To be honest, I’m sick of hearing a peer tell me, “I’m starting a club,” or, “If you join my club, I’ll give you a leadership position,” or, “My friend and I are starting a nonprofit-volunteer club.”

What do these claims even mean?

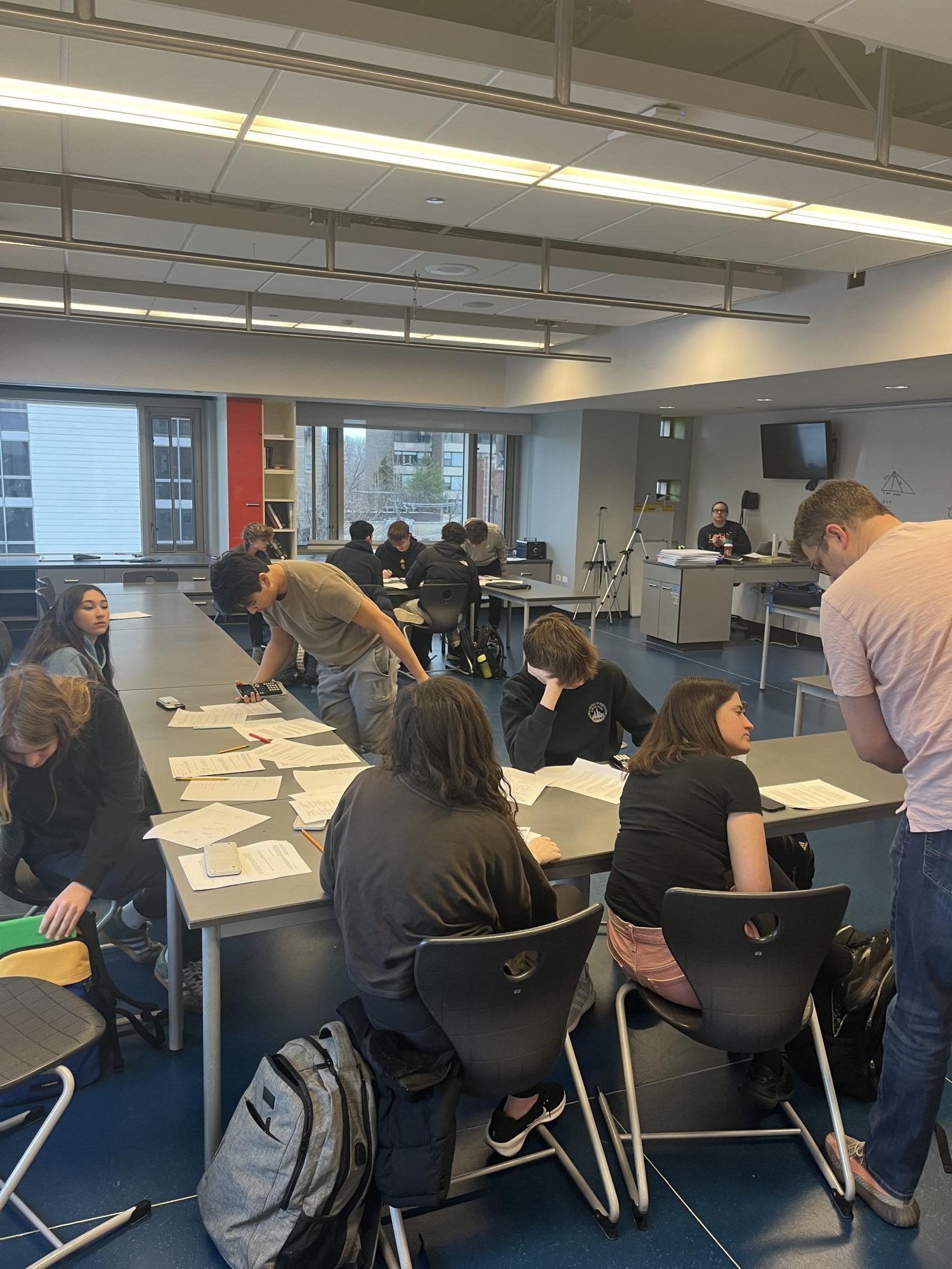

For many students at Latin, extracurricular clubs serve as a space for academic growth, collaboration, and creativity. Latin’s robust club system allows students to start a club anytime, solely with a faculty advisor and a mission statement.

Director of Student Life and faculty manager of student clubs Tim Cronister said, “For me, the mission statement talks about helping students find their individual passions. And so, clubs and service groups, I want to support it.”

Yet, this club-making privilege is excessively abused.

Each fall, I’ve witnessed students start new clubs with captivating names and flashy descriptions. However, come wintertime, those once-alluring clubs have turned inactive, draining student attention and attendance from meaningful clubs. This trend has shifted our once-thriving extracurricular culture into a scene driven by titles instead of community.

Senior and Co-Head of Model Congress Juliette Katz said, “Everybody feels like they have to be the head of something. It’s that pressure that we can’t control—when everyone around you is head of something, and you’re not head, it makes you feel bad.”

This pressure doesn’t just affect those aspiring to leadership roles; it also influences the creation of new clubs. While I do believe that many of Latin’s student-created clubs stem from genuine passion and a desire to fill gaps in extracurricular offerings, many others are born from external pressures. The rise of resume-driven motivations—fueled by college application anxiety and the polished success stories of peers—has created a misconception that founding a club is more valuable than contributing meaningfully to existing ones.

“Students do get caught up in the craze that this admissions world has become, which unfortunately is cutthroat and intense, and it feels that way at Latin,” Assistant Director of College Counseling Alex Zotos said. “In reality, we want students to be pursuing things that actually bring them joy and excitement.”

This college admission focus has led to an influx of clubs created with little substance, diluting the impact of those clubs built on purpose and curiosity.

Over the past two years, I’ve watched clubs with members who dedicate hours to improving their respective organizations lose their member base to a new club that will last three meetings. It’s unfortunate that these hard-at-work, fully student-run clubs have trouble gathering and retaining a following, due to members (and potential members) flocking toward idle, easy-title clubs—contradicting the values our extracurriculars are meant to uphold.

“Our hope is that students are exploring their interests because they are actually intrigued by them and have passions in those areas,” Mr. Zotos said. “We are not in the business of trying to get students to get involved with activities just so they can get into fill-in-the-blank college.”

Nonetheless, this abundance of fleeting clubs at Latin undermines the very purpose of our extracurriculars: to encourage genuine passion and collaboration. Instead of driving students to build community through curiosity, our clubs’ culture is pitting students against one another in a competition for titles and leadership positions.

The result?

A fragmented extracurricular scene where Latin’s impactful, active clubs are struggling to thrive, and students are missing opportunities to further their passions and curiosity.

Even worse, the weakened culture doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. The pressure to attain titles—most of which are meaningless in the long run—will always remain.

To address this problem, we need to create an extracurricular environment where students are more likely to dedicate their efforts to creating a difference in an established, meaningful club rather than wasting their precious time chasing an empty title.

While it is important to acknowledge that some clubs are founded with entrepreneurial intentions, these are exceptions rather than the norm. Still, our students should be drawing inspiration from the group of student-created clubs working with these ambitious intentions. Simply considering if a club will continue to exist and even thrive after the creator has graduated and moved on is a strong litmus test for these scenarios.

“Everybody knows what the established clubs are,” Juliette said. “The clubs that actually get stuff done, they rise to the top and everybody can realize that.”

Juliette spent her four years in high school building her Model Congress club into one of these established, notable clubs.

“My own club—Model Congress—was not established at all when I was a freshman—it was a joke honestly,” she said. “I’ve poured everything I have into that and worked really hard to make a legit application and [getting to] go to out-of-town conferences. As a result, every clubs block, every single kid comes—there are not other kids going other places.”

Unfortunately, the idea of holding a club meeting where all members are present is unimaginable for most club heads. Latin students juggle many different club commitments—a strong testament to all of Latin’s opportunities; however, our schedule is not designed for students to have multiple commitments. The schedule is forcing our student body to make difficult decisions on which clubs to attend, prompting the idea of restructuring the designated clubs block that occurs once in an eight-day cycle.

“I think there's a possibility of doing something where clubs meet on an alternating schedule,” Mr. Cronister said. “What if we took that 40-minute clubs block and split it into two?”

Or, we could implement additional supervision, either through the Upper School administration or student government. “There needs to be more oversight—[club heads] have to make it clear when [they’re] meeting,” Mr. Cronister said. “I think the school should make a commitment to more leadership—the seniors in charge, and the juniors who are taking over, can we make those decisions earlier? Can we get the [club] proposals in [earlier]? Could we have a meeting with all club leaders during community time in April and plan for next year?”

Yet the reality is that for extracurriculars to return to their passion-driven nature, we must first, as a student body, understand that leadership isn’t about holding a flashy title or founding a club for the sake of appearances—it’s about being a genuine, upstanding individual and community member. Too often, students overlook the many ways to lead through small, meaningful actions. By contributing to a club’s success—regardless of your title or position—you are empowering not only your peers but our school as a whole.

“I think students automatically think there's only one way to be a leader in high school, and it has to be with an actual title, like co-head, captain, etc,” Mr. Zotos said. “There are many ways to be a leader in the community, whether that be taking the time after lunch to pick up trash, or helping to support a student in class that needs some help to share their insights.”

Jeff Rastatter • Jan 27, 2025 at 10:35 am

Very well written article and I agree with the sentiment. This trend can continue into professional life. In my industry, medicine, the equivalent would be creation of educational meetings. These meetings are mass produced because of the lure of being among the leadership who created the meeting. The result is there are now so many “educational meetings” that the true education value of on particular meeting is largely diluted. And, many of the meetings have very poor attendance. But they exist partially because of the organizer’s desire to have a leadership position on the résumé. Whereas in high school, the motivation may be polishing the application for college, in academic medicine the motivation is résumé lines and academic promotion We need to refocus on what really matters. In medicine, that is focusing on taking care of patients. Mr. Shah nicely in articulates how high school students can refocus on what really matters.