The College Application Process is Spinning out of Control: Here’s a Solution

This year, an assortment of factors, including widespread test-optional policies, extra free time from sitting at home, and pandemic-related uncertainty, led to a deluge of applications at top universities.

Upper School college counselor Alexandra Fields said that seniors at Latin, as well as at peer institutions, submitted more applications per student this year. She pointed out that students’ inability to visit colleges and “hone in on what they were hoping or wanting, or maybe even a first choice” also played a factor, leading students to take the approach of “casting a wider net” in hopes of visiting schools in the spring.

Additionally, the switch to online marketing and info-session allowed colleges to reach a wider variety of students. Many students applied to schools they would not have otherwise considered due to the efficiency of logging into a Zoom session for any and all schools.

Some schools, like Colgate University, with a hefty $60 application price, saw a 100% increase in applications, an unprecedented rise for a single year. Harvard’s single-choice early action—with a $75 application fee—saw a 57% increase in applications. The eight Ivy League schools pushed back the date they will announce admissions decisions to April 6 as a result of significant increases in applications.

Conversely, less selective colleges such as those in the State University of New York (SUNY) system saw a 20% decrease in applications, causing concerns around their ability to sustain themselves. According to The New York Times, applications to Cal Poly Pomona are down 40% from last year.

According to Inside Higher Education, the total number of applications from high school seniors through the Common Application system increased by 9% this year. The number of unique applicants only increased by 1%, however, signaling a significant increase in the number of applications per student.

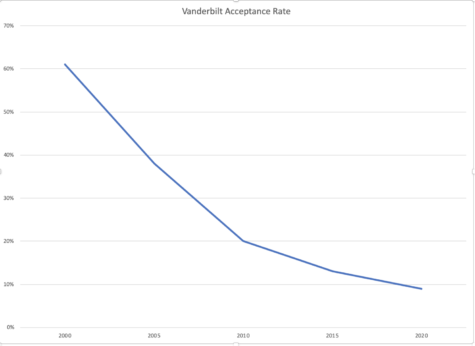

While these statistics may seem shocking, they are a part of a more sustained trend of increased applications to top schools. Platforms like the Common Application and the Coalition Application make it easier for a single applicant to send in applications to as many schools as they would like instead of filling out separate applications for each school. Additionally, private institutions have learned to better market their financial aid programs to attract well-qualified low- and middle-income students who would normally go to state schools. According to Ms. Fields, “The more selective private institutions have become more socioeconomically diverse in the last 20 years or so.”

Top schools have an incentive to decrease their acceptance rate every year, and to do so, they rely on receiving more and more applications each year—a system that is unfriendly and hostile to student’s mental health, to say the least. Most seniors have seen the endless emails from universities begging students to apply, only to ultimately reject those students. Whom does the process serve? Certainly not students who feel pressure to send in an unsustainable and expensive number of applications in the hopes of hitting the jackpot at one school. Not admissions teams who have to read thousands of applications.

Given that there is a correlation between low acceptance rates and higher rankings, arguably the greatest beneficiary of this system is U.S. News and World Report, because they have found a way to capitalize on the college rankings fever as schools jockey for higher positions on the lists.

Colleges have made changes in response to the increases in applications, recognizing that their admissions yields (the percentage of admitted students who accept their offers of admission) may decline in an increasingly competitive environment. Changes include admitting more students through Early Decision, adding Early Decision II, adding Early Action, accepting more students to account for those who will turn down their offers, and using waitlists more.

“The thing is, as long as schools can continue to meet their enrollment numbers, I don’t think they’re going to feel particularly inspired to change, because they like the increase in applications because it makes them look more selective,” Ms. Fields said. While schools are incentivized to keep the current system to decrease acceptance rates, when will enough be enough?

And at the end of the day, is “selective admission process” even the right term? Or is it really just a lottery in which admissions officers must pick from equally qualified candidates with no clear rhyme or reason?

Every year, the selectivity of schools increases and the number of schools students apply to also increases—a flywheel that spins faster and faster with every admissions cycle and is bound to break. Whether anyone likes it, the system must change.

Consider the medical school application system, the QuestBridge application system, and even the Chicago Public Schools Selective Enrollment application system. These systems are ranking-based. Each applicant ranks their schools by preference, and the system matches each student to the first school in their ranking that they are accepted into. In this proposed system, students would fill out only one application per grouping as opposed to writing unique essays for each school, and that single application would be read once and then the applicant would be matched. Senior Charles Mitchell, a QuestBridge Scholar, said he found ranking his schools to be the hardest part of the process, but regardless, “For people who are certainly sure that there’s a set number of schools that they would be so happy at, the ranking system is perfect.”

To make this process more digestible, it can be implemented in groupings of similar schools, whether by geography, a similar level of “prestige,” or other factors. For example, the Ivy League and the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) would be easy groupings. In this case, these groupings happen to be the sports leagues, but the schools also share similar academic philosophies. Other groupings could be geography-based; perhaps there could be a group of Southern private schools consisting of Duke University, Vanderbilt University, Wake Forest University, Emory University, Tulane University, The University of Miami and Rice University.

A ranking system would also allow students to show their passion for their top schools. “Right now,” Ms. Fields said, “the biggest way that a student can express that a school is top of their list is to do a binding early application.” A commitment to a school through early decision also means a commitment to whatever financial package the school offers. Thus, early decision “is not really in the cards for everyone.” A ranking system, according to Ms. Fields “would give a way for students to express their level of interest without necessarily making that commitment.”

The ranking system, however, is not without its disadvantages. The act of ranking schools, especially at the beginning of the process, is undoubtedly challenging. More important, though, is the financial aspect in preselecting schools. As Ms. Fields explained, with the current system, students can evaluate their choices in the spring and decide which school offers the best financial package. A ranking system would have to ensure that students get the best chance at their top school while also making sure that they have a plethora of financial options at the end of the process.

While the prospect of receiving an acceptance from only one school in a grouping may seem daunting, at the end of the day, students can only attend one school. Instead of choosing between multiple schools in the spring, students could preselect where they want to go beforehand. The pros of this system far outweigh the cons. It’s more cost-effective, students wouldn’t have the stress of writing individual applications, admissions officers would read fewer applications, and in the end, it’s fairer than our current system, which essentially operates as a lottery. Students would be more likely to end up at their preferred schools, and schools would end up with students who want to be there.

Ashna has been writing for The Forum since freshman year, and it remains one of her favorite activities. She also enjoys working out, making...