Amid a wave of nationwide immigration crackdowns and growing political scrutiny of Chicago’s sanctuary city status, fear, anxiety, and frustration have intensified within classrooms and school communities. At Latin, some teachers have noted growing stress in the classroom, while students are increasingly responding through protest and advocacy.

Throughout his first 100 days in office, President Donald Trump enacted sweeping changes to U.S. refugee and immigration policy by suspending the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, pausing the Department of Homeland Security’s ongoing refugee applications, and instituting “stop work” orders that prevent resettlement organizations from supporting U.S. refugees. Additionally, the Trump administration terminated Temporary Protected Status for almost 350,000 Venezuelans, placing these individuals—who are lawfully permitted to live in the U.S.—at risk of being deported within the coming months.

These policies have also contributed to a climate in which isolated cases involving migrants are used to justify broad generalizations.

"[People] keep using these examples of certain cases—all of which are horrible—in which migrants have committed terrible crimes,” Pablo Arancibia, a Middle School Spanish teacher and Chilean immigrant, said. “[People] keep repeating these statements over and over again, using these statements to make blanket statements that ‘these people are bad.’”

In the midst of these concerns, some migrants are grappling with even greater struggles, as many have disappeared without a trace, leaving others uncertain as to their whereabouts. Mr. Arancibia, for example, frequently passes a warehouse that once housed hundreds of migrant families for months, but after Trump’s inauguration, every single one of them suddenly left.

“[I] don’t know where they ended up,” Mr. Arancibia said. He asked himself further questions to determine the potential locations of these families: “Some [migrants] must have left, but I don’t know where they went. There are so many people—where are they? Can they get detained? It’s so confusing.”

Federal immigration policies have also filtered into schools, where their effects are felt in subtle but significant ways, such as disrupted routines, student absences, and rising anxiety.

Victor Perez, an Upper School Spanish teacher and first-generation U.S. citizen, noticed a growing presence of immigration-related stress within his community, particularly with children.

“As the inauguration was coming, the amount of anxiety I saw in my community was super high,” he said. “I saw it amongst adults, I saw it amongst kids, I saw it all over the place. Particularly when we look at schools, one of the things that's important is when you're that anxious and have that much stuff on your mind, you can't learn.”

Some Latin teachers share that same stress, which was palpable during a recent full-school staff meeting, where Mr. Arancibia shared the emotional toll these policies have had on him and others. During the meeting, he said, “I want to acknowledge that some people, right here, right now, are super stressed out because we and our relatives can be targeted. I have to acknowledge that I have to carry with me proof of residence.’”

Students’ and teachers’ anxiety doesn’t just stem from legal concerns, but also from a feeling of dehumanization due to anti-migrant rhetoric.

“I am being called an ‘alien’ now. I’m no longer human, not even an immigrant, I'm an alien now,” Mr. Arancibia said. “An alien is a word that simply means that you just don’t belong here.”

As a response to these feelings of alienation and legal anxiety—which are felt by students as well—students across the country have begun taking action through protests and online movements.

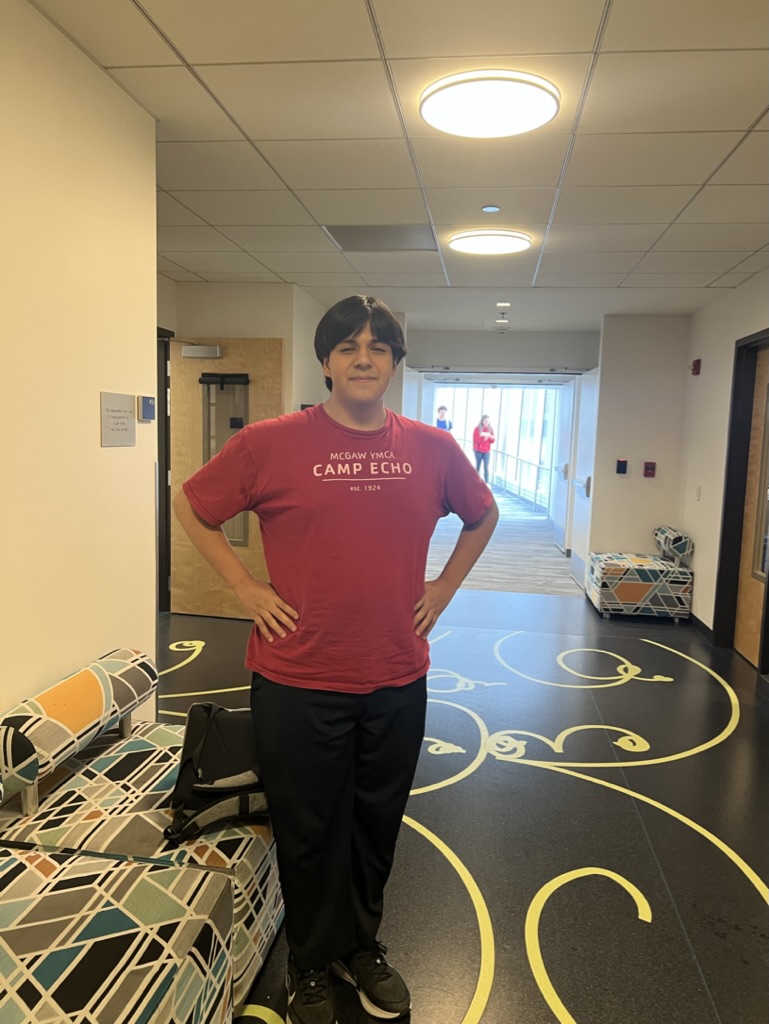

Leo Mendoza, a senior at West Chicago High School, attended a protest against Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in early February. “Just seeing everyone get together, chanting, not being afraid of anything, it really inspires others,” he said.

The protest, which began at a local gas station, consisted of many immigrant families and students—who learned of the protest through an online WhatsApp group chat—and ended up turning into a march, which lasted multiple hours until they reached downtown Chicago.

“Seeing everyone united really makes you feel happy,” Leo added. “For me, coming from an immigrant family, [the protest] really affect[ed] me because of my parents.”

Beyond the protests, Leo also shared insight into the atmosphere at his school, describing how fear has started to affect student attendance and how the administration is trying to respond.

“I talked to my counselor, and from what she told me, some kids are afraid and some kids are not coming to school,” Leo said. “Teachers and the principal are getting more involved. The principal told us they would start using student forms and flyers to help [with the anxiety]. If people needed help or were scared, there were phone numbers to call, [thus] making sure students were informed, as well as their families.”

Leo’s experiences are parallel to tensions felt throughout school communities, where both students and faculty are working through the fear. In fact, teachers must also learn how to express their emotions about recent policy changes, all while juggling professional responsibilities.

Mr. Arancibia, who typically teaches an immigration unit to his students, cited his concerns with addressing a topic so directly related to current events. “I’m already wondering, how am I going to talk about this?” he said. “I don’t want to paint this bleak image of what reality is, but on the other hand, if we don’t know, then we live in a bubble that isn’t reality.”

“I asked my class this question: ‘Can you prove right here that you are U.S. citizens?’ They all said, ‘No, none of us [can] prove it,’” Mr. Arancibia said. “[ICE] could literally ask anyone, but they will only ask certain people—it's like cultural profiling.”

For students struggling with such questions, many schools—Latin included—already have measures in place to ensure students have opportunities to share these difficult emotions.

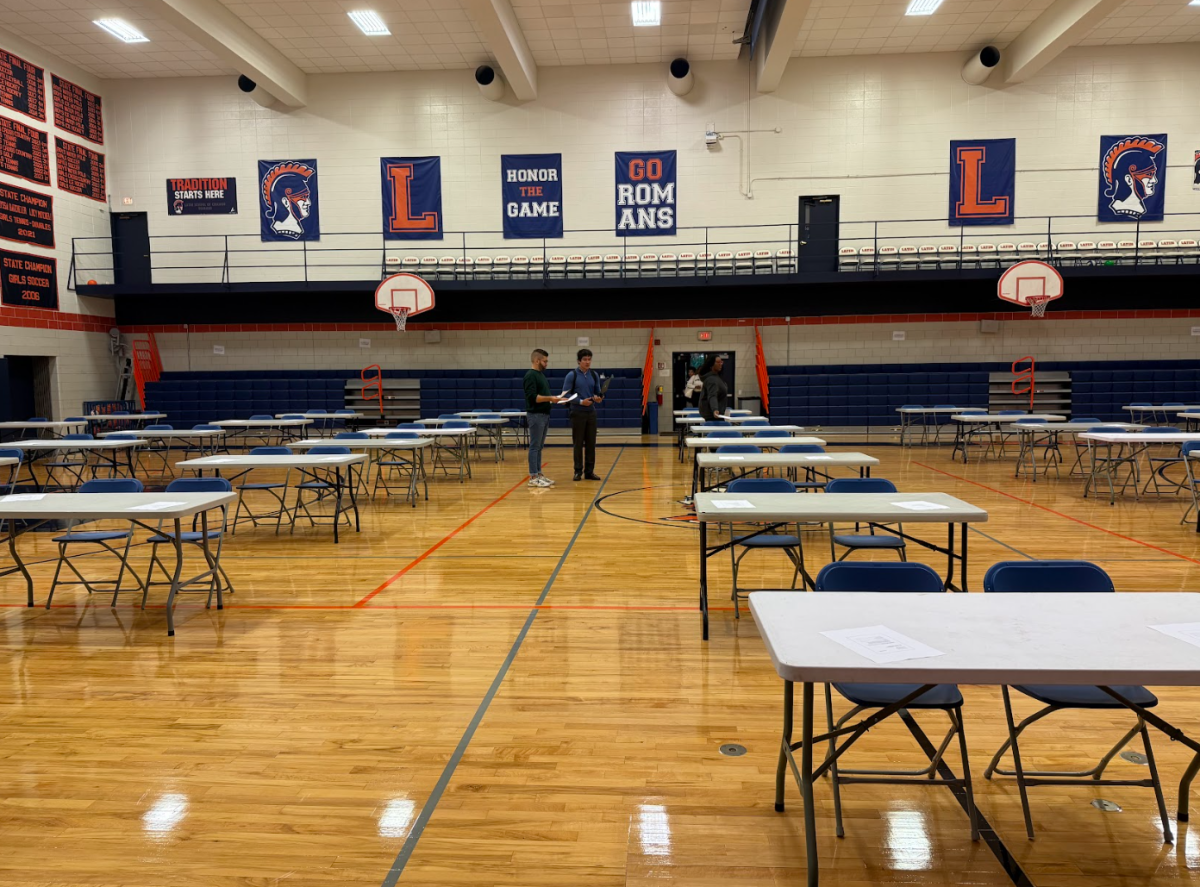

Mr. Perez said, “The thing that was particularly helpful for me was when we started building in affinity group time into our actual schedule, and creating space for kids to actually be able to say, ‘Hey, this happened to me in class.’”

At the same time, he acknowledged that more could be done to support students outside of the designated moments. “One thing that I think would be very beneficial [for Latin] is [to consider] what kind of programming [we are] doing in terms of social and emotional counseling for students who have families who are immigrants,” he said.

Looking to the future, the conversation extends beyond internal support systems, to how Latin—and similar institutions—interact and engage with Chicago. “Latin has the privilege of having ‘of Chicago’ in its name,” Mr. Perez said. “I think if you are going to fully live up to that title, you have to be able to build more and more relationships with communities outside of the ones that we typically go to.”