How Getting Rid of Honors Could Actually Make School Harder

In a time when the quality, nature, and equity of elite institutions are being questioned, Latin must examine its own curriculum.

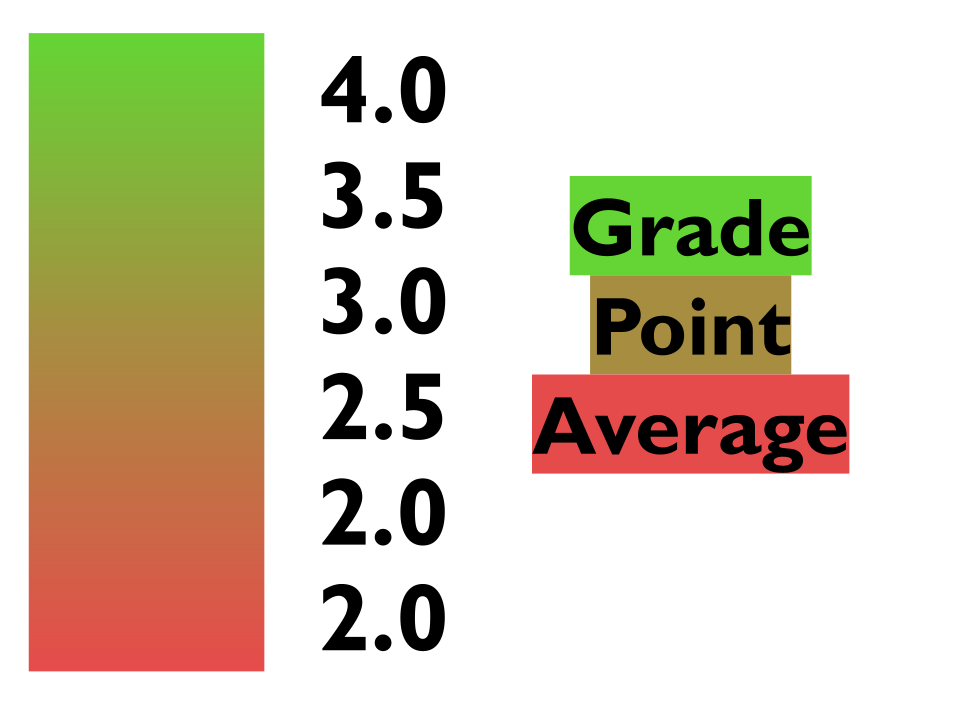

Grade inflation is on the rise, not just at Latin, but nationwide. Distinctions between students based on transcripts are becoming harder and harder to make, especially as the percentage of those taking honors classes rises.

Four out of Latin’s nine freshman physics classes are honors. The same can be said for the school’s sophomore chemistry classes. In junior year biology, honors classes outweigh regular classes five to four. And this large number of honors (compared with non-honors) classes exists in other departments as well.

Honors and AP classes are meant for a few exceptional students. However, this statement is losing its truth with more and more students taking advanced courses. Honors courses are diminishing in value to colleges, and at a prestigious institution such as Latin, they already mean less.

In addition, Cum Laude selection at Latin is much higher than the national average. Cum Laude designates the top 10% of students in the junior class. Upper School history teacher Ingrid Dorer says, “In the last 3-4 years we have had 5-11 juniors with GPAs above 4.0 who could not be inducted into Cum Laude because they were not in the top 10% of their class.” Isn’t a 4.0 GPA supposed to resemble a perfect grade, an exceptional student by any measure? Yet some of these students can’t even qualify to graduate “with praise.” Even senior year, when the top 20% of students are selected, it is tough to qualify. “This year over 20% of the senior class has GPAs over 4.1,” Ms. Dorer said.

These statistics are some of many that show the extent of grade inflation. English teacher James Joyce credits grade inflation to no clear consensus for what elite private schools should be for. “Some see private schools as an investment that promises a return: If the child attends a prestigious high school, it’s the high school’s job to ensure the student will go on to attend a prestigious university afterward,” he said.

Of course, one usual requirement for getting into a selective college is getting good grades in high school. Grade inflation at Latin and numerous other schools minimizes gaps between the best and the worst GPAs, thus creating better transcripts and collegiate prospects … until you look at average grades at a school. Yet, Latin dodges this issue by withholding GPAs from both colleges and, until junior year, the students themselves.

Is there a way to prevent grade inflation while still keeping Latin’s prestigious reputation?

Getting rid of honors classes while still holding everyone to the same rigorous standards ensures a quality education that is fair and equitable to all. It would allow students to have the opportunity to excel but would still make distinctions between students on a transcript. This system would create a more challenging curriculum and greater opportunities for growth. The rigor of a Latin education would stay the same, if not increase.

With Latin offering a generous number of honors classes, why not make every section of a particular course the same level of difficulty? There is essentially a 50/50 split between honors and regular science classes. In U.S. History, there is one more honors class than regular class. With honors already representing a high percentage of students, Latin should teach everyone the same curriculum, which would reduce grade inflation that has reached extreme levels, while pushing everyone to strive for high standards.

Getting rid of honors classes would actually help Latin students in the long run. Students are naturally drawn toward honors classes because of their special distinction on a transcript and how they affect GPAs. Therefore, students pass up more interesting, engaging, and transformative classes. Senior Charlotte O’Toole said, “There are so many opportunities I feel like I missed because I needed to rack up honors and AP classes on my transcript.” If students did not have to make this “sacrifice,” they could learn about what they are most interested in and develop a true passion for a subject or topic, fostering an authentic learning environment that serves teachers and students equally. Charlotte said she would have taken the Finance and Math class or “some really cool history electives” had she not felt so much pressure to take APs instead.

Senior Brendan Meyers said, generally, “I found that this system works great.” He noted that he was able to find a balance between AP classes and other classes, but he also said he recognizes that he “really can’t speak for anyone else’s experience.” Additionally, he said, “I wish I could have thought more about [AP courses] when deciding to take them” as “doing the AP was the logical approach as a senior.”

In addition, students would be able to take more elective classes that better prepare them for college and life after. Max Liss, a sophomore who was new to Latin in ninth grade, credits Latin’s strong English and history programs to their electives. “Compared to other schools, Latin’s English and history programs stand out as the strongest relatively. Latin offers a wide range of English classes focused on different topics for each grade,” he said. “Whereas in most schools, only a few English classes are offered per grade and they vary mostly in rigor, not content. The same holds true for history. But at Latin, there are many options to learn about different regions.”

Both these subjects offer (or will offer) no honors classes, meaning that a school where everyone is held to the same academic standards might be more enticing and produce stronger students.

Lastly, the ethics of choosing honors students are questionable. Should a math test in fifth grade decide the fate of your entire high school math career? Should a kid who speaks a lot in class automatically be put in honors? What about a teacher’s favorite students? Latin essentially admitted to biases and other flaws in honors placement decisions when they decided to change the U.S. history program.

Students have different learning styles, and one teacher may cater better toward one person than another. In addition, who knows how much growth there can be from year to year or how much knowledge a student has on one topic versus another?

Max said, “It is the (sometimes arbitrary seeming) systems put into place in order to put students into level-based classes that can hold students back from their true, unrealized potential.”

A move away from honors will make courses harder if everyone is held to a rigorous standard that challenges us all. Grade inflation would be reduced, if not reversed, and a fairer, more equitable Latin would result. One’s chances of getting into college will not diminish coming from a well-known, prestigious school.

A sixth-grade placement, or any placement for that matter, shouldn’t decide an entire high school track and life beyond.

Akshay Garapati (’23) is excited to be serving his first term as the Sports Editor for The Forum. Previously, he served as the Opinions Editor. Editing...

Gabriel Di Gennaro • Apr 16, 2021 at 3:42 pm

Thanks for this article, Akshay! I particularly appreciate Charlotte’s quote. Y’all are on to something!