Will Slater The email attached below was sent to various parents under the address [email protected], calling upon its audience to fight these changes in the new physics unit, said to be indicative of greater flaws within Latin’s curriculum. It was, by all reasonable accounts, a flawed letter. People who really want to be heard, who truly want change, don’t hide behind anonymity. Words lose their value and opinions lose their dignity when not backed by a name. Simply put, criticizing hardworking teachers behind a fake email address is cowardly. The class is depicted in such a limited way that one has to wonder if the sender of the email even really understood the nature of the unit. “If you hide your ignorance, no one will hit you and you’ll never learn.” -Ray Bradbury Writing letters like the one sent to parents is not how adults handle their problems. That said, the questions presented in the email are ones worth asking, and as a trusted voice in the school, the burden of acting responsibly falls on the shoulders of the Forum. And that is what this article intends to do: get every side of the story, understand the implications, and truly question how we handle race at Latin. It’s funny how sometimes the only ones willing to act like adults are kids. Before reaching a conclusion on whether or not the unit should have been handled the way it was, we must first understand both student and teacher perspectives on the class. As summarized in a previous article, the unit was one with the intention to explore “power dynamics, systemic racism, white privilege, and the shortage of people of color and women in the field of science, especially physics.” In class, this looked like the survey included in the email, paired with discussions and readings. Students were mixed on the issue, with some repeating, albeit in a less immature way, sentiments in the anonymous letter. Many felt that the unit had no place in the context of the class, and detracted from the more pressing and culturally relevant topic: circuits. The opinion voiced in the letter and echoed by students, that physics was more pertinent in that class, seems shortsighted. In college or beyond, it’s hard to imagine a month of circuits being more useful than knowing how to talk about race. Some students counter that the place for such discussions is in history or wellness classes. The section of wellness for freshman that covers race and identity is only six class periods in an overcrowded room, where in my experience uncomfortable laughter is more common than honest discussion. It’s hard to fault teachers for this, but it’s easy to fault the structure of the class. Smaller groups, more time, less frivolous videos from the 90s, and a more inquiry-driven curriculum are needed. History classes teach race but mostly do so in a specialized way, where the focus is on narrative and how race fits. The kind of self-analysis that was asked of students in the physics class doesn’t exist here. Science, despite how it is so often taught, does not exist in a vacuum. Race plays a role in the history of science, so a physics classroom isn’t such an inappropriate venue. Mr. Legendre makes a point early in the year of telling chemistry classes that most of the scientists who made the discoveries we would go on to talk about were white men, since at the time of the work we were studying, the intellects of women and racial minorities were not respected or even acknowledged. It’s important and powerful to recognize this, and the effort to take the idea a step farther makes sense. The issue with race education is that conversations about race—especially in a classroom with many white kids and few kids of color—can be uncomfortable. A lack of comfort is at times required in school, but it can’t be that kids of color in particular feel alienated. There needs to be a concerted effort to reach out to parents and students, maybe even the Diversity and Equity Committee or the Student Academic Board, to plan a curriculum about inclusivity that is in fact inclusive to all. Questionnaires, though asking interesting and important questions, are hard to process. It’s hard to be honest with oneself, especially when it is commonly believed that teachers will see and perhaps judge the answers that are put down. Three scenarios are common: upon answering the questions a student finds himself to be perfect, is embarrassed to find that he is racist, or more likely he doesn’t understand the meaning and weight of the questions. In all three situations, there really isn’t anywhere to go as far as self-evaluation. The letter came at a poor time for the administration and board of trustees, as we as a school recently faced a strenuous accreditation from The Independent Schools Association of the Central States (ISACS). As explained by Mr. Dunn in an email to faculty and parents, the school did very well, but the ISACS team called for improvement in the field of diversity and inclusivity. What does this mean? It means going beyond merely having the “proper” number of kids from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, to truly making the school a place where everyone feels comfortable, heard and respected. The ISACS report revealed that Latin is not always successful enough, or for that matter isn’t trying hard enough to foster a culture of inclusivity and equity. The aforementioned email sent by Mr. Dunn was an impressive one, taking personal responsibility for shortcomings and promising to improve moving forward. It takes a lot for an institution to admit flaws, but it takes more for one man to do so; it takes a true will to improve. The board of trustees, headed by parent and alum Vince Cozzi, sent an email to parents in response to the feeble, anonymous parent letter. Mr. Cozzi and the board began by saying that the opinions in the letter sent don’t reflect the Latin faculty or staff, before rightly explaining that we don’t handle problems at Latin in such inappropriate ways. The board’s note progressed to the ISACS review, and the school’s action to improve. We will, in coming weeks, be analyzed by an independent organization that hopes to find flaws and direct change at Latin. Numerous students, teachers, faculty, and parents will be interviewed as part of this process. As with the letter from Mr. Dunn, it’s hard not to applaud the board and administration’s efforts to improve, sacrificing money, time and even pride to do so. These efforts should yield positive results, but the students and faculty still face a tremendous task on the horizon, one that cannot be tackled by anyone outside Latin. Progress won’t come with anonymous letters criticizing, for to criticize and not offer solutions is to offer half a thought, the easier half at that. Growth will come when more departments follow in the footsteps of the science department, but don’t make the same mistakes. For now though, we need to take a breath, and not scapegoat our struggles as a community on a few well-intentioned teachers, or our head of school. Below is a copy of the anonymous email for reference:

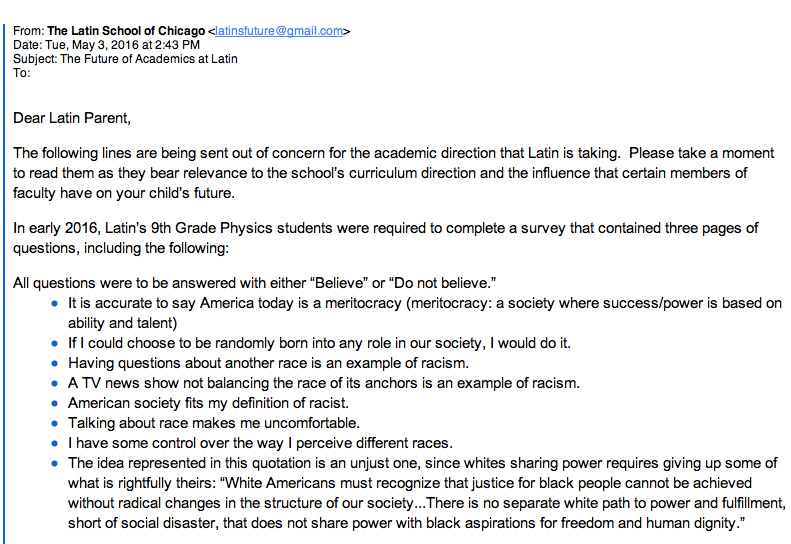

Dear Latin Parent,

The following lines are being sent out of concern for the academic direction that Latin is taking. Please take a moment to read them as they bear relevance to the school’s curriculum direction and the influence that certain members of faculty have on your child’s future.

In early 2016, Latin’s 9th Grade Physics students were required to complete a survey that contained three pages of questions, including the following:

All questions were to be answered with either “Believe” or “Do not believe.”

- It is accurate to say America today is a meritocracy (meritocracy: a society where success/power is based on ability and talent)

- If I could choose to be randomly born into any role in our society, I would do it.

- Having questions about another race is an example of racism.

- A TV news show not balancing the race of its anchors is an example of racism.

- American society fits my definition of racist.

- Talking about race makes me uncomfortable.

- I have some control over the way I perceive different races.

- The idea represented in this quotation is an unjust one, since whites sharing power requires giving up some of what is rightfully theirs: “White Americans must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society…There is no separate white path to power and fulfillment, short of social disaster, that does not share power with black aspirations for freedom and human dignity.”

While questions of race must be asked and reflected upon, do they belong in a physics class? More importantly, if Physics class time is dedicated to such tangential topics, will our 9th Grade Latin students be prepared for collegiate rigor? If this is happening in a Physics class, in what other classes are we straying off the intended (and expected) topic? Parents, please answer “Believe” or “Do not believe.”

Please contact Randall Dunn and the Board of Trustees for the communication that Latin sent out POST survey and if you would like a copy of that letter or survey or have any questions about Latin being “life prep” rather than “college prep.”

]]>

zmcarthur • May 29, 2016 at 11:19 am

Powerhouse article, Will. My favorite paragraph: “Students were mixed on the issue, with some repeating, albeit in a less immature way, sentiments in the anonymous letter. Many felt that the unit had no place in the context of the class, and detracted from the more pressing and culturally relevant topic: circuits. The opinion voiced in the letter and echoed by students, that physics was more pertinent in that class, seems shortsighted. In college or beyond, it’s hard to imagine a month of circuits being more useful than knowing how to talk about race.”

I hope you help prioritize extending these conversations throughout the school in your role as junior prefect next year. In my opinion, diversity and equity work – along with other non-academic parts of high school curriculum – shouldn’t be confined to solely history classrooms, or wellness, or even science – it should be integrated into the hallways, assemblies, grade level meetings, clubs, and advisories. There’s nothing more important than you students being exposed to and challenged to argue these issues in different contexts BEFORE you go off to freshmen dorms, where inexperience discussing these topics, wherever you stand on them, will be seen as a sign of closed-mindedness and immaturity.