Beware: Book Bans are Back

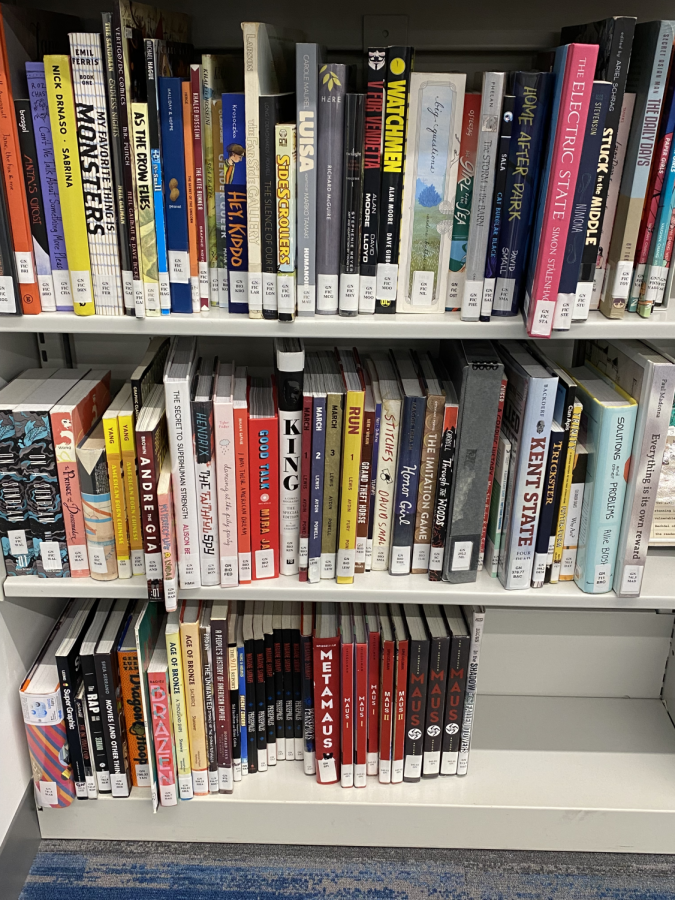

A snippet of Latin’s diverse book collection (including Maus, a book recently banned from eighth-grade language arts class in Tennessee)

Book banning is back. In January, book banning was thrust into the spotlight after a Tennessee school board voted to remove Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, Maus, from an eighth-grade language arts class on account of nudity and profanity. Ironically, it was the language of the text that some deemed too disturbing; the book details a prisoner’s actual historical experience at the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II. The attention-grabbing Maus debate comes amid a current surge of book banning contests throughout the country.

Christopher M. Finan, Executive Director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, reported to The New York Times that he has not seen this amount of book challenges since the 1980s. The Washington Post reported that in the past six months, book bans have been at their highest since the American Library Association (ALA) began collecting such information in 1990. From September 1 through November 20, 2021, there were more than 330 bans—and those are just reported cases, a mere fraction of the total cases.

Latin sophomore Maggie Zeiger thought this trend was worrisome. “I think the uptick in book bans is very concerning,” she said. “Banning books that illustrate different perspectives is incredibly dangerous for our country and has the potential to create an even deeper divide across America.”

While the issues surrounding the current surge may be new, book banning itself has been prevalent in America for centuries. Upper School librarian Gretchen Metzler said, “Historically and even now, it comes from a misguided place of wanting to protect people, but really what we see is a closing off of ideas and a restriction on what people have access to.”

In 1885, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was banned for profane language. The Harry Potter books were challenged throughout the 2000s because they “promote witchcraft; they set bad examples; and they’re too dark.” Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, often part of the curriculum here at Latin, was one of the most challenged books in recent decades due to “obscene, vulgar, and pornographic” language.

Typically driven by parents and community members looking to control content in schools or public libraries, books have historically been challenged on account of explicit language, violence, or concerns regarding content that may offend the moral ethos of the relevant time.

Yet today’s unprecedented spike in book challenges appears to be taking on more of a political tone, mirroring America’s current polarized climate and cultural wars. Current challenges focus on the exposure of young people to issues of race and gender. Maggie said that these political challenges “will further the political divide and fuel intolerance of other opinions and viewpoints”

For example, the ALA reported the most challenged book of 2020 to be Alec Gino’s George, a book about a transgender girl. Social justice debates ignited by the 2020 murder of George Floyd and ensuing efforts in schools to raise awareness of racism in society have fueled challenges to books like Toni Morrison’s Beloved. In addition to calls for book removal from school curriculums or school and public libraries, legislation is being proposed by politicians targeting “sensitive topics.”

The challenges come from both sides of the political spectrum. According to The New York Times article referenced earlier, the mayor of Ridgeland, Mississippi, recently withheld funding from the Madison County Library System until books containing LGBTQIA+ themes were removed. Others have argued for the removal of classics such as Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird due to its repeated usage of racial slurs and the celebration of “white saviorhood.”

Challenges can also lack consistency within a particular political viewpoint. Conservatives have challenged books used to teach critical race theory while simultaneously lamenting “cancel culture” on account of a publisher’s decision to stop publishing Dr. Seuss’s books with racist imagery.

Today’s book banning, then, unsurprisingly reflects the current divisions permeating American society and brings such divisions and debates into the classroom. The predominant opinion of the Latin community seems opposed to the idea of limiting access to books. In fact, Ms. Metzler could not recall a time when content at Latin had been challenged by students or parents. “I’ve never received a challenge. I don’t think that my colleagues in other divisions have ever told me about a challenge that they have experienced during my 10 years at Latin, and I appreciate our community for that and for valuing a diverse collection that allows us to access all sorts of materials.”

Latin students seem to agree with Ms. Metzler. Maggie said, “I think it is very concerning that students could potentially not have access to books about racial injustice, gender inequality, and other targeted information.”

Sophomore Noa Paige Bremen agreed, saying, “I think high school is an especially formative time where students start to develop their personal opinions and world views, and becoming accustomed to misinformation, one-sided stories, and a tailored experience is very dangerous.”

Of course, Latin’s smaller size and relatively close community may shield the school from having to manage such challenges, and its involved parent community may feel more comfortable with the school’s ability to appropriately introduce and discuss sensitive material. Ms. Metzler believes Latin students are fortunate. “It saddens me to think of students not having access to those materials,” she said. “You learn so much from reading those books.”

Mia Kotler ('25) is thrilled to be one of the Editors-in-Chief for The Forum this year. She is a passionate writer who enjoys expressing her views and...