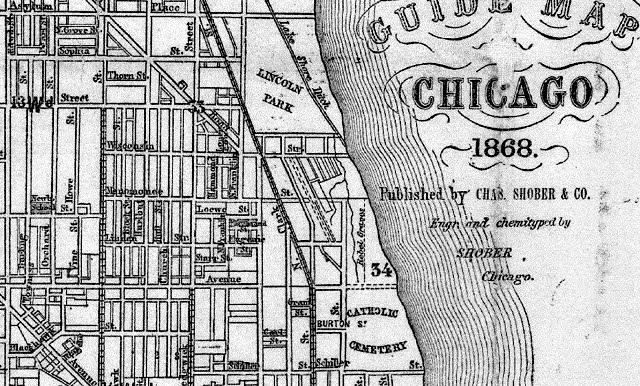

Hailey Hurd Lincoln Park has not always been what we know it as today. We all recognize the grassy fields as home to many of Latin’s sports teams, and where our lower and middle schoolers play every day at recess. We run along the tree-lined paths, rushing to the turf field to watch an exciting game of soccer or field hockey. What many of us don’t know, however, is what lies in this beloved place’s past. According to Northwestern University’s Hidden Truths project by Pamela Bannos, the land that is now Lincoln Park first became a part of Chicago in 1837. Back then, the lake was larger – it went up past where the turf field is now – and Chicago had only been an official city for a few months. The cemetery that developed there over the next few decades was made up of the Catholic cemetery, Chicago’s first Jewish cemetery, the potter’s field (where civil war rebels and prisoners were buried), and a variety of family-owned lots. Soon, however, complaints began to arise from the citizens, and in 1869 the city decided to move the cemetery. This was for a variety of reasons, the first of which was sanitary concerns. People thought that having a cemetery right near their source of drinking water may not be a good idea, and those who lived near it complained that they might get sick from the air. In addition to many citizens wanting a park by the beautiful lake, rural cemeteries were growing in popularity, not only in Chicago but across the country. After many citizens’ letters, the government decided to begin the project. The transition took nearly twenty years, and finally a beautiful park emerged, named after President Lincoln. There are still a few traces of the cemetery left behind, one of which is the Kennison Boulder. David Kennison lived to just over 115 years, and by his 1852 death, the citizens of Chicago were proud to have lived in the same city as him. Kennison was claimed to have been the last surviving member of the Boston Tea Party, and to have fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. It was also believed that he had been a soldier at Fort Dearborn. Most of these claims have been disproved, but the Kennison Boulder placed in his memory serves as a symbol for the pride that Chicago once felt. There is also evidence that some unmarked remains may still lie underneath the park. A Chicago Tribune article from December 10, 1871, about a month after the Great Chicago Fire, describes, “the flames had even made havoc among the dead, burning down the wooden monuments, and shattering stone vaults into fragments.” Because of the unreliable records and destroyed grave markers, the relocation of the cemetery may not have been complete. Over the past century, skeletal remains have been found, including 81 skeletons unearthed in a 1998 excavation. They have also been found during house constructions and sewer repairs in the area, including a 2006 discovery only a few buildings away from the Latin lower school. There is history all around us, not just in the books in the library or a box in an attic, but right in front of our faces. The park we use every day has a hidden past, the buildings we see downtown have hundreds of stories, and we can all find these things if we know where to look.]]>

Categories:

The Hidden History of Lincoln Park

October 1, 2017

0