Latin’s Least Discussed Identity: Ability

March 1, 2020

While Latin does a great job of talking about identity, ability is a social identifier that is seldom a part of the conversation. Society often stigmatizes ability, which makes it difficult for people with disabilities to share their experiences. Mr. Kanai, who started working at Latin this year, created the Chronic Illness and Disability affinity group to allow members of our community with disabilities to talk about what they are going through and how Latin’s community can be more aware and considerate.

Although Latin works to accommodate chronic illnesses and disabilities, there is still room for improvement. Ms. Sutter, who has worked at Latin for ten years, comments, “We’ve come a long way as an institution when it comes to disabilities.” She explains, when she started working at Latin, “the onus was on me to find a solution to my ‘accommodation issues.’” Rather than supporting her, her employers gave her the responsibility of handling her own illness/disability in addition to the “energy drain” she experiences as she “constantly operates at an altered level of ability.” Fortunately, she has since formed “more of a partnership between [herself] and various offices to come up with solutions together.” She emphasizes the need for “the support and services offered… to be more widely communicated” as many people are “likely unaware that channels exist to ask for and receive accommodations.”

Co-head of the affinity group Caroline Creamer adds, “With an invisible illness, it’s much harder for people to understand how to accommodate the student.” Not only are accommodations not advertised to students, but it is difficult for people providing extra support to empathize when they can’t see what someone is experiencing. Caroline gives an example, “When teachers see a student on crutches, they know exactly what accommodations to provide.” Meanwhile, “due to the fact that most chronic illnesses and disabilities are invisible, it makes them harder to understand,” resulting in a lack of support.

In order to become a more considerate community, Mr. Kanai highlights, “it starts with being mindful that many members of our community are in fact living with and managing chronic conditions every day” and “remembering that we all inhibit radically different bodies.” He offers the statistic, “Forty percent of Americans live with some form of chronic illness.” By understanding that “assuming perfect health from people around us… ultimately harms everyone,” Latin’s community can become more supportive.

Ms. Sutter continues, “illnesses and disabilities that aren’t visible are often simply overlooked and confusion exists regarding why a person who looks healthy needs an accommodation.” The inability for people to look past the fact that a person who appears healthy could have a chronic illness/disability stunts the progress Latin’s community has made to accept individuals faced with adversity.

Mr. Kanai agrees, “There seems to be a lot of growth we can make with awareness and sensitivity among both the student body and faculty.” Although it’s evident that Latin’s support system for people with chronic illnesses and disabilities has improved in the past ten years, Mr. Kanai references how when he hears “students talk about how other students or teachers either don’t believe they’re really sick, or try to minimize the impact of their illness, it tells [him] that we have work to do.”

Ms. Sutter believes the best way to combat insensitivity related to chronic illnesses and disabilities is to have “more conversations around chronic illness and disability.” By doing so, she believes we can “promote greater awareness and understanding of what they are” and realize “chronic illnesses take both a mental and physical toll.” She encourages people to “try getting dressed tomorrow while wearing a pair of gloves” to understand how much harder it is for her to complete daily tasks.

An anonymous student joins in, saying “it can be really frustrating to me… when I can’t get something done because of my illness, and my teachers are disappointed in me.” She mentions how when she is unable to complete an assignment because of her illness she feels “like a failure for something” she “can’t control.”

Additionally, Mr. Kanai highlights the structural elements at Latin that factor into the issue that “access for people who use wheelchairs” is minimal and “the elevator is painfully slow.” In order to become a more inclusive environment to those with disabilities, it’s important to consider how everyday things like walking up the stairs can prove difficult for others.

Ms. Sutter continues, if “you’re good at self-advocacy you’re likely to get more accommodations.” But it’s hard for some students to seek accommodation when they “have a new diagnosis or are still keeping their illness/disability private.”

Because of the stigma created around ability and illnesses, it’s difficult for some to open up about what they’re going through. Caroline shares, “Admitting that you have a disability for the first time can be very scary.” At one point in her life, Caroline thought of her illness as her “biggest secret,” and she feared that people would perceive her “differently because of [her] disease.” She has since learned to become more open about her illness, but she understands that others might not feel ready to share yet, or they may never be. When she was first diagnosed, “[she] never would’ve joined a group where people could have labelled me as someone with a disability.”

“I was always taught to tough things out, which is code for keeping quiet, even if I needed help. Perhaps that’s a male thing,” Mr. Kanai explains.

The anonymous student agrees, saying “For many guys, even ones who go through physical/mental pain, they have a lot of pressure on them to be the binary man.” She believes that male students are limited by the role they believe they have to fill. Continuing, she reveals, “toxic masculinity… is definitely present at Latin.”

Sharing her personal experience with Type One Diabetes, Caroline explains, “Because I’m very vocal about my illness, I received a lot of support for my diabetes.” While Caroline feels that Latin has accommodated her illness well, she’s “more worried for students who are private about their illness or have an illness that” doesn’t have a name. She fears that students who aren’t ready to be vocal about their illness don’t receive the accommodations they need, especially when doctors are yet “to pinpoint which illness a patient has, leaving treatment options slim.” Unfortunately, students who haven’t received a complete diagnosis with an illness are usually “less capable of requesting support due to not having a name for their illness.” Caroline elaborates that typically students without a full diagnosis are “experiencing worse symptoms,” but they don’t have as strong of a support system.

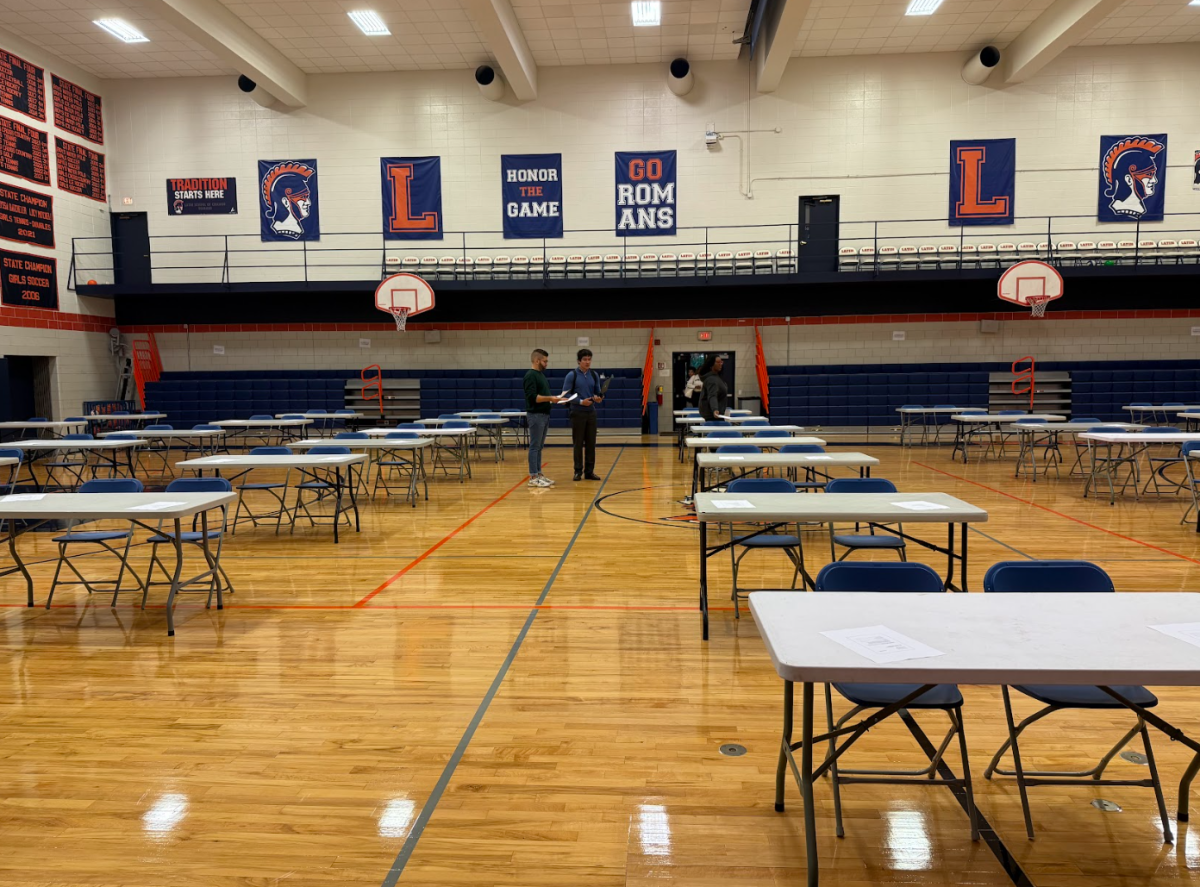

Caroline suggests ways that we can be more mindful of people with chronic illnesses and disabilities which include, “refraining from sneaking in the elevator when you don’t need it, someone with chronic pain might be waiting for it. Skip on making a comment on how ‘testing accommodations are too easy to get’ or that someone ‘only got a good score on the ACT because they had accommodations.’” Caroline stresses how difficult it is for people with chronic illnesses and disabilities to get their accommodations for tests, and it’s “rude no matter what” to make comments about accommodations, especially because it’s “incredibly hurtful to people who had to fight for the right to take a standardized test in a fair and safe environment.” She hopes that our community can become more sensitive despite the “competitive, perfectionist environment at Latin.”

Furthering Caroline’s conversation on Latin’s community that is built on perfectionism, Mr. Kanai says, “I think there is a vulnerability inherent in attending the affinity and that may be a barrier for some students.” He continues, “Perhaps it speaks to the shame and anxiety that people have been made to feel about their illness or disability.” Society engrains the idea of “illness… as a weakness, a mindset we must work to change.”

While Caroline acknowledges that “most people don’t understand what it’s like to have a disability,” she mentions the importance of discussing chronic illnesses and disabilities “in order to make students more aware of how their actions are affecting those with disabilities.” She emphasizes that “nobody expects you to know all the answers, but it’s nice to know that you care” and asks people “to try to be empathetic and accommodating in however you feel is best and not to be afraid to ask how you can best support a friend with disabilities if you don’t know how. I’m always just happy to see that people are putting in the effort to support me. We know that nothing you can say can make the disease go away, so just knowing you’re accepting and supportive is really helpful,” she concludes.

Isabel Coberly • Mar 1, 2020 at 3:22 pm

Marin – This article is so, so important, and very well written! Especially now, when we’re considering the potential effects of coronavirus on the Latin community, we need to be aware of the unintentional effects our comments can have on members of our school. While considering how the most at-risk populations for the virus are elderly and immune-compromised individuals, I’ve heard people say things like, “we don’t even have to worry about coronavirus”—generalizations that can make people battling invisible immune illnesses feel overlooked. Thanks for bringing this issue to Latin’s attention!!