms. Patton didn’t view this loss as the setback it appeared to be. “Then [the student] keeps the book that was important to them, that helped them through something.” By the end of the year, Ms. Patton continued, “I didn’t lose one single book.”

In a similar spirit, in just her first few weeks at Latin, Ms. Patton highlighted what are often known as banned books, rather than hiding them from Latin’s students. “Now, I’m putting those books out here, and I’m able to put a label on the importance of these books,” Ms. Patton said.

Lyla Granich (‘26) is honored to serve as one of the Editors-in-Chief this year. Through The Forum, she hopes to present a picture of Latin that is comprehensive,...