Latin Students Assess Standards-Based Assessment

Responses from Student Survey

It seems like the acronym “SBA” is popping up everywhere. Appearing on Quarter 1 grade reports this year for the first time ever and a frequent agenda item for student and parent meetings with the administration, SBA (Standards-Based Assessment) plays a major part in every Latin student’s academics. The Forum sent out a survey to all Upper School sophomores, juniors, and seniors (the survey was not sent to freshmen, as they have not yet received letter grades in SBA classes) to gather more information on students’ views about SBA, and in particular, Latin’s approach to converting SBA to letter grades on grade reports.

SBA uses different standards to assess a student’s level of proficiency with regard to certain skills and learning objectives. It allows students to progress at their own pace and to do multiple retakes of assessments and rewrites of essays. Upper School Director Kristine Von Ogden created a presentation outlining the goals and current approach to implementing SBA across departments at Latin. In the presentation, she said that Latin is still in the “developmental, roll-out stage” of SBA, “working through many iterations,” with the ultimate goal of an “aligned approach within and across disciplines with common vocabulary and a common approach to grade conversions.”

Ms. Von Ogden noted that one of the principal goals of SBA is more equitable grading, and indicated that questions had been raised in the Latin community about Mastery Transcript, an alternative transcript model that eliminates letter grades and, instead, displays a student’s ability to demonstrate certain skills and competencies, similar to those found in Latin’s SBA rubrics. But she emphasized that, here at Latin, “letter grades are not going away, certainly not in the short term.” In the meantime, Latin uses different SBA models in different classes, which then, at the end of the first semester and again at the end of the year, convert to traditional letter grades.

The Science Department uses a four-level scale for feedback: 5, 6, 8, and 10, with 5s representing little to no understanding of a standard, and 10s representing full understanding. In an interview with The Forum, Geraldine Schmadeke, the Chair of the Science Department, said, “These levels of feedback could be called anything. For example, they could be simply different colors to denote progress towards mastery—red, orange, yellow, green.” Different science classes convert the 5-6-8-10 scores to final letter grades differently, and all classes allow for retakes.

Chair of the Language Department Xavier Espejo-Vadillo described the department’s assessment system, saying, “Latin, our classical language, uses a rubric based on reading comprehension that has seven standards. French, Mandarin, and Spanish are our three modern languages, and all use the same rubrics, which are based on proficiency levels, to help us gather and assess evidence of language learning and help us determine students’ proficiency levels.” For Latin, the descriptors of proficiency levels are labeled low, mid, high, and superior, and for the modern languages, the descriptors are labeled exploring, engaging, and established. When converting the descriptors to letter grades, teachers use a rubric and methodology described here for Latin classes and here for modern language classes.

The History Department assesses 9th through 11th grade classes with a four-point scale, with 1 being the lowest level and 4 being the highest, and is currently developing an SBA rubric for 12th grade. Ernesto Cruz, Co-Chair of the History Department, said, “Simplicity really is what the History Department was looking for. That’s why we convert grades the way we do, with a mode of 4=A, 3=B, et cetera. We have a whole list of rules for tiebreakers that are in the students’ favor, resulting in B+’s or A-’s.” A chart describing the rubric used by the History Department is attached here.

The English Department uses a similar method as the History Department, assessing students on a four-level scale, converting to a letter grade using the mode. Kate Lorber-Crittenden, Interim Chair of the English Department, said, “We do not use A-B-C-D, because the whole idea is to get from an arbitrary description of a `B’ or an `A’ and instead communicate more clearly what a student can do.” She continued, “A true SBA approach would actually not end in a grade conversion, but we aren’t there yet. So for now, we do have this forced step to convert to a grade.”

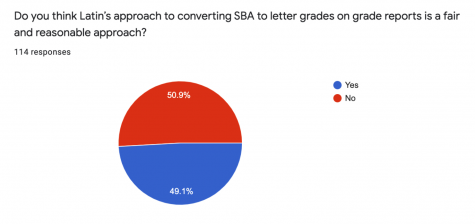

The first question in the Forum’s survey of 10th-12th grade students asked, “Do you think Latin’s approach to converting SBA to letter grades on grade reports is a fair and reasonable approach?” The survey was sent to 384 students and received 114 responses, and of those responses, 50.9% said no and 49.1% said yes. Elaborating on this survey question in a follow-up interview, junior Elizabeth Box said, “I believe that the SBA system does have its strengths, but when converting to letter grades, I feel it does not fairly represent a student’s greatest strengths.” Elizabeth also expressed concerns about the majority of assessments being solely based on writing, instead of assessing on class participation as well.

Additionally, junior Alice Mihas feels as though some SBA classes, specifically language courses, assess on where the student should be at the end of the year instead of the end of the semester. She said, “This inherently causes students’ grades to suffer in the first semester, which shouldn’t really matter, but for seniors applying to colleges, this can be quite the deficit for their application due to them having to submit their first semester grades.”

In response, Mr. Espejo-Vadillo said, “Alice’s is a concern that I have heard, and I believe it is confusing for students. We can do a better job, perhaps, educating the community about SBA in languages and across the school.” He explained, “We are not assessing what students should know by the end of the ‘year’ but assessing students’ journey to the next proficiency level. That is, there is a set of content and practice broken down in quarters and/or units that offer practice at the level students are currently at, and expand to the next proficiency level.” In regards to first semester grades, he said, “When we assess Quarter 2, we are not including content we have not covered or a skill that has not been fully introduced. However, some students might already show they are grasping it and may start using it in their work.”

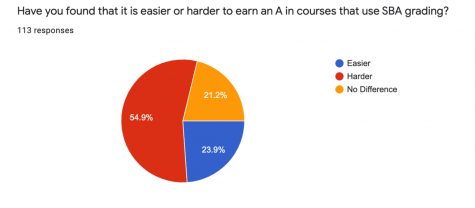

The second survey question asked, “Have you found that it is easier or harder to earn an A in courses that use SBA grading?” Out of 113 responses (the only survey question with 113 responses instead of 114), 54.9% said harder, 23.9% said easier, and 21.2% said no difference. Junior Patrick Shrake said, “I think that in classes that have fewer assessments, it is much harder to get an A than in classes that have more assessments.” He suggested that more SBA classes should assess more often so students can focus on learning instead of stressing about singular tests.

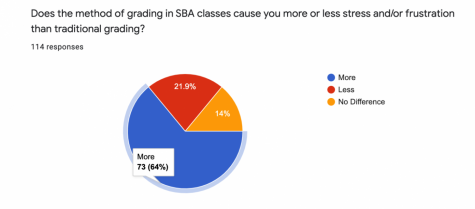

The survey then asked, “Does the method of grading in SBA classes cause you more or less stress and/or frustration than traditional grading?” On this issue, there was greater consensus, with 64% saying more, 21.9% saying less, and 14% saying no difference. With respect to science classes, junior Sofia Uddin said, “SBA is more stressful because if you make one mistake then you automatically earn an 80%.” Elizabeth commented on the never-ending nature of reassessments, saying, “I think it definitely makes me more stressed because, although the reassessment process is helpful, when wanting to reassess multiple times, your free blocks, before school and after school can get very busy.” On the other hand, Patrick said, “I think that it really depends on the class. Some classes add stress, while some definitely create less.”

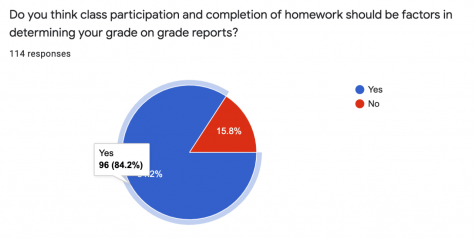

The next survey question was, “Do you think class participation and completion of homework should be factors in determining your grade on grade reports?” An overwhelming 84.2% of respondents said yes, and 15.8% said no. Following a recent Student Academic Board (SAB) meeting with Ms. Von Ogden at which students vocalized many concerns about SBA, senior and a head of SAB Vivie Koo noted that students felt that they “need a space for participation and engagement to be worked into [the] grading scale—there is no motivation to do anything that isn’t worked into your final grade.”

Ms. Lorber-Crittenden offered a response as to why SBA does not factor homework and class participation into grades, saying, “Homework and participation are tools that are intended to help students practice and learn the skills, but including these things in a grade doesn’t mean you’re actually assessing the skill. Consider a few of the various factors that contribute to whether a student completes their homework and how: Do they have a quiet place to work, do they have other responsibilities at home or after the school day that cut into their time to complete their work?” She summarized, “If homework makes up a percentage of a student’s grade, then their grade now includes factors beyond their control—factors that are certainly not related to their ability to learn English skills.” Ms. Lorber-Crittenden also said that including class participation in a grade unfairly favors extroverted students, while penalizing quiet students who understand the material just as much.

The department chairs explained their rationales for why they think SBA works for their respective departments. Ms. Schmadeke said, “We think four levels of feedback is sufficient. It gives students a good idea of where they stand on each Learning Objective and how far off they are from showing full mastery.” Ms. Schmadeke, asked why the 5-6-8-10 grading scale in Science does not include 7s and 9s, even though these scores are ultimately converted to letter grades based on a 70-80-90-percent scale, which was a criticism raised at the recent SAB meeting, said, “The question about the lack of a 9 is a not uncommon question. We have found that, almost without exception, the question stems from having a traditional mindset with respect to assessments and grading.” She continued, “By the end of the year, when students have more fully internalized our SBA system and have seen how it plays out in practice, any concern about a ‘lack of a 9’ tends to have faded away.”

When asked why the sciences did not include a letter grade on first quarter grade reports, Ms. Schmadeke said, “Using SBA, students have multiple opportunities to demonstrate mastery of the learning objectives. These skills will develop over time, and we do not expect our students to have fully mastered them in the first quarter of the school year.”

Despite the varying opinions about the effectiveness of SBA in the Language Department, when asked why he thinks SBA works the best for languages, Mr. Espejo-Vadillo said, “SBA measures what you can do in the language, i.e, your proficiency. Proficiency is defined as sustained performance at a level and transitioning to the next one.” Mr. Espejo-Vadillo explained, “SBA offers students a great picture of where they are at in their language learning journey in an objective way. You could think about sports as a way to compare. Succeeding in a sport calls for sustained performance, and successful practices are shared in sports and language learning: practice (repetition), memory, muscle memory, observation (modeling), being coached (feedback), more practice (with others), monitoring progress (reviewing feedback and goals), strategizing, even more practice and rest.”

In regards to the History Department’s approach to SBA, Mr. Cruz said, “We adopted modal grading because it was, in our estimation, the most equitable way to calculate grades based on what we are doing. With mode, students are given maximum credit for the skills they are excelling at, while minimizing the penalties for not being able to do something, yet.” He continued, “It also gives students the ability to, in essence, drop their own lowest scores by continually improving their performance over time.” When asked why history uses a 1-4 scale instead of letter grades, he said, “There are a lot of reasons we use the numbers rather than the letters. The big one is that we are trying to move away from using letters entirely. The letter-based grading system has its origins in the eugenics movements of the early 20th century. The same thinkers that brought us Jim Crow and the Nuremberg Laws created the letter grade system. As teachers of history, we’re attempting to learn from the past, and grow beyond our culture’s mistakes.”

When asked to respond to the concern that SBA makes it more difficult to earn an A, Mr. Cruz said, “Under the standard letter grade system that students seem to love so much, A’s should be earned by only a handful of students, with the average being a C. It’s as if everyone wants to be told they’re special, not realizing that under that kind of system no one would be special.” He continued, “This really gets at the issue at the heart of this whole thing: learning. Grades aren’t learning because grades have been so inflated for so long, that any attempt to accurately document the amount of learning that’s going on is going to seem painful and unjust. The real injustice is how inflated things have gotten.” In regards to the connection between grades and learning, Mr. Cruz said, “I owe you more than a grade; I owe you an education. And this current teapot tempest about SBA tells me that for many in this community, grades matter more than education, and that these two concepts are no longer aligned in any meaningful way.”

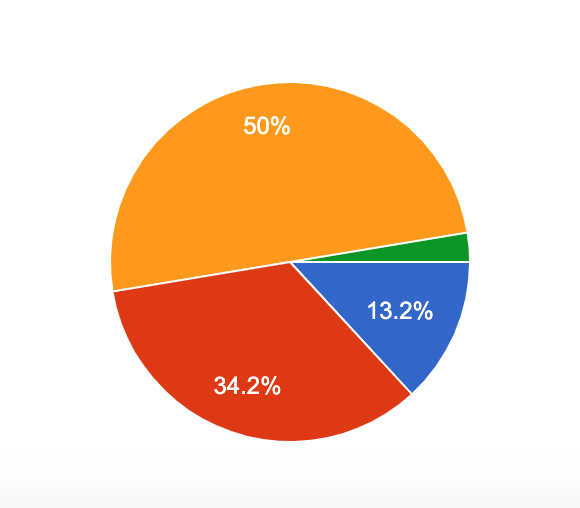

The final question on the survey asked students to grade Latin’s overall implementation of SBA, using the Science Department’s 5-6-8-10 grading scale: 2.6% of students gave it a 10; 50% gave it an 8; 34.2% gave it a 6, and 13.2% gave it a 5. There are multiple ways that SBA classes convert scores to letter grades, including either taking the average of all of the scores or simply taking the mode of all the scores as the final grade. So, if one converts these scores to a letter grade by taking the average of the 114 responses, the result is a 69.7%, which, rounded up, is a C-. If one calculates the letter grade by taking the mode, the result is a B-.

As the faculty and administration continue to work to improve Latin’s SBA model, they may want to take into account the results of this student survey. As junior Ellie Baker said, “SBA is such an integral part of my high school academic experience, yet I feel like SBA is a flawed system. And though SBA itself allows me to retake, I can’t retake my high school academic experience.”

McLaine Leik (‘23) is thrilled to serve as The Forum’s Managing and Standards Editor this year! She has been writing for The Forum since her freshman...