In-Class Essays Increase Stress Among Students

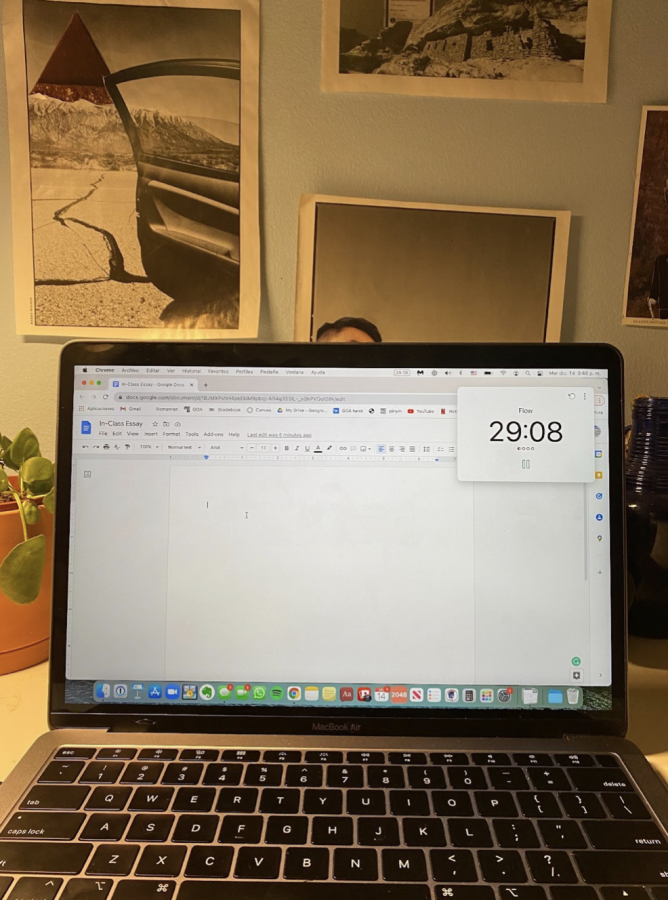

In-class essays are a core part of the English and history curriculums at Latin, and, at one point or another, we have all speed written our way through a class period, holding our breath while our fingers aggressively hit the keys.

Apart from observing performance under pressure, in-class essays are not the best way to assess students. When it comes to a fact-based focus, like history, timed essays don’t adequately show how much a student actually knows about the subject but rather how fast the student can write. It doesn’t give a comprehensive view of the knowledge the student has acquired by doing the work and has more to do with the individual’s ability to think quickly.

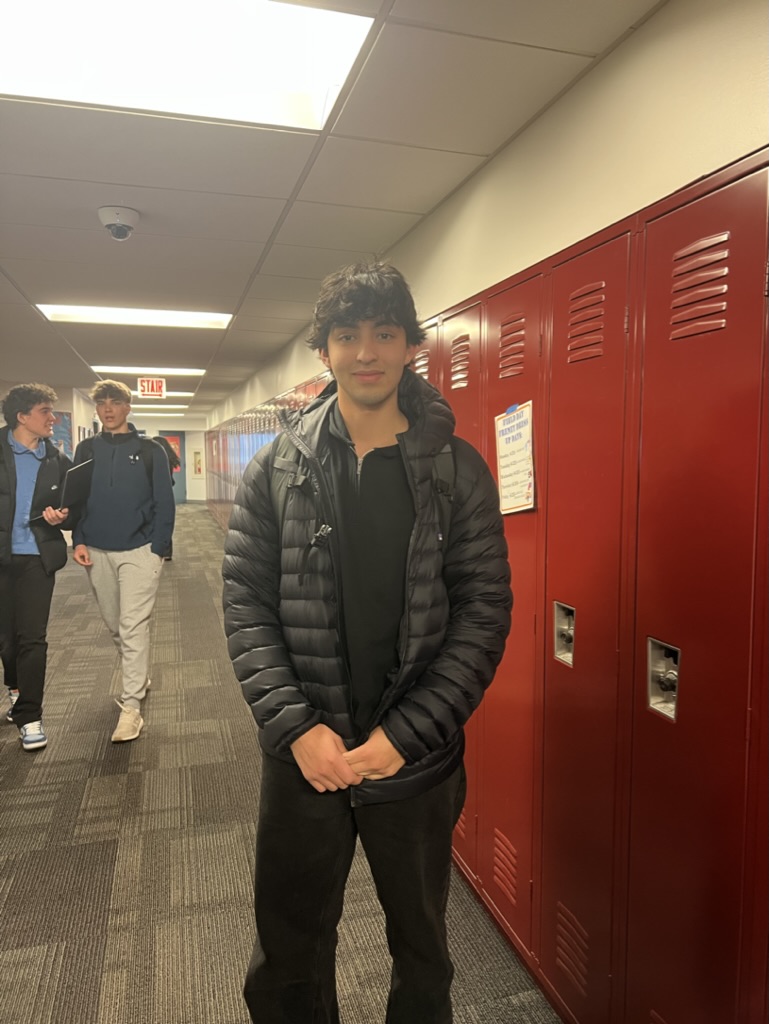

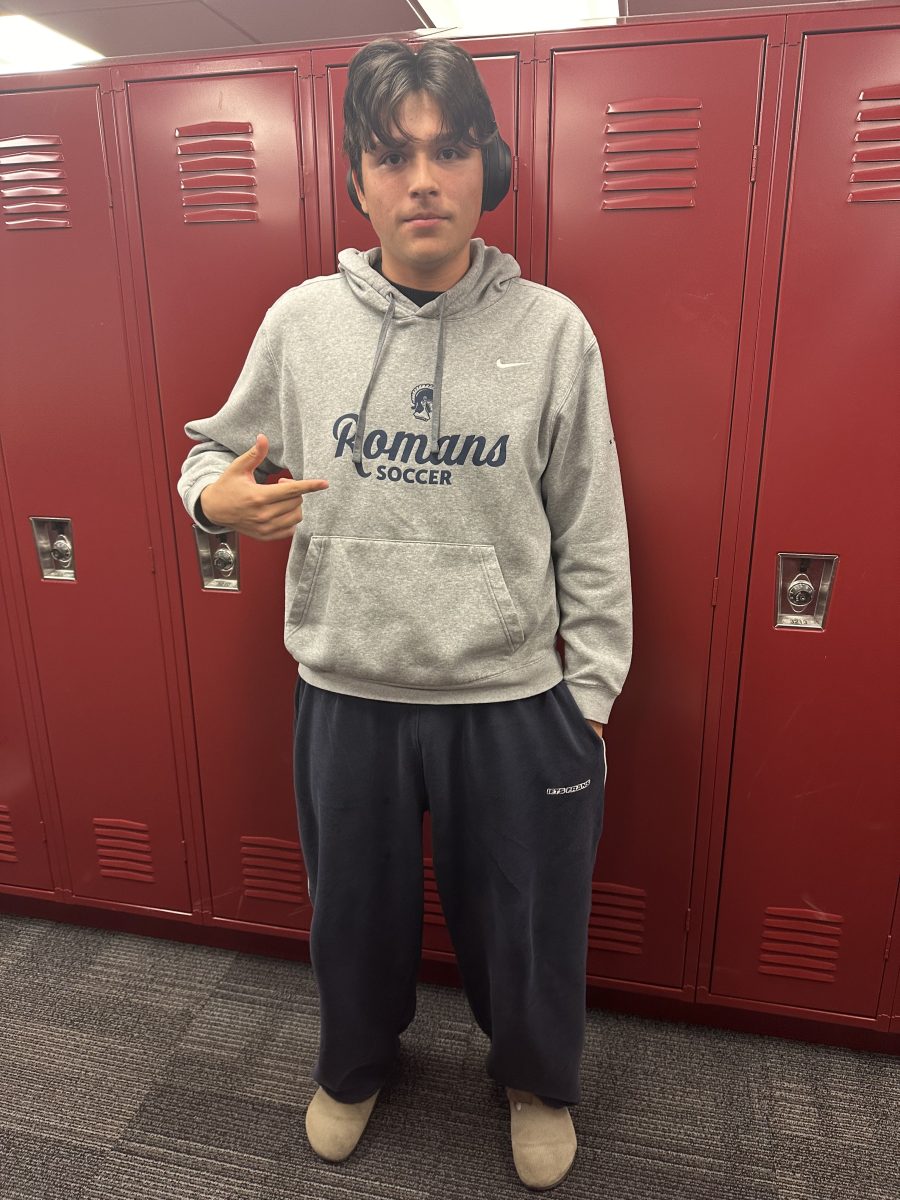

Junior Finn Kelly has written his fair share of in-class essays, most recently, in his U.S. History class, where students got 40 minutes to respond in 300 words to an unknown prompt. Students are assessed on many skills and have the opportunity to earn honors credit based on these essays, which, during the first quarter, made up the majority of assessments. Finn said, “The history curriculum is pretty well rounded.” Although, he added, “The analytical paragraphs are unnecessarily stressful and seem to me as more of a drill of concision or speed than a true knowledge of the material.”

Upper School English teacher James Joyce doesn’t like to use in-class essays in his classes. He said, “It is mostly because of the amount of stress it induces in the student, how much post-writing clean-up there can be afterward to make sure the argument (et cetera) is clear, and due to my thought that such issues can outweigh—for my needs—the potential benefit of seeing how a student performs under pressure.” He also said that some teachers who assign in-class essays frequently can see a benefit from them, but for teachers who aren’t focusing on consistently assessing students in the classroom, they can lead to more panicked writing than a clean-cut essay.

Students are already under a lot of stress and pressure—that is the nature of school—but, in anticipation of in-class essays, students’ nerves leading up to the class period can impact their performance. It is hard to do your best work if you are anxious days in advance.

Upper School history teacher and co-department head Ernesto Cruz offered insight into the reasoning for embedding analytical essays so deeply in the curriculum, specifically history courses. He posed the question, “What is a test but an in-class timed assessment of your knowledge and abilities?”

Mr. Cruz said he felt as though in-class essays are an effective tool for grading, adding, “We are trying to get a more authentic assessment of a student’s abilities. Revision is absolutely a skill and an ability, but we are not always assessing revision skills.” Although teachers will sometimes grant revisions, the revisions don’t have much of an impact on final grades. Mr. Cruz also said, “One assessment type, no matter what assessment type, is never going to give you a holistic picture.” For juniors, in-class essays will make up 50% of graded work by the end of first semester.

So are there any alternatives to in-class essays?

Sophomore Carmen Quinones has been hard at work writing in-class essays this semester, but a little differently. In her English class, after her teacher left comments and suggestions on her initial writing, she got plenty of time to meet with him and revise her work before it was assessed for a grade. Carmen said, “For standards-based, I think having more time is really helpful because when you’re under a deadline for a passage analysis you forget grammar things or little things that could make it better.”

With her English essay, knowing that she had the opportunity to go back and revise her work alleviated Carmen’s stress, so she could write knowing that whatever she had already written wasn’t going to be looked over for a grade but more so to help her see the places in which she could improve and better herself as a writer. That approach is great, because the teacher can get an idea of how a student writes under pressure and with limited time, but they can also focus on the more important aspect, which is helping students become better writers.

Another option is to switch to the classic take-home analytical essay in which students are able to be more intentional with their wording and can demonstrate to the teacher their hard work and their true writing ability. Over time, working on writing individually in a stress-free context could also help students develop quick thinking and writing skills.

While helpful in assessing certain skills, in-class essays create a lot of stress and don’t accurately depict the true abilities of individual students. While some teachers like Mr. Joyce have started moving away from those sorts of assessments already, hopefully, it becomes a wider sentiment. In-class essays can hurt a student’s grade, even if they are excellent writers when allowed more time. Here’s to hoping in the coming years teachers opt for assessment styles that better represent students’ writing abilities as a whole and move away from, as Finn put best, an assessment style that “greatly reduces what a student can produce.”

Amanda Valenzuela (’23) is excited to be a staff writer this year. Her favorite class subjects are English and history and she loves to write about current...

Cade • Jan 16, 2025 at 8:44 am

I love this I am trying to write an essay as to why schools should get rid of essays

Matthew Kotcher • Dec 16, 2021 at 9:54 am

Great synthesis, Amanda!