The Upper School has implemented a complete phone ban for students during the school day, beginning this year. This policy is an updated version of last year’s, which required students to deposit their phones into designated boxes during class, and it comes as other Chicago high schools step up their respective phone policies. In cracking down on phone usage, Latin aims to strengthen the community and mitigate in-class distractions.

If students are seen on their phones between 8 a.m. and 3:20 p.m., faculty will confiscate the devices until the end of the day. On the third infraction, a parent must pick up their student’s phone.

University of Chicago Laboratory Schools has a similar policy to Latin’s, which Lab began this year, and was one of the schools that inspired Latin to move forward with its own ban. Kian Ladner-Huq, a sophomore at Lab, said, “Lab’s current cell phone policy states that no phones [or] iPods can be on your person during school hours. Lab said that they instituted this ban to improve student interaction and help people focus.”

Latin’s policy last year, which targeted distractions in class, was a small step to see if the school was ready for a bigger change. “That [policy] was a real success,” Upper School Director Nick Baer said. “It was only positive things.” Similar feedback from faculty and families pushed the Upper School to instate a complete ban.

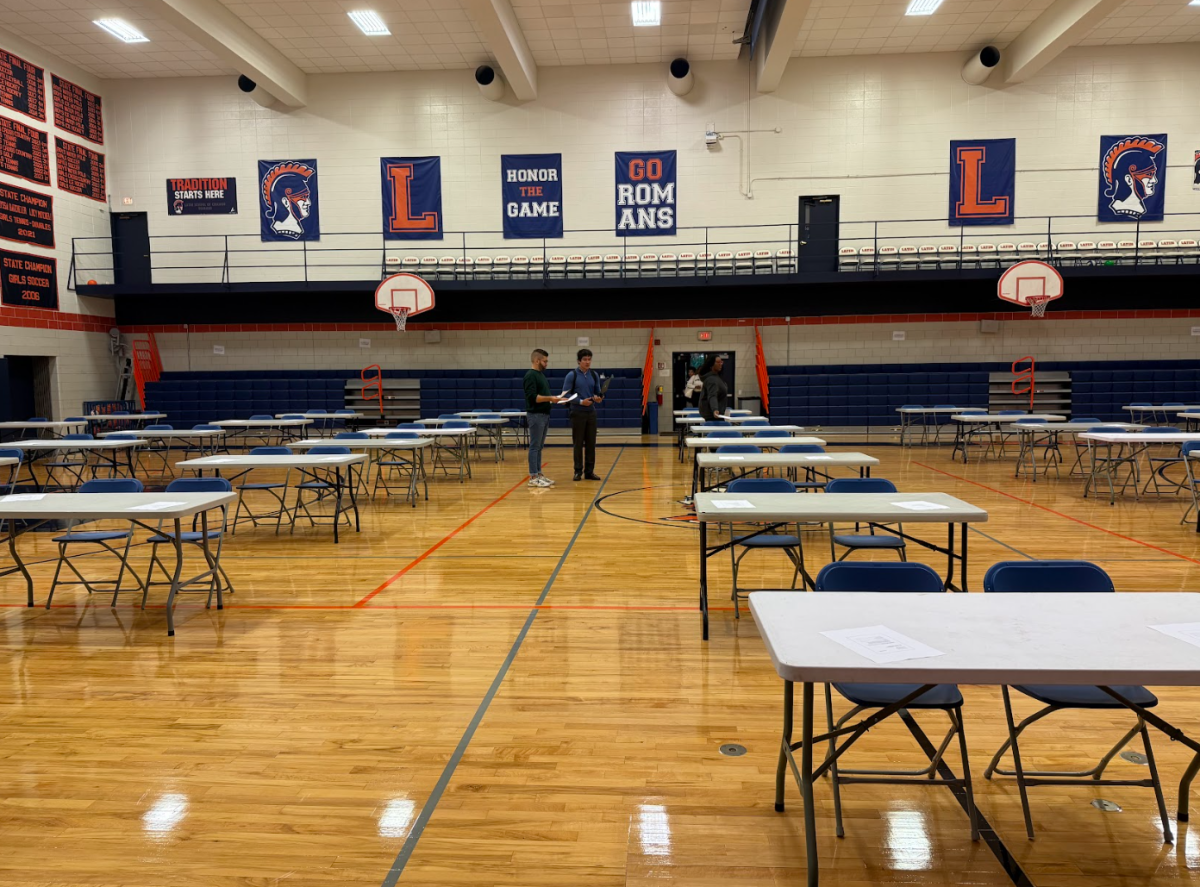

Latin’s sense of community was also an enormous factor leading to the phone ban. “I hate attributing so much to COVID, but that changed this place, like it changed every school, and it took a while for people to want to go to things again.” Mr. Baer said. “[The Upper School Office] could be part of bringing some community back to this place.”

Specifically, administrators wanted to create a space where students can be more present and to reduce issues that arise from texting and social media use during the day. “My main hope for this rule was that students were connecting with each other more,” Mr. Baer said. “We can just focus on this community, our education, and each other.”

For junior Arden Brown, Mr. Baer’s hopes are coming true. “The phone ban forces me to engage with lots of different people that I normally wouldn't have, and it deepens my relationships with my friends and classmates,” she said. “I really enjoy that it gives me time to decompress during breaks, or lunch, and really recharge."

Mr. Baer offered insight into the kinds of community-oriented questions posed in the decision-making process: “Could we make a space where we're free of that pressure, or even just that instinct, that addiction to check your phone or go on social media?” Mr. Baer said. “Could we make a space where kids and adults are talking to each other more and connecting and being bored together?”

Science teacher Sarah Kutschke has been collecting phones at the start of class for five years. “I think it's about time that we get rid of the devices in school that cause such a huge, huge distraction,” she said.

Ms. Kutschke’s fears have statistical backing. According to The University of Chicago Press Journals, the mere presence of one’s phone can divert attention, thus diminishing cognitive capacities, including quick information processing, problem solving, and abstract reasoning—each of which is needed in the classroom.

Although the phone policy helps students focus in class, some faculty members, such as science teacher Jonathan Legendre, haven’t always been fans of the ban. “I was anti, purely for navigating the world,” he said. “I really thought that it was going to be too big of a hurdle for students to navigate the block schedule without a phone. I was also anti because I was really happy with the changes we made last year.”

Mr. Legendre ended up changing his mind after seeing the ban in practice. “I really like the idea that just not having phones means people don't have to worry about being recorded,” he said. Mr. Legendre also realized that small issues, such as not being able to scan QR codes or use a phone calculator if someone's calculator dies, were easy to get around.

While the ban’s goal is to strengthen community within academic and community spaces, many students are more concerned with getting to those spaces in the first place, as Mr. Legendre feared. Students seem adrift without their digital schedules: Lost freshmen roam the halls, and students pull out their computers in crowded hallways or surreptitiously check their phones to figure out where they’re going.

Senior Kelsey Riordan is one of many students facing these challenges without easy schedule access. “In the past three years of being in high school, [I’ve] really used my phone as a tool for executive functioning,” she said, “so being able to check [my] schedule, being able to plan things, and check my email quickly.”

But the US Office sees these issues, and they are working on solutions, such as bulletin boards and printed schedules to attach to bags or put in lockers.

Computers do have schedule access, as well as many other capabilities that phones do. However, Mr. Baer said, “That extra barrier of [not] taking out your computer or not having [your phone] right in your hand still makes a difference.”

Some students feel that this harsher phone policy isn’t entirely a step in the right direction. Kelsey said, “I think the phone ban is having a positive influence on community during the school day, but I'm wondering if it's going to have a more negative impact on community after the school day.” She worried that phone usage would bleed into after-school activities: “[People are] more likely to be on their phone during a sports practice, or they're more likely going to go home and want to be on their phones more because they weren’t on their phones all day,” she said.

Certain sports teams, such as the varsity girls golf team, have experienced other issues as a result of the ban. Captain Gillian Herman said, “Golf is ‘play it by ear’ depending on weather. It’s hard to know if a match is canceled because we don’t have our phones.”

Despite these concerns, Kelsey sees some benefits to the policy. “Eventually we'll have to manage our phone use in college and in the workplace, and I think it's better to learn those skills earlier on,” she said. “All of us, whatever generation, are still being consumed by screen time. Whether it's on the phone [or on] the TV, [screens are] just all around us.”

Mr. Legendre said he believes this policy will prepare students to regulate their phone use post-high school.

“We're coming off of a time when young students had unfettered access to screens because of a global pandemic, and so students picked up terrible habits about the ways they engage with screens,” he said. “Relearning good habits about not being tethered to a screen in an unhealthy way now can actually help you manage that privilege of having access to the screen when you get to college, because you know what it feels like to not need the screen in an academic setting.”

In a world where screens are omnipresent, Latin wants to reduce distraction as a result of—and overdependence on—technology. At the end of the day, it’s about bringing the community together. “We're not trying to make it super punitive,” Mr. Baer said. “We're trying to just make it more about a cultural shift.”