Latin’s New White Affinity Group

February 14, 2020

During affinity time on Friday, January 31, curious students and faculty crammed into room 501 to talk about whiteness. Historically, affinity block has essentially been a free period for white cisgender students, but on that Friday, students had the opportunity to change that. This meeting was, and the next few will be, open to students, faculty, and staff of all racial identities so that everyone had the opportunity to engage in conversations about whiteness as it operates today.

As race can be an uncomfortable topic of conversation, the group, led by Ms. L and Ms. Fields, first established discussion norms. Next, attendees discussed why talking about race can be uncomfortable, as well as the potential benefits of embracing such conversations. After watching a New York Times video of white people speaking about their racial identity, students and teachers broke off into small groups to discuss what they learned and what resonated with them. Between the full and small group discussions and times to reflect, attendees were given plenty of opportunities to look critically at how whiteness, while not traditionally discussed, is important to study when looking at societal racism.

While this was not the first time the school has toyed with a white affinity group, this was the first time there was a significant turnout. Senior Lulu Ruggerio, who attended the meeting on Friday, remembers, “When I was a freshman Ms. LC made an announcement about having a white affinity group and everyone was like this is crazy so no one went to it, I think it was even canceled it had a really low attendance rate.” Yet, three years later, Ms. LC tried again. Lulu recalls, “when she sent out that email and I’d heard a lot of good feedback from the workshop so I was really interested in the idea.” Other students must have felt the same way, as Lulu notes, “I was really surprised by the turnout.”

Ms. Maajid, Latin’s Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, agrees that the time for this group is now. She said, “As more is happening in the world we just thought it was really important to give that space and to be able to say that affinity time is important. We wanted to make it feel like it was important for everybody, not just one or two or ten types of people.” She explains that Latin originally started having affinity spaces because “it became very obvious that students of color and LGBTQ+ folk needed a space to come together so building that time into the community was really important.” The school has come a long way, where affinity groups used to have to meet before or after school, now, “Latin shows the importance of it by building it into the actual school day and not having it be something that feels like an add on.”

Latin students typically think of affinity groups as safe spaces for people holding marginalized identities, and Ms. LC challenges the community to think of affinity as something broader than that. At a breakfast the week after the meeting, she explained, “affinity is just a point of commonality, affinity happens all the time.” Anticipating peoples’ qualms about a white affinity at Latin, she admitted, “So why does white affinity feel different? Because it is.”

In many historical instances, white people gathering to talk about race has not been a good thing, and the group recognizes this. Thus, Ms. LC said, extra precautions need to be made. She said, “It needs to be a space that is confidential, but as people who hold dominant identities we have to be explicit in the work we do. It has to be facilitated.”

Right now, if someone were to walk into the learning commons during affinity time, they would see what appears to be unfacilitated white affinity. Lulu points out “the fact that we have an affinity block where people with these certain affinities all meet then there are white cisgender people in the learning commons for forty minutes straight and we’re all gathered. I was always thinking to myself this is weird.”

The new affinity group hopes that even if white students choose to keep their ‘free period,’ they do so thoughtfully. Lulu said, “it’s there for people to recognize the privilege that they have to have that free period,” and Ms. LC agrees.

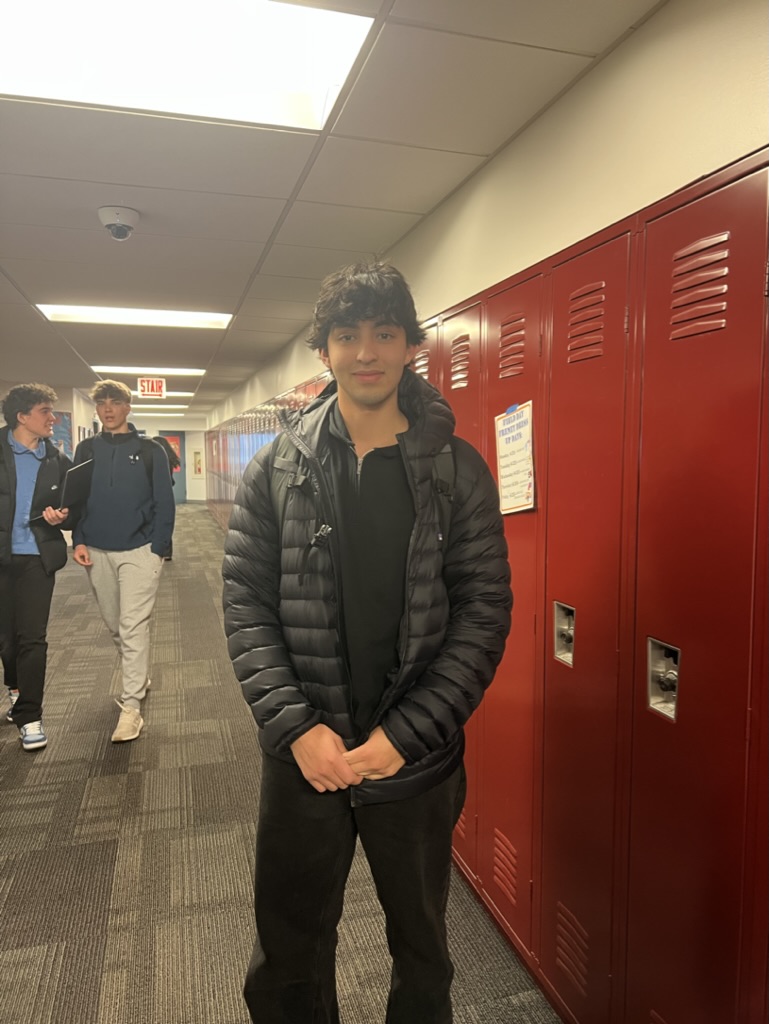

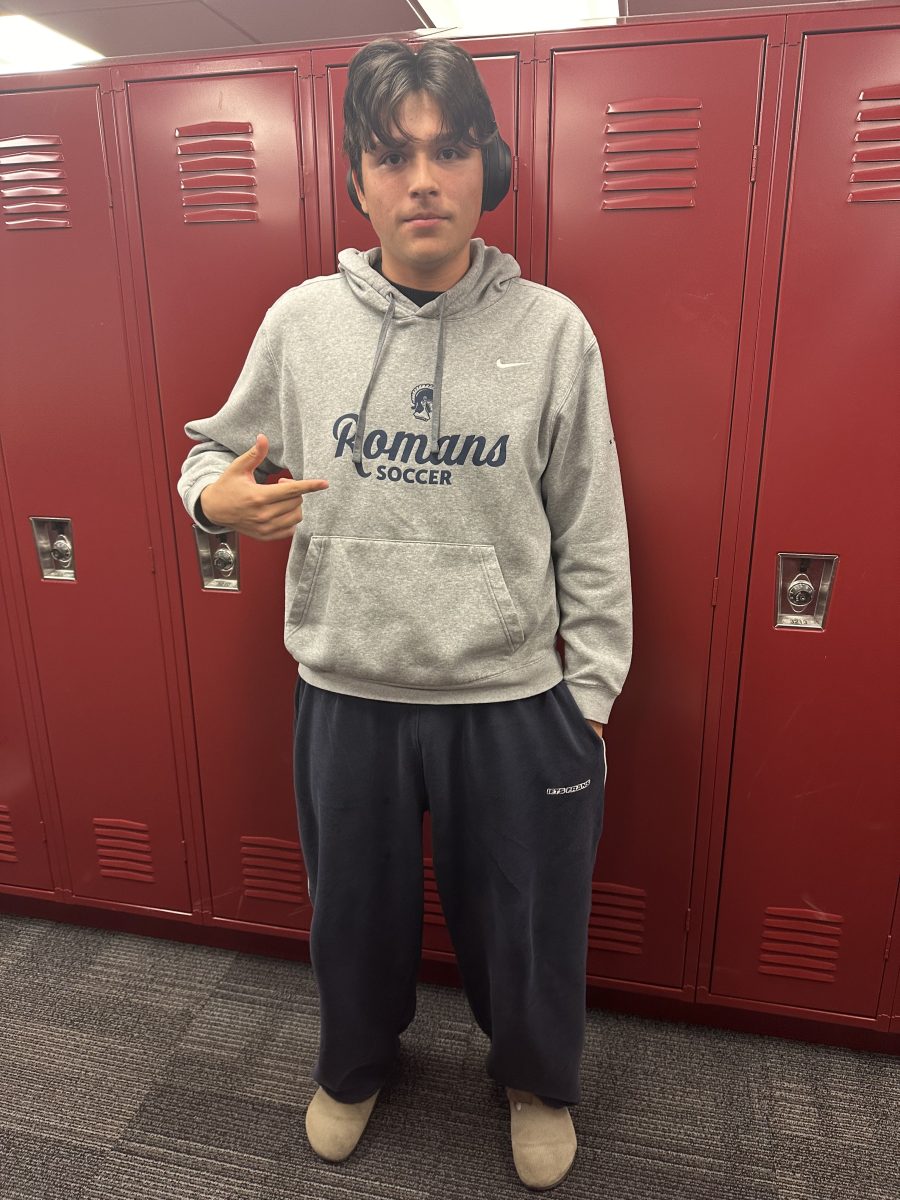

Senior Gabo Moreno, who also attended the workshop on Friday, agrees that it’s time for people to recognize whiteness as a racial identity. He identifies “as a multi-ethnic kid who’s a quarter Puerto Rican, a quarter Mexican, and a quarter Greek and a quarter German.” While he feels he has spent a lot of time at Latin talking about his LatinX roots, he said, “in other conversations, I always felt like my whiteness was ignored which I just felt was a little weird because then learning to deal with being multi-ethnic becomes a lot harder.” So, when he heard about the workshop, he was eager to join, saying “when I realized oh, there’s an attempt to talk about whiteness at this school, I thought that’d be a great time to start talking about a piece of my identity that often just goes unspoken.”

To talk about race, white people have to recognize that they have a race. Gabo said, “when we’re talking about race and racism everyone should be at the table to talk about it and I think it’s really hard to expect white people to come to the table and talk about it when they feel that they don’t really have a race.”

While the white “race,” along with any other “race,” is not biologically real, there is no doubt that it is real in how it shapes people’s daily lives. Thus, said Ms. LC, “The space is intended to reflect on and to understand how that identity shapes a lived experience.” She clarified, “It is not a space of shaming or blaming, but it is an expectation to recognize I have a racial identity and racism exists in the world, and I will understand how to combat that racism but I have to try to understand what it might mean to me.”

While everyone can speak to their own experiences, she said, “We can’t trust that we are always doing the right thing because white folks miss things a lot of the time.” Hopefully, this group will give people a chance to do some research so that they can better understand how racism operates in society today, because, as Ms. LC puts it, “if I’m asking people of color to teach me about race that’s really burdensome [for them].” But, it is imperative that we learn how to talk about race, as “If there are things I don’t know in a conversation where I’m really trying to engage and I have the best intentions, I can still engage in a way that puts a lot of pressure on people of color and makes them feel uncomfortable or maybe actually harms them.”

Hopefully, this group will give white students the space to engage in conversations about race so that they can have productive interracial conversations in the future. Gabo said, “if we can get white people together to talk about whiteness in a safe space and they can get comfortable talking about race I think that when we go to these bigger conversations that have people of multiple races together there will be a lot more white people that feel confident and secure in their own race and their own belief to be able to contribute in important ways.”

For now, the key is keeping turnout high so as to educate as many people as possible. Gabo notes, “seeing from the people that came to the meeting it’s obviously not reaching everyone and I think that the people that came initially are people that are already aware of this for the most part and are already doing ‘race work.’” As the year goes on, he said, “I hope to see it develop and I hope to see a lot more white people come because I think it’s really important for everyone to talk about their race.”

As far as affinity spaces go, Ms. Maajid expresses, “My hope is that anybody who wants to attend one feels comfortable doing so, feels safe doing so, and that at the end of the day, it doesn’t feel wrong to go or it doesn’t feel like you have to go because you’re so different.” When it comes to discussions around shared identities, whether that be racial, socio-economic, gender, or many others, she said, “the door is always open.”