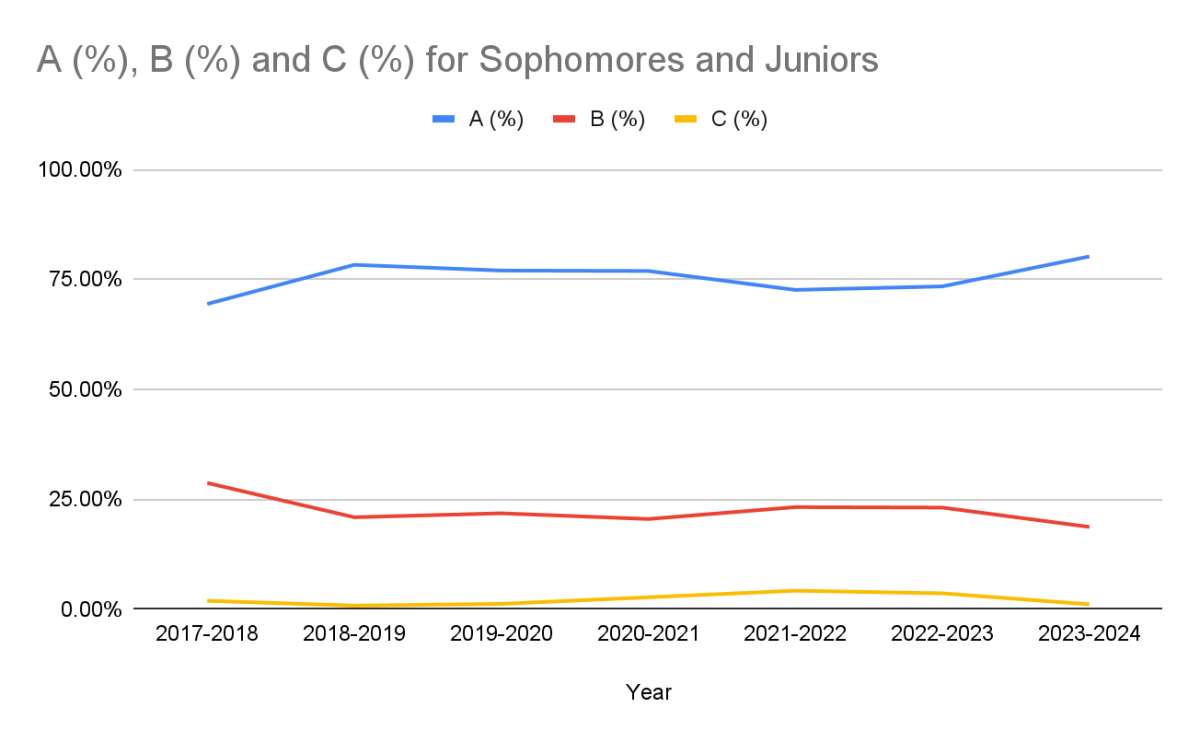

The percentage of students earning an A or an A- at Latin has increased from 69.4% to 80.2% over the past seven years. This sharp rise has sparked debate across academic departments on the reasons behind the jump and whether grade inflation is truly a problem.

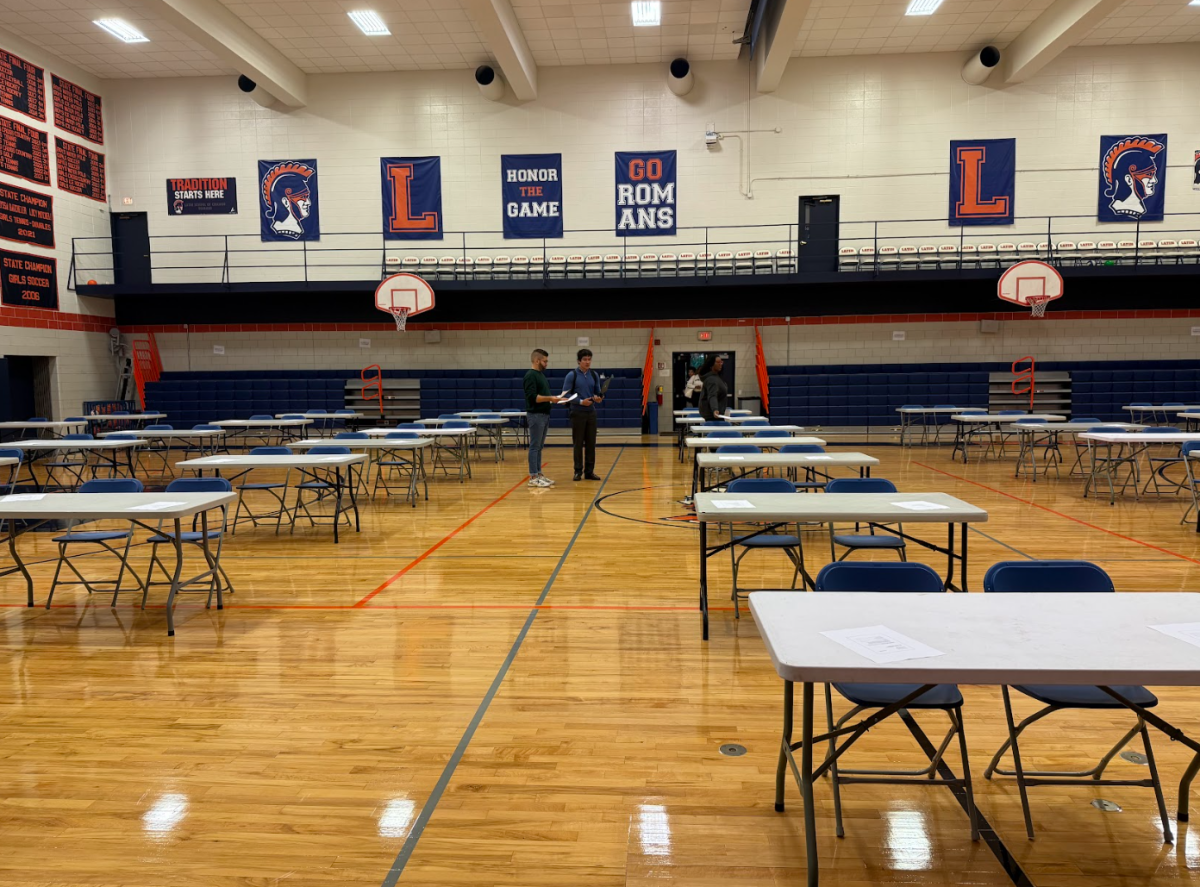

Latin publicly releases class profiles at the end of each school year, which contain grade distributions for the sophomore and junior years for every graduating class since the Class of 2020, except the Class of 2021. The data from these class profiles has been used to measure the aforementioned increase in grades.

An increase in the total number of A grades could be problematic if it reflects lowered grading standards instead of an increase in student performance, yet this distinction can be difficult to determine.

Junior Morgan Sirek said, “I think there’s still a lot of room for improvement that people might not be finding if they’re getting [an A] on all of their assignments instead of being really pushed to do better. I think that it’s just about trying to give incentives to people to strive to be even better than to be comfortable with wherever they are.”

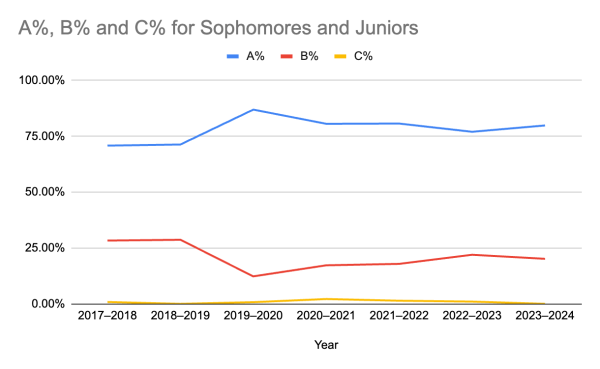

Out of all the departments, the English Department has seen the most upward trajectory in grades during the last seven years. During the 2017-18 school year, 61.7% of grades were an A or an A-, while during the 2023-24 school year, that percentage rose to 81.3%.

Part of the reason for this jump could be due to the Standards Based Assessments (SBA) grading system, which is meant to grade students on their mastery of certain rubric standards. Upper School English Department Chair Kate Lorber-Crittenden said, “Because we had to translate [SBA] to a transcript, more students were hitting mastery over time. There’s more room to grow and make mistakes, and it’s about where you are at the endpoint.”

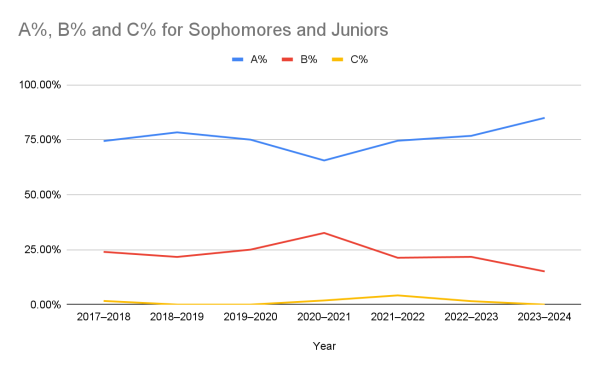

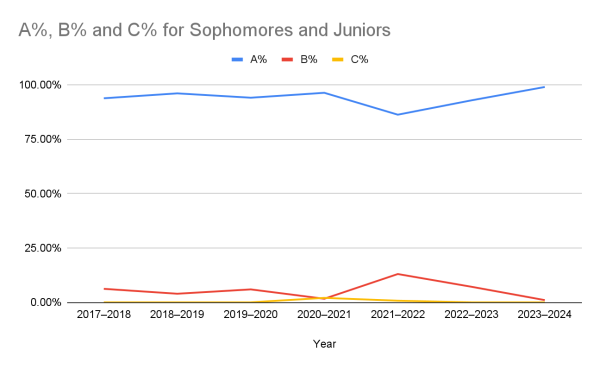

Another department that uses SBA and has seen its grades inflate is the Language Department. While not as substantial a shift as the English Department, the Language Department has seen an increase from 75% of students receiving an A or A- during the 2017-18 school year to 85% of students during the 2023-24 school year.

Upper School Language Department Chair Elissabeth Legendre said, “One of the goals [of SBA] is that we get students to a certain place by the end of the year, and we give students a lot of chances to show their knowledge and learning. We’re not holding it against students that they didn’t know something at the beginning of the year.”

Even though SBA can inflate grading outcomes, Ms. LC maintained that the English Department will continue to utilize the standards-based model in some capacity. However, they will make some modifications to their grading system: Starting next school year, rubric strands will be averaged rather than determined by mode in the English Department.

Ms. LC said, “The department all agrees that students are much clearer on the skills that [we are] trying to have them develop [because of the switch to SBA], and when they get feedback, they understand what it’s relating to and then how to apply that feedback. We don’t want to let go of standards, and we have just found a different way to calculate that in a way that still holds students accountable.”

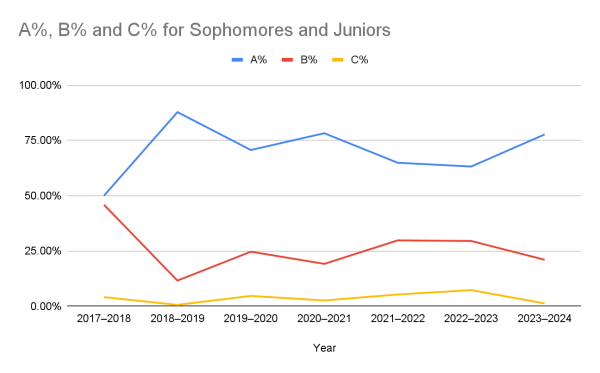

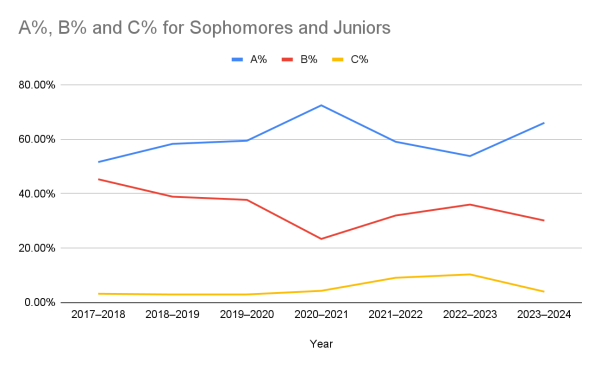

The Science Department also uses SBA to determine grades, though its grades have fluctuated greatly over the past seven years. Its overall A and A- distribution has increased from 50% during the 2017-18 school year to 77.7% during the 2023-24 school year; however, it spiked during the 2018-19 school year and dropped during the 2022-23 school year before ultimately rising again.

Upper School Science Department Chair Melissa Dowling said, “Our student understanding and mastery of the material, especially when we’re talking about small chunks of information, has gone up in the last few years.”

She also pointed out the effect that reassessments can have on a student’s grade. She said, “Because we give students extra chances, they have extra chances to learn and show mastery, and that would also correlate with a grade that goes up.”

Although grade inflation has not been as prominent in the Art Department, Upper School Visual Arts Department Chair Derek Haverland believes that a schoolwide increase should be seen through the lens of the COVID pandemic.

“There had to be reality checks coming out of COVID based on what students were expected to do,” he said. “In a very general sense, there was a lot of pushback from students on what was expected of them in terms of working differently being back in the building compared to what it was like working at home.”

Mr. Haverland also pointed out that grade deflation immediately after COVID could have resulted from students losing problem-solving skills. “A grade drop coming out of COVID was a part of trying to help students adjust to being back into the building. You’re dealing with students who, for a year or two, weren’t even considered high school level students.”

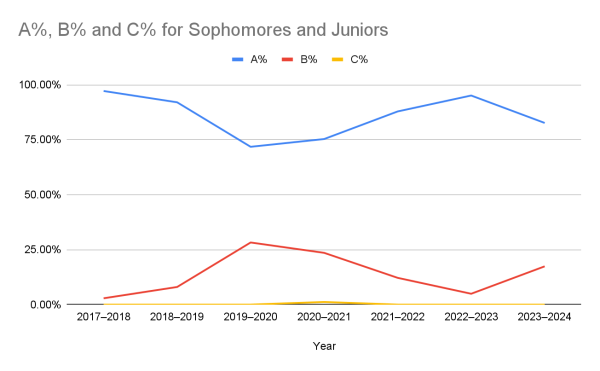

Upper School Math Department Chair Nichol Hooker also pointed out the effect of COVID on average grades. She said, “Grades initially were [inflated] early on in the pandemic, and then coming out of it, we saw a weakening in the core algebra and problem-solving skills.”

The data from the annual report supports Dr. Hooker’s point of view, as math grades peaked during the 2020-21 school year, in which 72.4% of students received an A or A-. After that year, grades dropped before ultimately increasing to 66% of students receiving an A or A- during the 2023-24 school year.

Another reason for grade inflation could be the changing perspective around what an A grade represents. Upper School History Department Chair Milena Sjekloca emphasized how A grades have increasingly become the expectation for students.

“Post-COVID, I definitely feel like there’s this notion or feeling among the student body that if you get a B, it’s like you failed, and that you can only get an A,” she said.

The History Department saw an increase in A or A- grades given out from 70.8% during the 2017-18 school year to 79.9% during the 2023-24 school year.

However, an overall increase in grades might not necessarily be bad if students are truly earning those grades.

Upper School Computer Science Department Chair Bobby Oommen said, “There’s no need to artificially form some kind of bell-shaped curve. If we truly feel that we’re assessing the right standards and kids are hitting those standards, then it [shouldn’t] cause any panic or alarm.”

Ms. Dowling pointed out that at the end of the day, no matter what adjustments we make to our grading system as a whole, there will always be room for improvement.

“There’s no perfect system,” she said, “and that’s what we all need to understand.”