Navigating the Morillo Madness

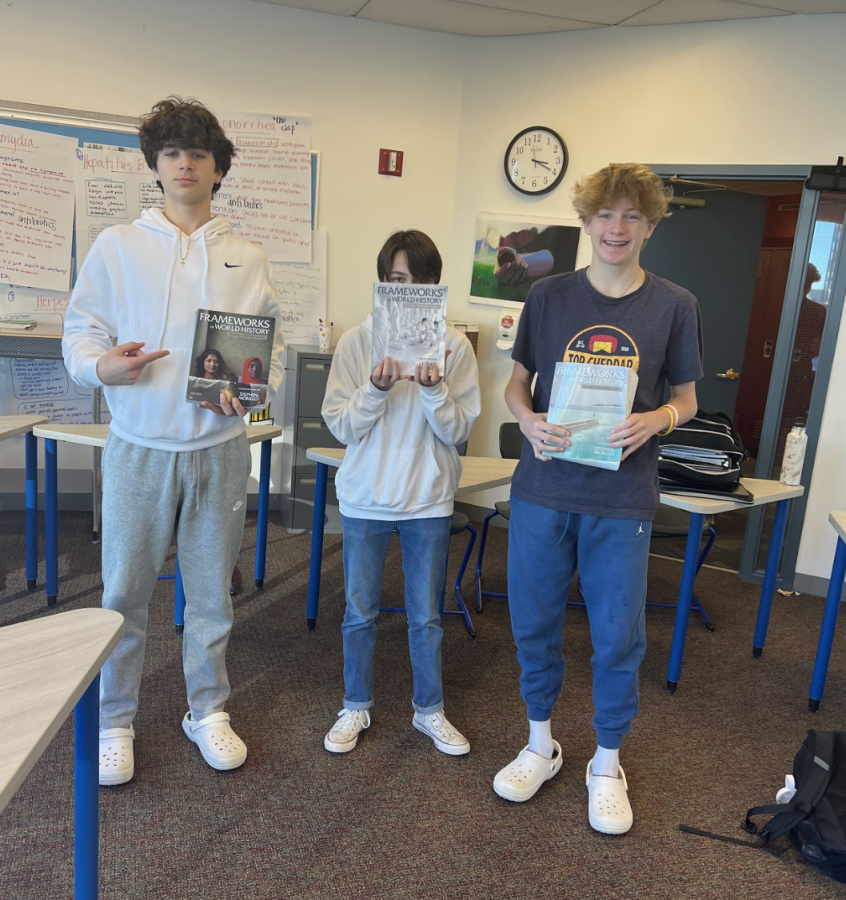

Freshmen Marc Abrahams, Connor Kernan, and Flynn Ogden stand with their copies of “Frameworks of World History.”

As proudly displayed on Latin’s website, 100 percent of students will take a different academic path through the Upper School. Indeed, there are few high school classes that all Latin students take—U.S. History, College Counseling, Ninth Grade Wellness, Global Studies Visual Art, English 9, and of course, Global Studies: Networks, Hierarchies, and Culture, the infamous freshman history course.

Core to the course’s curriculum is its textbook, “Frameworks of World History” by Stephen Morillo, often affectionately or disdainfully referred to using only the last name of its author. The textbook takes a thematic approach to world history, focusing on networks, hierarchies, and cultural frames and screens.

If those words seem like nonsense, you’re likely in the good company of a large portion of Latin’s freshman class; although Upper Schoolers will all end up on different academic paths, a sense of confusion at Morillo’s choice of vocabulary and flexible interpretation of what defines a shape to be a pyramid is a near-universal Latin experience.

However, before diving into what students think of the text, it’s important to rewind to the beginning of Morillo’s journey at Latin. Before Global Studies, all freshmen were required to take a history course called Global Cities, that is, until it was scrapped on the basis of its Eurocentricity.

History Department Chair Ernesto Cruz said, “Eight years ago we decided that we’re going to blow the whole thing up and start over, and what we had was a wish list of what the units would look like for the class.” Thus, the beginnings of Global Studies were born, and with them, the new course needed a textbook.

To find this book, the History Department, as Mr. Cruz said, “ordered essentially one of every [Advanced Placement (AP)] level world history textbook [they] could find.”

“[Some Upper School history department faculty members] read all these books, and in the end, there were two or three left, and then we just sat down and looked at them,” Mr. Cruz said. “Morillo wins out because it checked all of the unit boxes we wanted to check but it also wasn’t overwhelmingly Eurocentric. Morillo’s efficiency, because of its thematic nature, was absolutely a selling point.”

However, from the student perspective, Morillo’s thematic nature makes it not only efficient, but also quite dense. Freshman Charlie Wolin said, “I think he throws in a lot of unnecessary words to make himself sound smarter and it overcomplicates the text way too much.”

Additionally, the aforementioned flexible interpretation of a pyramid is a product of Morillo’s diagrams. The Agrarian Pyramid, a core social and political structure analyzed by the course, is often represented by visuals that, by later chapters, seem less and less pyramid-shaped. Freshman Vivian Lee-Yee said, “I think that it’s too wordy and hard to read, and the way he explains things—especially with diagrams—is very confusing.”

On the other hand, Morillo’s difficulty is very much by design. As Mr. Cruz put it, “We only started with college-level books for ninth graders because that was the charge we were given at the outset. As an AP level book, it’s got a Lexile score of something in the 1100s, which is something that ninth graders should be able to do here.”

Even so, the History Department has no lack of empathy for the struggle ninth graders have with the book. Mr. Cruz said, “There’s not necessarily the on-ramp to doing that much nonfiction reading at that high a level. This is just the price of doing business.”

Indeed, whether because of a lack of on-ramp or the textbook’s college reading level, Latin ninth graders often find “Frameworks of World History” to be much like the emails referenced in Grammarly’s now famous opening advertisement line: “wordy and hard to read.”

Freshman Sebastian Lee-Yee said, “I think [Morillo] uses an excessive amount of unnecessary vocabulary.”

This expansive vernacular is used throughout the book—whether describing Late-Agrarian Era England as a “monarchical oligarchy masquerading in the clothing of democratic mechanisms” or reincarnation as a “cosmic hierarchy of meat,” ninth graders often find Morillo’s diction and not-quite-comedic yet not-quite-monotonous tone perplexing, to say the least.

Freshman Morgan Sirek said, “The History Department says that Morillo is the best textbook that they could find, and I trust them on that, but I think that the way that he presents information is wordy and hard to understand, and it makes the reading less fun.”

Yet, the issues with the text go beyond its wordiness and high Lexile, as many students find that, as freshman Marc Abrahams put it, “Especially when it comes to more sensitive topics, [it] can word things really poorly.”

Freshman Lyla Granich said, “I think that Latin trying to adapt their history textbooks especially—and all the humanities classes—to more diverse viewpoints is very important, but at the same time, unless there’s actual systemic change occurring in all of these history classes, then just changing the textbook won’t really do anything.”

Certainly, as Latin continues to adjust its curriculum to represent as many genres, identities, and viewpoints as possible, the way Morillo fits into the framework of Latin’s history curriculum will evolve as well. Morillo’s adoption as a textbook hopefully can be a precursor of and accompaniment to this systemic change.

Although it may seem as though the book has garnered no fans, many freshmen indeed appreciate Morillo’s high level and unique content presentation. Freshman Gillian Herman said, “I think the book does a really good job of giving examples of the topics we’re talking about but not going too in-depth when we’re only talking about one place.”

Even the renowned wordiness and density of the text are appreciated by some. As freshman Miles Stagman said, “I’ve expanded my vocabulary massively.” Although ninth graders’ nightly readings have a steep difficulty curve, they also have a high reward in terms of thematic comprehension and reading level improvement.

Although the book may face its fair share of criticism, few things bring Latin quite so close together as “Frameworks of World History.” Whether it be the sophomores’ locker-bay shrine to the book or the freshmen who found the website of Stephen Morillo’s band and subsequently shared it with much of our grade, I can confidently say that Morillo is a near-permanent part of Latin’s cultural screen. Come June, I must admit I will be disappointed to not carry the text, in all its 1,000-page full-color glory, in my backpack each day.

Scarlet Gitelson (‘26) is delighted to be serving as one of this year’s Editors-in-Chief. Using her writing, she seeks to promote connection and discourse...

Jim Joyce • Feb 21, 2023 at 8:43 am

Cool piece, Scarlet. I just got my copy of Morillo a few years back. I enjoyed the representative quotations. I’m learning history with all the 9th graders! —Mr. Joyce