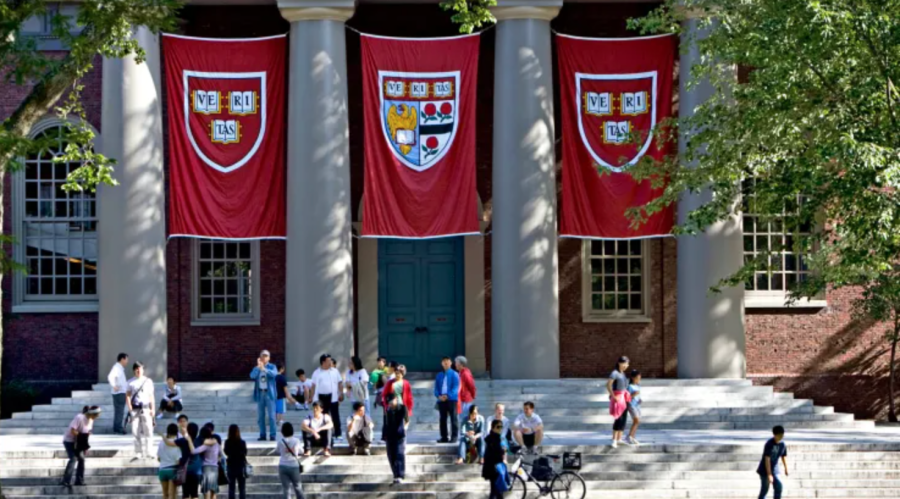

Affirmative Action in Jeopardy: Supreme Court Hears Harvard and UNC College Admissions Case

Harvard University

The Supreme Court has decided to hear a case challenging the race-conscious admissions policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, and due to the Court’s conservative super majority, the future of affirmative action may be on the line. The case will be heard next term, which starts in October, with a decision expected in the spring or summer of 2023. If the Court decides to side with the plaintiffs, a group called Students for Fair Admissions, it could dramatically change the way universities have approached admissions for the past 50 years, influencing high school students going through the college admissions process.

As juniors have been learning in their College Counseling classes, affirmative action is a process that organizations use to create diverse environments by taking different traits like race, sex, gender, religion, or socioeconomic status into account when deciding whether to admit or hire an applicant. This process started in the 1960s with the civil rights movement, which shed light on racial segregation and discrimination in the U.S. This racial division extended to college campuses, leading college admissions departments to adopt affirmative action policies in an effort to integrate their student bodies and increase access to higher education. Latin college counselor Devon Jones said, “The goal of affirmative action is to create access to opportunities for a wide range of people who have historically been excluded and to help ensure the population of the organization is an accurate reflection of the larger demographic.”

The current Supreme Court case is a pairing of two affirmative action cases filed against Harvard and UNC. The Harvard case was filed on behalf of Asian American students who claimed that they were unfairly discriminated against in Harvard’s admission’s process. Forbes writer and college professor Evan Gerstmann wrote an article describing the students’ complaint, saying, “The reason that it is harder for Asian Americans to get into Harvard is that their ‘personal ratings’ (a subjective evaluation of personal qualities) are, on average, significantly lower than for white applicants.”

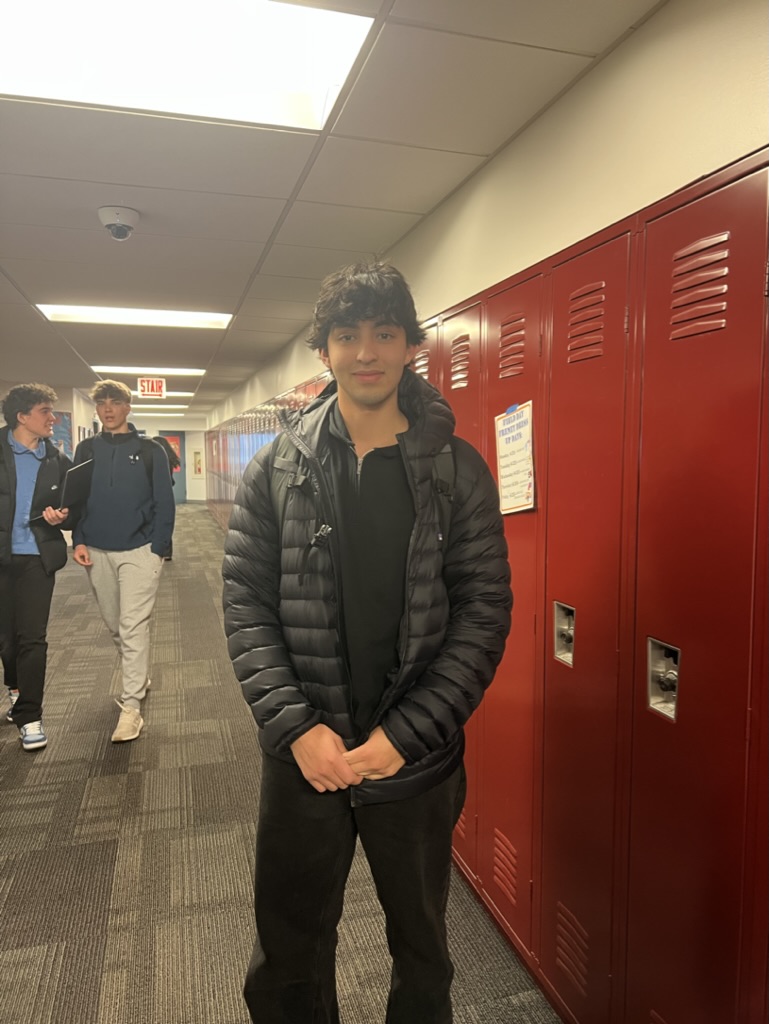

Senior Andrew Young, co-head of the Asian Student Alliance (ASA), cited the “model minority myth” as the reason why some people think Asian American applicants are held to a different standard. Andrew said, “The problem with the model minority myth is that it often feels like [Asian American students’] accomplishments are to be expected of us, which ignores the hard work and sacrifices that go into them. And if we fail to meet these expectations, then it kind of feels like no one cares about us because we’re not fitting into the stereotypes created by the model minority myth.” In regards to whether affirmative action accounts for these biases, Andrew said, “Generally speaking, I find affirmative action to be a bit of a touchy subject when it comes to the Asian American community. On one hand, we want to support colleges’ commitments to diversity and equity, especially considering our own past of being discriminated against. On the other hand, a lot of us worry that affirmative action feeds into the model minority myth—the idea that Asians are naturally gifted or smart.”

Junior Sanaiya Luthar, another co-head of ASA, noted, “Another stereotype that the model minority myth often perpetuates is the uni-dimensionality of Asian American interests: Put your head down, get your homework done, study hard.” She added, “I also wonder, though, if the myth harbors any influence over Harvard interviewers’ statistically unfavorable evaluations of the diverse Asian American personalities in their application pool.”

The UNC case was filed on behalf of both white and Asian American students, claiming discrimination because UNC favored Black, Hispanic, and Native American applicants. Sanaiya said, “Students who have an identity that affirmative action policies generally target probably worry about the reductionist lens their peers could view them through. ‘Oh, you only got in because of X identity’ is common rhetoric used to demean and discriminate against underprivileged, well-qualified students.”

Students for Fair Admissions explained their position in a brief asking the Supreme Court to hear their appeal, writing, “If a university wants to admit students with certain experiences (say, overcoming discrimination), then it can evaluate whether individual applicants have that experience.” The brief continued, “It cannot simply use race as a proxy for certain experiences or views.” Both of the cases were unsuccessful in the lower courts, so the Supreme Court’s decision to pair them as a singular case, which is rare, signals that the Court may be planning to issue a landmark decision that overrules past precedents.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld challenges to affirmative action. The most recent Supreme Court case addressing affirmative action was issued in 2016, when Abigail Fisher, a white student, was denied admissions to the University of Texas. She sued the school, claiming that it violated her constitutional rights under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause by considering race in the admissions process. The Supreme Court sided with UT, concluding that the consideration of race as a factor in its holistic review process was constitutional because it was necessary to obtain the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body.

Despite affirmative action being historically supported by the Supreme Court, the current Harvard/UNC case could erase that standard, which would be a major step backwards for affirmative action supporters. Deborah Linder, Upper School history and politics teacher, is concerned that the Supreme Court may be poised to overturn the longstanding precedent of upholding affirmative action in college admissions. “As a historian, I have to look at history in a big picture way,” she said. “So every time that these little steps backwards happen, and things go up and things go down, I hope, as Dr. Martin Luther King said, ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.’”

When asked how a potential Supreme Court decision ending affirmative action could impact the college admissions process, Ms. Jones said, “It’s possible that the admissions process could become less equitable, creating more homogeneous incoming classes year after year.” She added, “While we’re now at a place where people from all backgrounds are allowed to access all levels of education, we have not yet arrived at the moment in history where the vast majority of college campuses are truly reflective of the diversity represented around the country. The ultimate goal is for there to be no need for affirmative action, but until we reach that point, these policies need to be enacted in thoughtful and unbiased ways.”

Andrew said, “Many minorities still feel underrepresented in colleges, so perhaps the current form of affirmative action isn’t working.”

Sanaiya cited another problem with the current structure of affirmative action, saying, “We’re applying affirmative action policies far too late in the game, which explains why colleges aren’t diverse enough.” She continued, “Informal segregation is embarrassingly abundant in the American primary and secondary education systems. It makes sense that racial and socioeconomic homogeny (not diversity) are also the norms in college. How come we only start applying the principles of affirmative action at large when at a collegiate level?”

With all of the discourse around affirmative action, college admissions offices are faced with a quandary of how to ensure diversity without getting accused of discriminating against certain students. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas supports a “colorblind” approach. In a prior Supreme Court case challenging the University of Michigan Law School’s admissions policy, Justice Thomas, in a separate opinion that concurred and dissented, in part, with the majority opinion of the Court, cited abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ famous speech, “What the Black Man Wants,” when Douglass says, “Do nothing with us [Black people]!” Justice Thomas said, “Like Douglass, I believe Blacks can achieve in every avenue of American life without the meddling of university administrators.” Further, Justice Thomas stated, “[A] University may not maintain a high admissions standard and grant exemptions to favored races. The Law School, of its own choosing and for its own purposes, maintains an exclusionary admissions system that it knows produces racially disproportionate results. Racial discrimination is not a permissable solution to the self-inflicted wounds of this elitist admissions policy.”

However, many argue that being “colorblind” allows for people to ignore potential racial biases and discriminatory views. Adia Harvey Wingfield, a writer for The Atlantic and a professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis, wrote, “Many Americans purport not to see color. However, their colorblindness comes at a cost.” She continued, “By claiming that they do not see race, they also can avert their eyes from the ways in which well-meaning people engage in practices that reproduce neighborhood and school segregation, rely on ‘soft skills’ in ways that disadvantage racial minorities in the job market, and hoard opportunities in ways that reserve access to better jobs for white peers.”

Ms. Jones added, “Adopting colorblind admissions policies is not the answer, in my opinion.” She said, “To practice holistic admission means to consider an applicant in their entirety. While there is no race or ethnic group that is a monolith, for many, understanding that part of their identity is supremely important and is an essential factor in understanding them in their totality.” She added, “To be blind to what is often a very important identity to someone is to not fully see them at all.”

Andrew also said, “Maybe we’re actually considering the wrong questions, though—instead of wondering if affirmative action is simply good or bad, maybe what we should be thinking about is how we can improve affirmative action.” He added, “What we need to do is figure out how colleges can make the college process clearer to applicants while also truly making colleges more inclusive—the latter of which is what I believe should be the heart of affirmative action.”

When the Supreme Court issues its decision in the Harvard/UNC case, it will directly impact Latin students who are going through, or will be going through, the college admissions process. With a conservative-leaning Court that appears willing to overrule long-standing precedents in high-stakes cases, the case could fundamentally transfer the college admissions process and affect the diversity of student bodies on college campuses across the country.

McLaine Leik (‘23) is thrilled to serve as The Forum’s Managing and Standards Editor this year! She has been writing for The Forum since her freshman...