Holocaust Survivor Speaks at Gathering

Latin’s Jewish Student Connection club (JSC) hosted a gathering on April 8 with Holocaust survivor Eva Paddock in honor of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. Ms. Paddock and her older sister, Milena, escaped their home in a small Czechoslovakian town called Prosek to England through the Kindertransport program, which Sir Nicholas “Nicky” Winton organized. The movement transported primarily Jewish, at-risk children to safety from countries threatened by Nazism—Germany, Poland, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. Before she recounted her story, Ms. Paddock said, “It is my commitment to giving personal witness to our history so that the Holocaust cannot be denied, at least while survivors are still alive to tell our stories.”

On November 9 and 10, 1938, Nazis raided Vienna, killing nearly 100 Jews and sending 30,000 Jewish men to concentration camps while torching synagogues and vandalizing Jewish property, leaving shards of glass from storefronts on the street—hence the name of the event, Kristallnacht, or “Night of Broken Glass.” In response, many Jews organized plans to leave their homes, contacting family and seeking sponsorships and entry visas. Those without the former option fled on foot to the outskirts of Prague, where they stayed in large refugee camps.

Various aid organizations tried to help the Jewish refugees leave the country, but progress was slow. When Nicholas Winton went to one of the camps, he knew that it would be impossible for everyone to escape before the Nazi invasion. With that in mind, 29-year-old Nicholas sat in a hotel, spending numerous hours devising a plan to save the at-risk children who wouldn’t survive otherwise.

On March 15, 1939, the Germans approached Prague, which was approximately two hours away from Ms. Paddock’s hometown of Prosek. Through word-of-mouth, Rudolf heard that he must leave the country immediately and decided to flee to Berlin.

Despite being a three-and-a-half-year-old at the time, Ms. Paddock clearly remembers the Gestapo coming to her home after her father, Rudolf Fleischmeinn, had escaped. Her mother played dumb, yet the officers still brought her to the police station for an interview, leaving the two young girls alone, with the exception of a nurse and maid. Ms. Paddock said of the experience, “I came to recognize that those moments must have been terrifying for a three-and-a-half-year-old because you witness that just by being there.”

Meanwhile, on the train to Berlin, Rudolf met a woman named Ms. Sonia. She was returning home from visiting her grandmother in the Czech countryside and asked Rudolf to keep the window shades closed, confessing that she was using them to conceal illegal fresh produce. Rudolf then revealed his mission: to arrive in Berlin and hopefully board a train toward London the next day. Ms. Sonia offered to house him in her apartment and said she thought her brother could help him get on a train out of Germany. At midnight, Rudolf heard a knock on the door. “In walked a fully-uniformed SS officer,” Ms. Paddock shared. “As my father told the tale, his thoughts then were, Well, I lost that gamble. This is the end of the line for me. But not.”

Mid-morning October 16, 1939, Mr. Schreiber, Ms. Sonia’s brother, accompanied Rudolf to the station, telling Rudolf that they would proceed with one condition: Rudolf must salute and hail Hitler when prompted to. Rudolf complied, successfully boarding the train where Mr. Schreiber instructed the train guard not to permit anyone to enter his train car until he arrived at his destination. Several years later, Rudolf’s friends located Mr. Schreiber, and they maintained a friendship in the following years.

On March 17, Rudolf arrived at the Brussels airport with plenty of cash to pay for a ticket to London, but at the reservations desk the attendant told him they couldn’t accept currency from an enemy territory; Germany had invaded Prague the previous day. In honor of having a newborn baby the day before, Mr. Buganhuud, the man in line behind Ms. Paddock’s father, offered to buy Rudolf’s ticket. The two exchanged business cards, and Rudolf promised to repay him after the war. Years later, Rudolf found Mr. Buganhuud at the same address in Brussels, and they became friends.

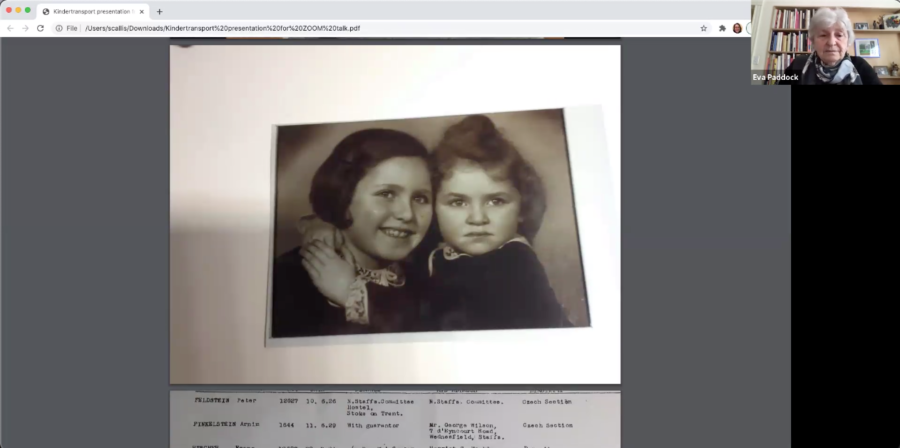

In Prague, Nicholas Winton faced a difficult task: He needed to organize the train to take the children out of Germany and into England, while also finding families to accept each child at the end of their journey and donors who could help pay the 50-pound escrow that the British government required for each child. British families would choose who they would foster from photographs, so when Ms. Paddock’s mother, Sonia, heard of the Kindertransport movement, she joined the hundreds of parents who came to register their children, attaching photos of her daughters to their documents.

Rolland and Florence Radcliffe, an English couple, signed up to take one child, but after seeing the photograph of Milena and Ms. Paddock, they decided to take both, so as not to separate siblings. So the sisters, labeled children numbers 639 and 641, boarded the seventh and last train from Prague to London on July 29, 1939. Another train was supposed to leave on September 1, but war was declared before their departure date, and none of the children who left survived. “In conversations with Nicky over the years, he said that was the most heartbreaking part in his journey of helping these children,” Ms. Paddock explained. “He never really got over that.”

Mr. Radcliffe worked as a secretary for the local Labour Party, and he petitioned the local legislature to help Ms. Paddock’s mother escape Czechoslovakia, a nearly impossible task given German occupation in their home country. The official granted permission and sent documents to Sonia in Prague; she was one of three people who legally entered Britain after the war began, and the German bureaucracy allowed her to leave only because her permission stamp was granted before war was officially declared. Once she exited Germany, however, she couldn’t enter Britain from an enemy territory, so Sonia went to neutral Norway before reaching her destination in May of 1940 with a single earthy-green trunk of belongings.

Ms. Paddock and Milena were among the few Kindertransport children who reunited with their parents. In England, Rudolf and Sonia could no longer pursue their former careers because they didn’t speak English, but they were provided with public housing, furniture, bedding, dishes, toys, and food. The Fleischmeinns settled in England and remained lifelong friends with the Radcliffes.

Nicholas Winton returned home and joined the Royal Air Force of Britain. No one knew of his heroic actions until 1988, when his wife Gretchen inquired about the papers in his office; he kept the files of all 699 children he saved tucked away in a box. Gretchen contacted a newspaper woman who passed Nicholas’s story to a Holocaust reporter who revealed his past in the That’s Life program.

Since then, many survivors visited and got to know him personally, referring to themselves as “Nicky’s children.” After Nicky died in 2015, the remaining 22 Kindertransport survivors boarded a refurbished train from Prague to London in his memory. They also attended his funeral in 2016. “We do still think of ourselves as Nicky’s children,” Ms. Paddock said.

Ms. Paddock pursued a career in teaching before attending university to study English and psychology at 33 years old. “I was always interested in developmental psychology,” she said. “As I look back, I’m sure that my interest was in trying to understand my own history.”

About 20 years ago, Ms. Paddock had her bat mitzvah and started telling her story through poetry, another outlet she used to process her past. She explained, “Writing my poetry was really the beginning of dealing with a lot of that early childhood trauma,” adding that, “I had never thought of myself as being traumatized.” Her poetry beautifully focused on the contradictions of her Kindertransport label:

The label was pure love:

639: this child is mine, child divine,

Save her.

The label was pure evil:

639: this child a Jew, child of spew,

Kill her.

Ms. Paddock’s poetry segued into the reflection of her story in a social context. “I consider the story of my escape, not merely as a corollary to the body of research and documentation of the Czech and of the Kindertransport movements,” she explained. “It is a story of gratitude and wonder and belief in humanity. It is a story of altruism and bravery and selflessness. It is about the people who have graced my life.”

She has since shared her Holocaust experiences several times, including last year at a virtual event for BBYO, an international Jewish youth group, which junior Naomi Altman attended. “I had remembered that I had got to see Ms. Paddock earlier,” Naomi said of when she was planning Latin’s Yom HaShoah event this year. She then reached out to a friend who organized the BBYO event the previous year with Ms. Paddock and got Ms. Paddock’s contact information. With the help of Ms. Callis, Naomi found a gathering time for Ms. Paddock to present to the school and planned the April 6 advisory activities for the Upper School, including a video JSC created to inform the community of the significance of Yom HaShoah.

Ms. Paddock’s presentation touched many students, including junior Izzy Oberman. “Eva’s story meant a lot to me because it reminded me of my family’s personal story about the Holocaust,” she said. “My great-grandmother who survived the Holocaust always advocated to me the importance of remembering it, so to hear Eva do that as a survivor was impactful.”

Senior Claudia Ballen also emphasized the importance of both hearing and maintaining Holocaust survivors’ stories, saying, “Every Jew has some sort of connection to the Holocaust, and educating people on it brings the smallest amount of recognition of the devastation that affected millions of us. The way to ensure we never lose the voices of survivors is to seek ways to hear their stories, in any way available, and then after they’re gone, pass on those stories.”

Senior Nicole Lucas, who started a sticker business to raise money for Holocaust awareness, added, “A lot of people, firstly, deny the Holocaust, and a lot of people believe that anti-Semitism started and ended with the Holocaust and that’s just so far from the truth, so I think that in carrying on Holocaust education, we must just keep telling the stories of those who lived through it because they are not going to be here for much longer. It’s our responsibility to carry it to the next generations because if we don’t, it’s all going to be gone.”

Junior Marissa Isaacs said, “Hearing survivor stories, like Eva Paddock’s, are essential in humanizing the victims of the Holocaust in order to better understand the reality of the war.” She concluded, “By remembering the Holocaust, society must vow to never stay silent during such acts of horror ever again. Listening to survivor stories and sharing their memoirs is the most effective way to ensure that their legacy remains and that their experiences are never forgotten.”

Sign up for Naomi Altman’s project, Messages From the Past: Never Forget, to continue hearing the voices of Holocaust survivors via messages sent out monthy. Text “STORY” to (833) 711-0286 to join.

Marin Creamer ('22) can’t wait to serve her first year as an Editor-In-Chief for The Forum. Writing and editing for the publication has been...

Claudia Ballen • Apr 21, 2021 at 6:21 pm

Great job Marin! So well written!